Pinching Salt

In 2008 with the financial backing of the Aditya Birla industrial group, Crossfire Films released a short video titled Namrata ke Saagar, “Ocean of Humility,” directed by George M. Thomas. As we hear the singing of a hymn attributed to Gandhi in the immortal voice of Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, we are treated to a lovely imaginative and imaginary encounter between a saintly Mahatma and two mischievous village boys involving his gold waist-watch—one of the few possessions he held on to even as he shed his dependence on worldly goods. The plot line of the short video is this: Somewhere along the way as he walks across the Gujarat countryside on his way to make salt (illegally) on the Dandi seashore (12 March–5 April 1930), Gandhi misplaces his precious watch which falls into the hands of the two young boys who are compelled by their shocked mother to return it to him when they finally get to meet him in person. In exchange for the return of his watch, he returns one of their glass marbles which had come into his possession. Waist-watch and glass marbles having been so exchanged, Bapu and the children play a little, and he then blesses them. The brief encounter between the Mahatma and the children ends with one of the boys gifting his entire cache of precious marbles to the Gandhian cause.

Notwithstanding the fact that the short film might have erred in its misuse of one of the words in Gandhi’s hymn for its title, Namrata ke Saagar is important for the attention it gives to the child in relation to the Mahatma in the course of what was perhaps his moment of greatest nationalist triumph and global visibility, the Dandi Satyagraha or Salt March. Some years after the event, Gandhi wrote on 29 November 1933 to Manu and Mavo, the two young sons of his associate and translator Valji Desai, “I always enjoyed moving around with children, especially on foot as during the Dandi March.” And yet, in the vast scholarship on this event, there is virtually no consideration given to children. In the days leading up to the start of his historic 241-mile march from his Sabarmati Ashram to the Dandi seashore, Gandhi himself vacillated on this matter (despite his later pronouncement to young Manu and Mavo). A week before he set out, at a prayer meeting on 5 March, he declared, “In the coming struggle, even children might get killed. Knowing this, if we take children with us it would be sheer folly.” Women too were explicitly prohibited from joining the march. At the end of the first day on reaching Aslali, he spoke to a crowd of about 4,000 (including about 500 women), and once again assumed that only men should be called upon “to violate the salt tax.”

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Mumbai, 2014

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

We learn both from oral histories and the memoir of Narayan Desai who grew up in Sabarmati Ashram (and whom Bapu was fond of addressing as Bablo) that child residents clamored to be selected to march with him, but to no avail: in the band of 78 male marchers whom Gandhi handpicked, there were a handful of older teens, the youngest, 16-year-old Vithalbhai Thakkar. This is in contrast to an earlier march—his first such—in November 1913 in South Africa when Gandhi’s so-called army of peace included 57 children, some of them apparently infants in the arms of their mothers who set out with the intention of walking some 20 miles for eight days in fairly hostile territory. Within a few days of being on the road to Dandi, however, Gandhi changed his mind, likely because so many women, many with their children in tow, showed up to greet him and cheer him on his historic march. On 15 March on reaching the village of Dabhan, he announced, “Ours is a holy war. It is a non-violent struggle. Even women and children can take part in it.” On 26 March, on reaching Broach (Bharuch), he was “seeking help on bended knees” from the old and the young alike to join his cause, and particularly delighted that so many “little girls” were writing “insistent letters…demanding enlistment.” The day after, in the village of Mangarol, the future “salt thief” let it be known, “Even children should openly steal salt.”

Image courtesy the artist’s family

After daybreak on 6 April 1930, when he reached down to the wet earth and picked up a pinch of salt, becoming “a law breaker” in the eyes of the state, Gandhi called upon all Indians, including children, to follow his example. A week later he declared that whole villages in Gujarat “have set out to offer civil disobedience. Men, women and children are taking part in it.” By 27 April 1930, he was proud to note in “A Message to America” published in The Sunday Times, that across the country, “Hundreds of thousands of people, including women or children from many villages, have participated in the open manufacture and sale of contraband salt” (Fig. 7). In a message in Navajivan on 4 May, he observed that a seven-year-old Parsi girl had sent money for the cause, and that the children of Vapi had collected Rs 300. “One little girl among them asked whether she might join the struggle. When such innocent children show a desire for service, who can help believing that they are prompted by God? I see no insincerity in these girls.” He appears to have been particularly tickled by the initiative taken by some children—most likely led by Indira Nehru, a future prime minister—to form the “monkey brigade,” or Vanar Sena. Renouncing their toys and kites, these young “soldiers of swaraj,” as he christened them, some of them only six years old, were further proof that his was a battle of Right against Might.

From the album Collections of Photographs of Old Congress Party. The Alkazi Collection of Photography, ACP: 98.77.0002 (24)

From the album Collections of Photographs of Old Congress Party. The Alkazi Collection of Photography, ACP: 98.77.0002 (25)

From the album Collections of Photographs of Old Congress Party. The Alkazi Collection of Photography, ACP: 98.77.0002 (218)

Bombay was a hotspot of civil disobedience with the “disobedient” men, women, with several children heeding the Mahatma’s call to make salt and break the salt laws. Photographs preserved in an album titled Collections of Photographs of Old Congress Party in the Alkazi Collection of Photography in New Delhi show young boys and girls out on the streets, carrying banners, and waving flags (Fig 8; Fig. 9; Fig. 10). Oral histories and historical accounts suggest that children sang songs praising nationalist leaders, witnessed the boycott of British goods, took up spinning, and of course joined their mothers who merrily went about making and selling contraband salt.

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

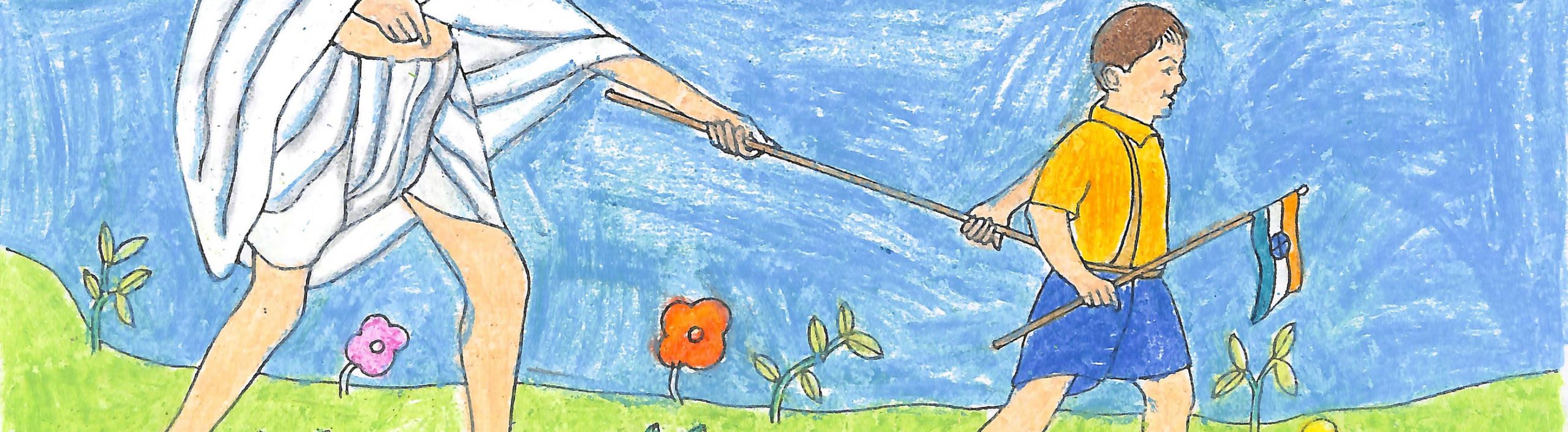

Over the years that the painting competition has been conducted in Mumbai’s Mani Bhavan, Gandhi’s historic march to Dandi and the Salt Satyagraha has been the subject of numerous paintings, several of the award-winning ones reproduced on this website and in the digital album, 100–119). These child artists have been inundated with images of the Salt March that circulate in India’s visual culture, from public statuary to postage stamps to comic book illustrations and posters, not to mention high art. At one level, therefore, there are few surprises in the children’s representations of this historic event. Nonetheless, some original and innovative sentiments enter the picture. Sometimes, this takes the form of inscriptions that the child adds to the painting. “If you want something which you never had, you have to do something, which you never did” (digital album, 101); “inquilab zindabad,” “long live revolution!” (digital album, 105), “Bapu, you lifted a pinch of salt, with that the British Raj was finished” (digital album, 108), and my favorite, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, THEN YOU WON” (digital album, 116). At least one of the child artists invited to Mani Bhavan in 2014, Sanskar, might have seen Namrata ke Saagar, for in his painting, as in the film, he has two young boys perched on a tree limb bearing witness to Gandhi and a loyal group of followers marching by, one of them bearing a tanpura, a couple others carrying the Indian tricolor (digital album, 113).

Consider also ninth-grader Vedika of St Paul’s Convent who contrasts Gandhi’s non-violent picking up of salt on the seashore with the violent acts in the background: in her mind, there is no doubt which is the more effective way to “independence” (Fig. 13).

Young Jigisha, fifth-standard student of Udayachal, even has little child-like figures join their Bapu in his “empire shaking” adventures with that most mundane of materials, salt (Fig. 14). With such painterly efforts, these young artists insert this most historic of Gandhian marches into children’s history.

Select References

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi 43: 13, 63, 79, 126, 142, 334, 385; 45: 349; 56: 293.

Narayan Desai, Bliss Was It to Be Young with Gandhi: Childhood Reminiscences. Edited by Mark Shepherd. Translated by Bhal Malji. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1988; and Thomas Weber, On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi’s March to Dandi. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India, 1997.