Bapu Behind Bars

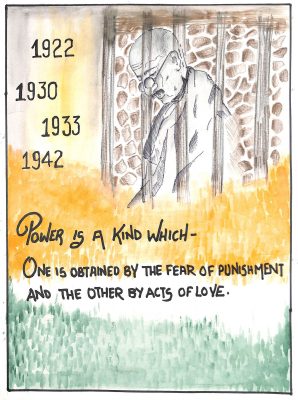

Between 10 January 1908 when he was first thrown into prison, and 6 May 1944, the date of his last release, it is estimated that Gandhi spent a total of 2,338 days in jail in colonial South Africa or India, give or take some ten days. From around 1908 when he was first incarcerated in Johannesburg as his life and career increasingly turned towards disobedience, Gandhi began to characterize going to prison (or “gaol”) as a high “prestige” activity for all self-respecting Indians. It was nothing to be ashamed of, indeed, the very opposite. “The gaol then be will like a palace to them.” Over the years, he further elaborated on this theme, declaring in an article published in Young India in August 1921, “If only our men and women welcome jails as health resorts, we will cease to worry about the dear ones put in jails which our countrymen in South Africa used to nickname His Majesty’s Hotels.” A few months later he wrote in a similar vein on 26 January 1922, recalling his time in a South African prison, “I learnt most when I suffered most. It was the time of the fattest harvest. Whilst the suffering lasted, it was difficult to bear. But it is now one of the richest treasures in life’s memory. We have today converted the jails into heavens of refuge for liberty-loving men. They can be easily turned into abodes for attaining nirvana.” By 1930, when he wrote From Yeravda Mandir, he even likened his (temporary) prison cell to a temple (mandir), a house of god(s) where one seeks sanctuary, solace, and salvation.

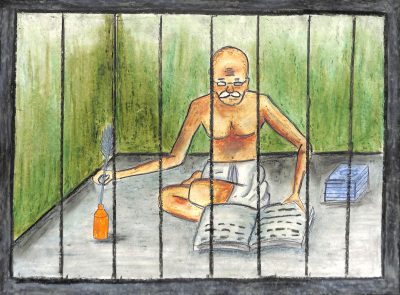

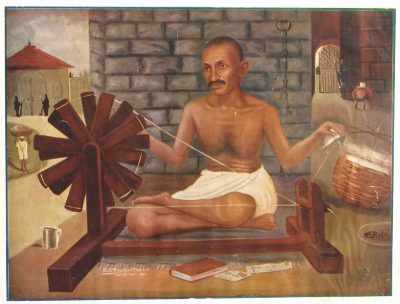

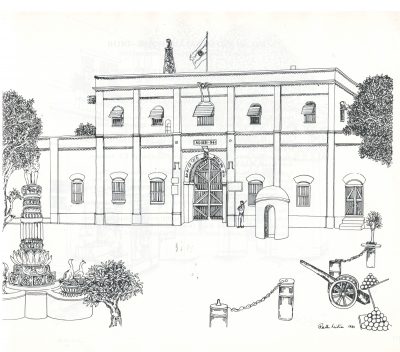

Of course, such a characterization came to be also possible because by the 1920s, M.K. Gandhi might well have been the British Empire’s most famous political prisoner: each time he was thrown (often reluctantly and as a last resort) into jail, the colonial state worried about his health and wellbeing, especially as he also had a tendency to go on grueling fasts while he was behind bars. So much so that in August 1942, the British “jailed” him in a palace, literally. As a political prisoner, he received kid-glove treatment. Nevertheless, there were deprivations he suffered, including being cut off from family, friends, and the communities that sustained his political-ethical life. He was arbitrarily prohibited from writing letters to some individuals or receiving certain newspapers which, for someone who was so media-attuned, must have been a torture of sorts. And of course, a life of constant mobility and travel was brought to a complete halt. Nevertheless, being Gandhi, he also put the hundreds of days he spent behind bars to “constructive” use, writing, reading, and spinning. (In March 1922, on his first full day in Yeravda Jail at the commencement of a six-year prison term, he went on a fast on being deprived of his spinning wheel. The prison authorities relented within 24 hours!)

Prison life gave Gandhi a chance to intensify his connections with a special constituency: the children of India (and even of the world), and particularly the boys and girls of his ashram(s). He kept up a steady stream of correspondence with them, writing to them and responding to their letters, frequently in some detail. He even responded to letters from children in England—both those whom he had met in 1931, and the children of his followers there. His numerous letters to the ashram children are filled with words of advice and counsel, but also admonitions (over their bad handwriting, their quarrels and escapades which were reported to him, their failure to spin their daily quota, and even their forgetting to write to him!). Some of these letters have a collective address (“Dear boys and girls”), others are highly individualized and caring communications. Given the chance to receive visitors, he often asked to see the children of the ashram, listing their names and sometimes their identity. Thus, a letter dated 26 April 1923 to the superintendent of Yeravda Central Prison requests visitation rights for “Lakshmi Dudabhai Gandhi, a young suppressed classes girl, seven years old, who has been brought up and adopted by me.” Along with young Lakshmi, he also asked to see grandniece Radha Maganlal Gandhi, 14 years old, grandnephew Krishnadas Chhaganlal Gandhi, “about 12 years old,” and other ashram girl children such as Moti Lakshmidas, “about 15 years old,” and Laxmi Lakshmidas, aged 13. Similarly, a letter of 21 April 1932 to Colonel Doyle, Inspector General of Prisons of the Bombay Presidency, names a very special child who he expressed a desire to see: “Indira Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter, 14 years old and studying in Mr. Vakil’s School in Poona.” In turn, young Indira wrote to her father—Gandhi’s political heir—in September of that year about her visit with Bapu in jail, giving a detailed report of the breaking of his “fast unto death” on 26 September. “I think it is very wonderful, how one man can do such a lot. Up until now I had thought Bapu a great man, no doubt, but I had somehow never thought him capable of this. So, this fast has made a great impression me and has taught me a great lesson.”

One child who accompanied her Bapu into jail—or more correctly, was summoned to join him to help with the care of the ailing Kasturba (“Ba”)—was his grandniece Mridula Jaisukhlal Gandhi (“Manu”) whose daily diary has been recently translated and published by Tridip Suhrud. Manu began prison life as a 14-year-old, jailed in Nagpur goal for some nine months with some older Gandhian women in the wake of the Quit India movement in 1942. She was then transferred in March 1943 to the plush Aga Khan Palace where the Mahatma was confined for almost two years. Her diary entries are a revelation of what it meant to be a young prisoner—and to be one in the company of Bapu and Ba. They show how Gandhi and his large entourage continued to follow the strict routines of ashram life and diet, albeit being “in prison” and in the palatial environs of the Aga Khan Palace. Particularly candid are Manu’s experiences with nursing Kasturba in her last days, and her detailed descriptions of Ba’s death and cremation are both moving and harrowing. Despite Manu’s share of trials and tribulations, one diary entry dated to 4 June 1943 has a confession, “I like it here very much. I do not think that even once I have felt that I am in confinement or that I am forced to live in a jail.”

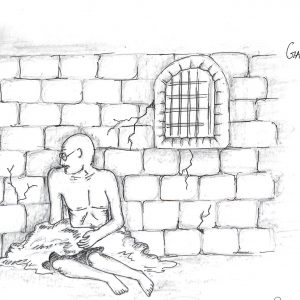

From Rathin Mitra, Gandhi: An Artist’s Impression: Text & Drawings. New Delhi: All India Congress Committee (I), 1985

From Rathin Mitra, Gandhi: An Artist’s Impression: Text & Drawings. New Delhi: All India Congress Committee (I), 1985

From Rathin Mitra, Gandhi: An Artist’s Impression: Text & Drawings. New Delhi: All India Congress Committee (I), 1985

Today, the places where Gandhi was interred in India—Sabarmati Jail, Yeravda Jail, and the Aga Khan Palace—are all major heritage sites on the Gandhi memorial tour, and which one can even visit virtually. Professional and gallery artists have made the Mahatma’s life in prison a subject of aesthetic contemplation (Fig. 7; Fig. 8; Fig. 9; Fig. 10; Fig. 11), as indeed have the child artists at Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya whose imaginative visualizations of Bapu’s life behind bars may be seen both in the digital album, 122–35 and on this page. The children see him as filled with power even when incarcerated (Fig. 1), as absorbed in tasks such as spinning (Fig. 3), writing and reading (Fig. 5), including books such as his most important work Hind Swaraj (Fig. 6), oblivious to the presence of guards (Fig. 4), and meditating (Fig. 13). So indelibly have Gandhi and prison become associated even in the mind of the child that when young Swati was invited to paint “Gandhiji in My Imagination,” she placed him behind bars, with a dove hovering over him, holding out the scales of justice (Fig. 12).

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi 5: 414; 8: 442; 20: 466; 22: 245; 23:

165; 49: 336.

M. K. Gandhi, My Early Life (1869–1914), Arranged and Edited by Mahadev

Desai. Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1932.

Prabhudas Gandhi, My Childhood with Gandhiji: Foreword by H.S.L. Polak. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press, 1957; Sonia Gandhi, ed. Freedom’s Daughter: Letters between Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, 1922–1939. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989; and Tridip Suhrud, ed. and trans., The Diary of Manu Gandhi, 1943–1944. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019.