By: Chad E Cook PT, PhD, FAPTA

What are Mechanisms?

The term “mechanism” reflects the theoretical steps or processes through which an intervention (or some independent variable) unfolds and produces a change in a patient. For example, a cortisone injection for a frozen shoulder works by stopping the release of regional molecules that cause inflammation and stopping the body from the immune response after an injury. Mechanisms studies involve a unique design that is frequently pre-clinical (animal-based or laboratory-based). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines mechanistic studies as designed to understand a biological or behavioral process, the pathophysiology of a disease, or the mechanism of action of an intervention [1].

Chad E Cook PT, PhD, FAPTA

Twitter @chadcookpt

Professor, Department of Orthopaedics, Duke University, Durham, NC. 27516

Competing interests: A portion of Dr. Cook’s salary is funded by the NIH/VA/DoD and the Center of Excellence in Manual and Manipulative Therapy at Duke University.

Author bio(s): Chad Cook is a professor at Duke University, clinical researcher, physical therapist, and professional advocate with a long-term history of clinical care excellence and service. His passions include refining and improving the patient examination process and validating day-to-day physical therapist practice tools. Dr. Cook is a multi-award winner in teaching, research, and service and is a Catherine Worthingham Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association.

What are Mechanisms?

The term “mechanism” reflects the theoretical steps or processes through which an intervention (or some independent variable) unfolds and produces a change in a patient. For example, a cortisone injection for a frozen shoulder works by stopping the release of regional molecules that cause inflammation and stopping the body from the immune response after an injury. Mechanisms studies involve a unique design that is frequently pre-clinical (animal-based or laboratory-based). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines mechanistic studies as designed to understand a biological or behavioral process, the pathophysiology of a disease, or the mechanism of action of an intervention [1].

Proposed orthopaedic manual therapy (OMT) mechanisms include neurophysiological factors [2] including central and peripheral nervous systems, biochemical, biomarkers [3], and physiological factors such as changes in the immune system [4], changes in muscle tone and integrity, and alternations in inflammatory processes [5]. Contextual factors [6] such as social cues, therapeutic alliance, patient expectations, treatment ceremony, pre-cognitive associations, and meaning schema have also been identified as potential OMT mechanisms.

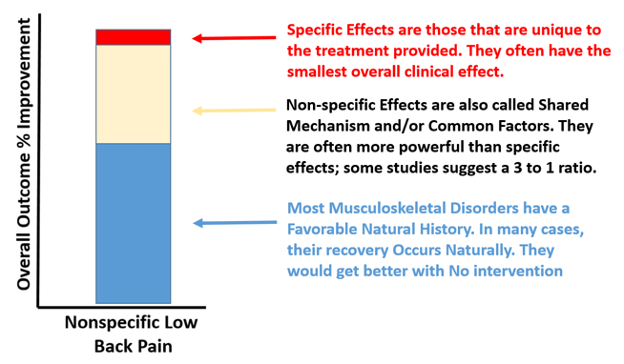

OMT Mechanisms may include specific effects, non-specific effects, and natural history (Figure 1). Specific effects are those that are unique to the treatment applied. For example, a muscle relaxer (drug) provide acts rapidly on the central nervous system as a depressant. It causes a sedative effect that prevents nerves from sending pain signals to one’s higher-order centers. Non-specific effects are symptoms or physiological changes that cannot be explained by the specific mechanisms of the applied treatment. Non-specific mechanisms are sometimes called contextual effects, common factors, or shared mechanisms. The natural history of a condition or disease, refers to the worsening or improvement of the condition in an individual over time that is independent of the treatment provided. Since many musculoskeletal conditions have a favorable natural history, many individuals improve with no treatment.

What are Clinical Outcomes?

Clinical outcomes are usually captured through self-report mechanisms and are a proxy of constructs such as pain, disability, function, or global well-being. Clinical outcomes are influenced by a litany of different factors, including one’s social status, psychological status, and contextual factors, when the outcomes were collected and by whom the outcomes were collected. Clinical outcomes are also influenced by the instrument used and the validity of the tool. NIH defines a clinical trial as a study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes [1].

OMT Mechanisms and Outcomes: It’s Worth Investigating These Concurrently

There are hundreds is studies that have explored specific mechanisms associated with manual therapy procedures. Thousands of studies have explored patient outcomes related to OMT procedures, including hundreds of comparative effectiveness studies (randomized trials). Unfortunately, the extent to which these mechanisms influence clinical outcomes is very poorly studied. This is likely because the design of the two study approaches (mechanisms and clinical outcomes) are markedly different.

Capturing clinical outcomes requires a baseline capture and designated follow-up of patients after they have received care. Capturing mechanisms in manual therapy involves the use of various imaging modalities, quantitative sensory testing, blood draws to blood and serum level cytokines, cortisol, beta-endorphin and opioid responses, spine stiffness devices, electromyography, and many other methods. The capture of these findings would have to occur concordantly with a randomized clinical trial to determine if the presence of mechanisms is different across two comparative treatment groups and whether the mechanisms are associated with the clinical outcomes captured at a later date. This would include many additional costs, an additional time commitment from the patients and the researchers, and very careful oversight. Nonetheless, this is a required next step in OMT research.

References

- National Institutes of Health. NIAID. “What is a mechanistic study?”. Available at: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/what-mechanistic-study#:~:text=NIH%20defines%20mechanistic%20studies%20as,of%20action%20of%20an%20intervention

- Bialosky JE, Beneciuk JM, Bishop MD, Coronado RA, Penza CW, Simon CB, George SZ. Unraveling the Mechanisms of Manual Therapy: Modeling an Approach. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Jan;48(1):8-18. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.7476. Epub 2017 Oct 15. PMID: 29034802.

- Kovanur-Sampath K, Mani R, Cotter J, Gisselman AS, Tumilty S. Changes in biochemical markers following spinal manipulation-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017 Jun;29:120-131. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.04.004. Epub 2017 Apr 5. PMID: 28399479.

- Chow N, Hogg-Johnson S, Mior S, Cancelliere C, Injeyan S, Teodorczyk-Injeyan J, Cassidy JD, Taylor-Vaisey A, Côté P. Assessment of Studies Evaluating Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Infectious Disease and Immune System Outcomes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Apr 1;4(4):e215493. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5493. PMID: 33847753; PMCID: PMC8044731.

- Ruhlen RL, Singh VK, Pazdernik VK, Towns LC, Snider EJ, Sargentini NJ, Degenhardt BF. Changes in rat spinal cord gene expression after inflammatory hyperalgesia of the joint and manual therapy. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014 Oct;114(10):768-76. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2014.151. PMID: 25288712.

- Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(7):403-418. doi:10.1038/nrn3976

Figure 1. Specific, Non-Specific and Natural History Effects.