Child Art at Mani Bhavan

Mumbai (or Bombay, as it was known in Gandhi’s time) had a special place in the Mahatma’s life. In his own words, “It was the first city of India.” It was also, as the Gandhian philosopher Bhikhu Parekh notes, his chosen karmabhumi (place of action, site of duty). It was the city from where he left in September 1888 for London as a callow 19-year-old, and to which he returned as an accredited barrister, three years later. In April 1893, having failed to make his mark in his homeland, he once again set out from Bombay, this time for Durban in South Africa, returning some twenty years later to a Mahatma’s welcome in early January 1915. He continued to visit the city numerous times over the next few decades until July 1946 to preside over momentous events that punctuated the anti-colonial struggle against British rule. On several of these visits, he went to schools and spoke to children. Here he is on 8 December 1925, addressing the Gujarati National School: “Children, you should realize that you came to this school to learn national service. Most of what you study here should therefore be dedicated to the country.” The patriotic boys and girls of Bombay in turn came out in large numbers to hear their Bapu speak and to participate in various events that he organized. They also corresponded with him. For example, in response to a request from them for a message to commemorate his birthday in 1929, he wrote, “The children who live and study in Bombay ought to know that they are but a drop in the ocean of the crores of children in India. Also, they must realize that a large number of these crores of Indian children are only living skeletons. If the Bombay children look upon them as their own brothers and sisters, what are they going to do for them?” Like the city itself, the children of Bombay too appear to have been charged with a special responsibility in the Gandhian world.

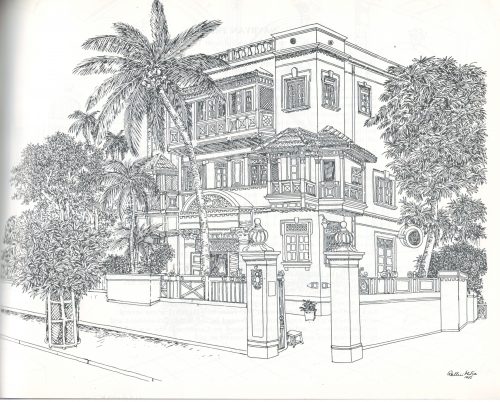

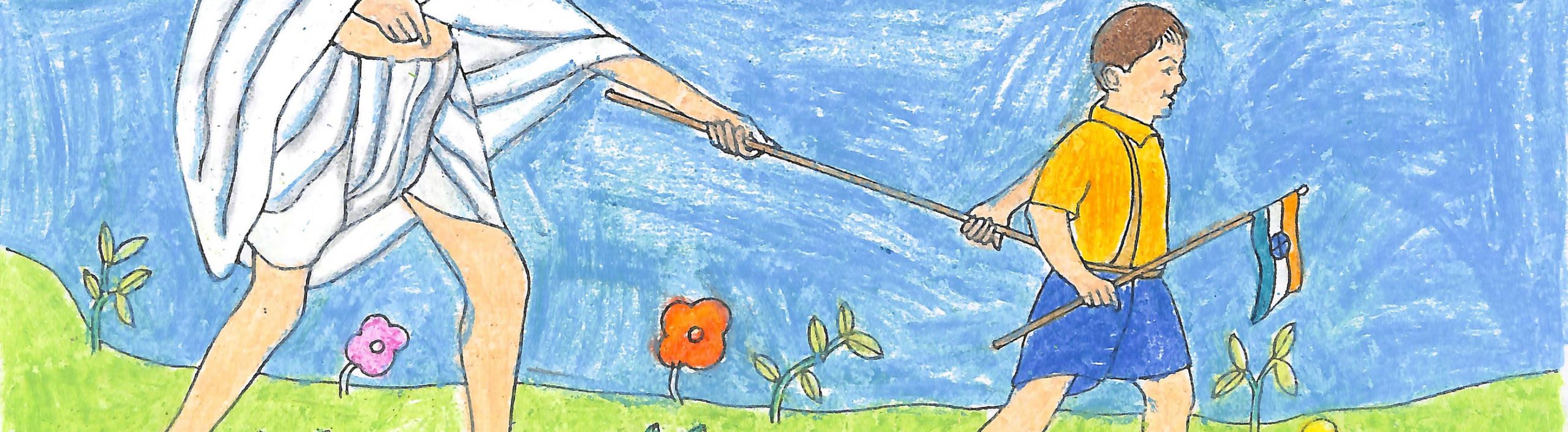

The children respond to the annual call for drawing and painting around specific themes which vary over the years, and are proposed by the office bearers of the Sangrahalaya and the Nidhi who also choose each year the best of the works that are honored in an awards ceremony. Each child is given an hour to complete the work on paper, typically using color crayons and poster paint. Many themes are playful, even cheeky (“Gandhiji and his goat,” “Gandhiji riding a bicycle,” or “Gandhiji playing cricket”), but several are quite serious (“Gandhiji as a prisoner,” “Gandhiji, the victim of the color bar,” and “environmental pollution”). Among the favorites are “Gandhiji and his pocket watch,” “Gandhiji is writing,” and “Be the change you want.” The children have also been invited to paint “Gandhi of their imagination,” Gandhi walking on the seashore or meditating, and even the martyrdom of the Mahatma. A special place in these paintings has been accorded to Kasturba, Gandhi’s wife and companion from the time they were both 13: she makes an appearance in many works, even when she is not connected to the theme. In 2007, the children were invited to paint on the subject, “I saw Gandhiji in Mani Bhavan” (digital album, 11). Every now and then and of their own accord, the children paint Mani Bhavan in the background, so indelibly connected are the Mahatma and the Museum in the popular imagination (Fig. 5; Fig. 6).

There is virtually no scholarship on child art in modern India, and rarely are children’s drawings or paintings saved or deemed worthy of preservation. This is also what makes the archive of children’s paintings of Gandhi in Mani Bhavan such a precious resource. What Diane Mavers has observed about children’s artwork more generally, holds true for these paintings, “The unremarkable is actually remarkable…much of [it] is apparently unexceptional: a swift drawing dashed off in a few moments, a routine classroom exercise…, copying from the class whiteboard. Yet, viewed through a certain lens, what children do as a matter of course becomes surprising. Ordinariness masks richness and complexity, routine features that pass by largely unnoticed are not at all trivial, and commonplace ‘errors,’ even if not overlooked, are replete with meaningfulness. What might appear mundane, effortless, mistaken, even uninteresting, turns out to be intriguing.”

Like many a professional artist, the child as well frequently turns to photographs of the Mahatma—the most photographed Indian of his time and since—using pencil and poster color to reanimate an inherited black and white image. For example, over the course of three years from 2013 to 2015, young Ambuj, a student of National Sarvodaya High School, produced a series of award-winning sketches, each adapted from well-known photographs, each with an interesting history in the life story of the father of the nation (Fig. 7; Fig. 8; Fig. 9). Ambuj’s reworking in Fig. 8 of a photograph by William Shirer (also made into a poster) even reminds us that Gandhi was ambidextrous, and sometimes wrote with his left hand when his right got tired!

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Similarly, American photographer Margaret Bourke-White’s much-circulated photograph from March 1946 of the Mahatma absorbed in reading, his spinning wheel in the foreground, is recalled in a pencil sketch by Rahul, a teenager studying in I. B. Patel Vidyalaya in class X (Fig.10).

Gandhi famously ignored world-renowned artists who sought him out to draw, paint, photograph, or sculpt him. And yet, he had the kindest of words when a child sent him a drawing or painting, noting on one occasion that he was delighted to receive “funny drawings,” and at another time even writing from prison to young Satyavati in 1930, “The sketch of a flower-pot with flowers standing upright is so good that the flowers seem to emit fragrance.” In a similar spirit, I too have chosen in this project to honor the art works archived in Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya, as I draw on them as a historian to look anew at the most famous Indian of his time, and since.

Select References

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi 26: 384; 29: 303; 41: 414; 45: 45; 48: 490; and 50: 411.

K. Gopalswami, Gandhi and Bombay. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1969; Diane Mavers, Children’s Drawing and Writing: The Remarkable in the Unremarkable. New York: Routledge, 2011; and Usha Thakkar and Sandhya Mehta, Gandhi in Bombay: Towards Swaraj. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2017.