Spinning for Swaraj

I have read many varying descriptions of myself. Some call me a saint. Others call me a rogue. I am neither the one nor the other. All that I aspire to be—and I hope I have in some measure succeeded in being—is an honest, god-fearing man. But the things I read about myself do not annoy me. Why should they? I have my own philosophy and my work. Every day I spin for a time. While I spin, I think. I think of many things. But always from those thoughts I try to keep out bitterness. Study this spinning-wheel of mine. It would teach you a great deal more than I can—patience, industry, simplicity. This spinning-wheel is for India’s starving millions the symbol of salvation.

—M. K. Gandhi, The Daily Herald, London, 28 September 1931

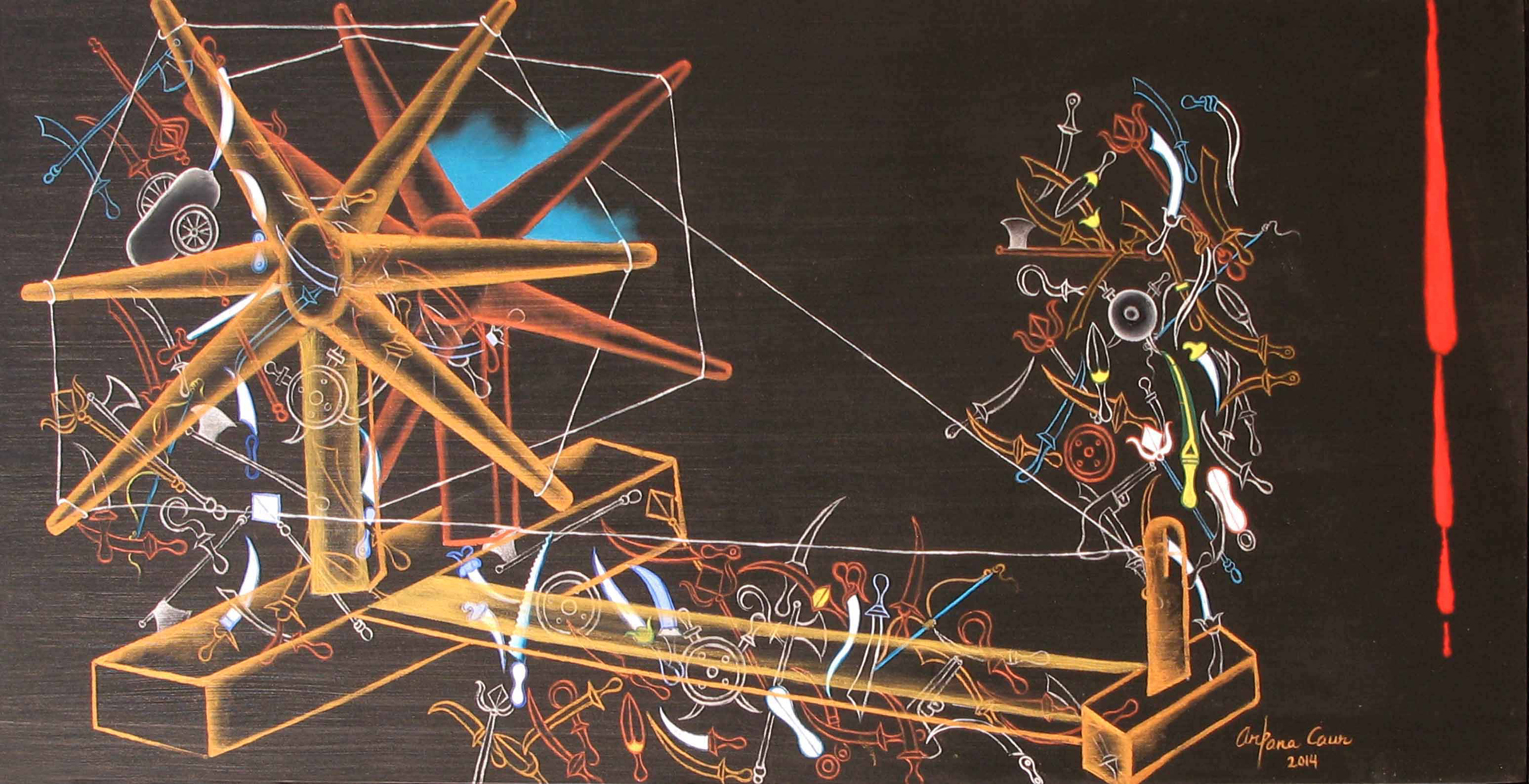

Artistic takes on the Mahatma engaged in spinning range from the serious and somber, as in works by Gandhian Haku Shah (1934–2019) (Fig. 2), to the comical, as in a mass-produced print, revealingly titled Bharatmata ki Godh Mein Mahatma Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi in the lap of Mother India), in which an ageing Gandhi, clad in his usual knee-length dhoti, sits contemplatively on Mother India’s lap in a childlike manner, clutching his spinning wheel as if it were a toy (Fig. 4). So indelible is the association of the spinning wheel today with the figure of the Mahatma that even when Gandhi himself is not present—as in some stunning recent works by New Delhi-based Arpana Caur (b. 1954)—it does not matter. The wheel in fact has become the proxy for the man himself (Fig. 5; Fig. 6; Fig. 7).

In the large and ever-growing scholarship on Gandhi, much has been made about his penchant for spinning. Little attention has been paid, however, to the place of the child which, in the Mahatma’s plans for the wheel, was crucial, if not constitutive. The ideal Gandhian child is a spinning child (Fig. 8; Fig. 9). In turn, with the help of the spinning child, the Mahatma hoped to instill this foundational habit in every Indian household, and across the nation. When the child began to spin and made it a daily habit, the destiny of India itself would be secured. For the sake of the spinning child, Gandhi even invested in the development of “the beautiful takli,” or hand-held spindle, which he insisted was easy to use, took up no space, and produced lots of yarn in virtually no time at all. As early as October 1919, soon after he himself had learned to spin, Gandhi began to call for spinning to be introduced into schools, declaring at various points that if he had his way, he would make it mandatory in the curriculum. In January 1921, he recommended an hour’s spinning every day for the child, but within a matter of weeks, he began to urge that four of the six hours of school time to be devoted to spinning. In April 1922 while in prison, he wrote a primer in Gujarati for elementary school kids which supposed that the intended reader-pupil had already spent a year studying spinning. He also hoped that when it was published, the little book would include “pictures of the spinning wheel.” Spinning took precedence over literary training, and at various points he argued that through the act of spinning, the child could learn history, geography, as well as mathematics. When he formalized his philosophy of nayee taleem (“new education”) in 1937, spinning indeed became foundational to the curriculum.

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Mumbai’s child artists who come to paint in the annual competitions at Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya have certainly not forsaken the charkha, an object that repeatedly appears in their paintings (digital album, 19, 43, 77, 81, 90, 94, 95, 131, 135, 147, etc.). Although their Bapu had insisted that “the only art worth learning is spinning,” the children pay due homage to his passion for the wheel through the art of painting. It is not altogether surprising that they draw and paint him in the company of the spinning wheel—this is after all the iconic image of the Mahatma that they see everywhere thanks to the force of visual culture in iconophilic India.

Nevertheless, they also insert their own imagination—and aspirations and hopes—into the pictures. Thus, young Apurva, a student in Standard IV in S.M. Shetty School, strings up the words “Ham Sab Ek Hain” (“We Are All One”) on the thread spun by her Bapu on his wheel (Fig. 12). Like Apurva, other children make a pitch for adopting native goods and burning foreign manufactures, another pet Gandhian cause (swadeshi). Eighth-grader Dinesh ingeniously replaces the wheel with Gandhi’s own head! (Fig. 13). Like in many a mature artist’s work, another eighth-grader Chetan summons Gandhi into his picture through his proxy, the wheel, a clenched “revolutionary” fist showing the determination to “leave the fad of foreign clothing, appreciate indigenous textiles, make a society free of foreign cloth” (Fig. 14).

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi

23: 122–23; 27: 218–19; 29: 454; 48: 79; 49: 220–21; 85: 141.

Arun Gandhi and Bethany Hedgedus, Grandfather Gandhi. New York: Athaneum Books for Young Children, 2014; “National Week at Sabarmati,” Young India, 5 May 1927, 146; Tridip Suhrud, “Introduction.” In The Diary of Manu Gandhi, 1943–1944, edited and translated by Tridip Suhrud, ix–lxi. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019; and Lisa Trivedi, Clothing Gandhi’s Nation: Homespun and Modern India. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.