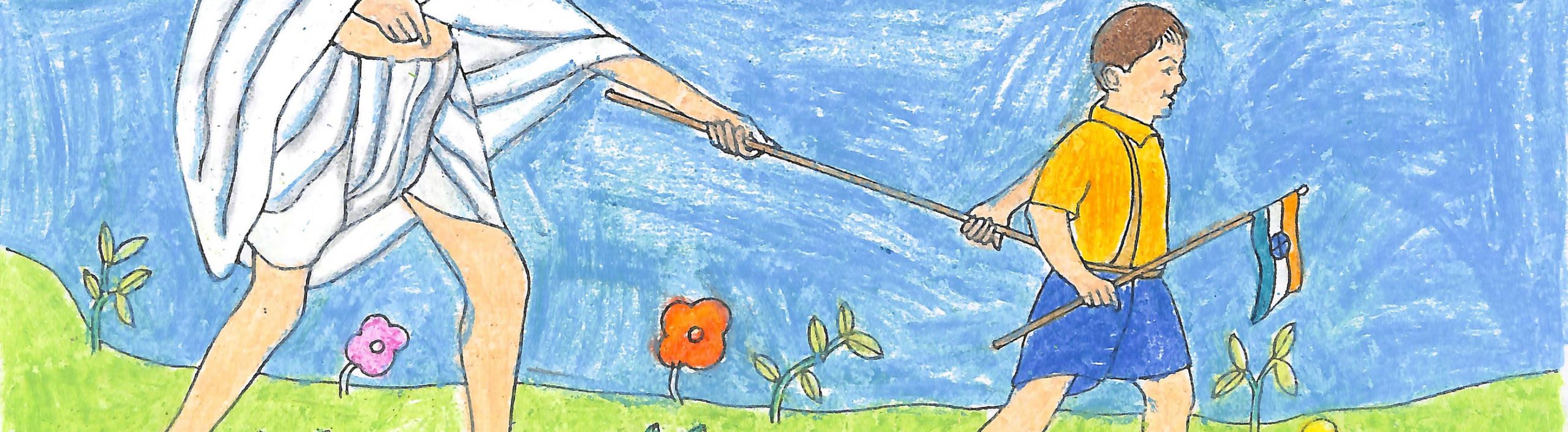

The Child in the Making of the Father of the nation

This project underscores the importance of the child in the making of the father

of the nation. Of the several titles conferred upon him, the one that Mohandas

Karamchand Gandhi embraced wholeheartedly was bapu, “father.” In the

early years of the 20th century, he came to be widely referred to as such, as he

increasingly took up the cause of his fellow Indians against a racist colonial

state in South

Africa. By his own admission, Gandhi felt he had failed as a father of his

own four sons, and was even quite ambivalent about fatherhood, preferring at

times to see himself as “mother.” Increasingly though, after 1915, he referred

to himself as Bapu when he signed off on routine letters to family, followers,

and friends: the phrase “Blessings from Bapu” recurs across his voluminous

correspondence, even when he wrote to adult men and women.

Who then was a child in the eyes of Bapu? As is typical of Gandhi, in this

regard as well, there was some inconsistency. At a very fundamental level,

anyone younger than 16 years of age was a child in his eyes. “According to our

shastras [traditional precepts], a child should be lovingly reared for five

years, should be disciplined for ten years—‘disciplined’ not with physical

punishment but with instruction and persuasion—and a son of sixteen should be

regarded as a friend.” All the same, every now and then, Gandhi also suggested

that one crossed “the age of innocence” at age 12, and responsibilities began to

mount after. By 1937 when he began to promote what came to be called nayee

taleem or new education, schools opened under its aegis typically were

limited to those under 14. However, Gandhi also used words like “child,”

“children,” “boy,” and “girl” (and their equivalents in Gujarati and Hindi)

capaciously, especially as he himself got older, to refer to close and intimate

adult followers. Even those who were not Indian were frequently referred to as

such, a case in point being his Danish devotee Esther Faering Menon, letters to

whom invariably began, “My dear child.” At this level, because he was deemed

father of the nation, all citizens of India were by definition his children.

Such a broad usage was also in keeping with his sense that all human beings are

children in the eyes of the deity. He may have been Bapu to millions, but he

himself was also a child, not just of God but of Mother India:

I cling to India like a child to its mother’s breast, because I feel that

she gives me the spiritual nourishment I need. She has the environment that

responds to my highest aspirations. When that faith is gone, I shall feel like

an orphan without hope of ever finding a guardian.

This project is specifically focused however on children—and child artists—who

are less than 16 years of age and what they made of their Bapu, and what he

thought about them. To a large extent, the Mahatma’s evolving views on children

were generic: he considered them “pure” and “innocent,” and a “joy” to be

around. As did so many others, he saw the future of India in its children and

youth. Like many an adult, he also found them less complicated and easier to

bend to his will.

At the same time, more so than other male leaders of his time, Gandhi spent a

lot of time thinking about and addressing issues specific to childhood from

toilet training to budding sexuality, writing extensively to children and

speaking to them, spending hours in their company, and openly professing the

importance of learning from them, his letters and speeches replete with specific

examples and instances of such lessons. His residences were filled with children of kin and

followers alike. Several of his political-ethical projects—be they the awakening

to racial justice in South Africa, or the use of fasting as a practice of

persuasion—were on account of children. His speeches and writings frequently

invoked children of Hindu mythology and literature such as Prahlad and Shravan

as exemplars for the adults of his generation. Virtues he associated with

children—their simplicity, candor, even sense of mischief and play—were held out

to adults to imitate. “We have all to aspire after being childlike. We cannot

become children, because that is impossible. But we can all become like

children.” When he was around children, as many a contemporary noticed, he

became like a child himself, readily and willingly taking on their persona.

On the other hand, and sometimes in the same breath, he would scold adult

followers for being childish, or for behaving like children. While he held

children out as exemplary, he still sought to transform them into the ideal

child of his vision. In a moment of extreme thought—to which he was not

infrequently prone—he even declared that if it was left to him, there would be

no children brought into this world.

Over the decades, India’s children have been bombarded with books about their Bapu, including some beautifully illustrated by well-known artists. Yet few who have really explored what Gandhi said, wrote, and thought about the child, and even fewer have asked what the child made of him, whether in words or images. This project takes on these matters in order to emphasize the child’s constitutive place in the making of the man we hail as Mahatma.

Select References

M.K. Gandhi, India of My Dreams. Edited by R.K. Prabhu. Bombay: Hind Kitab, 1947, 13.

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi

9: 205; 18: 329; 55: 209; 61: 394.M.K. Gandhi, India of My Dreams. Edited by R.K. Prabhu. Bombay: Hind Kitab, 1947, 13.