Visualizing the Child with Gandhi

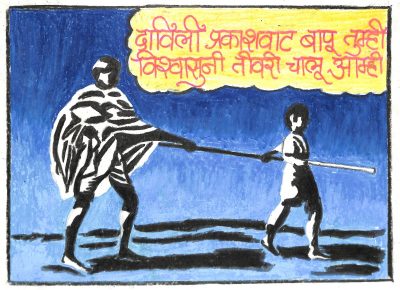

As we know from children’s memoirs of growing up with Gandhi, he was wont to take his morning and evening walks in their company (digital album, 14, 15, 26, 27). As Narayan Desai (or “Bablo,” as Bapu called him) recalled in later life:

My earliest memories of Bapu are intertwined with those of Sabarmati Prison. Bapu would go for a walk each morning and evening. He would put his hands on the shoulders of those either side. These companions would then be Bapu’s “walking sticks.” We children were always given top choice for this job. Whether his human walking sticks were really any help to him, perhaps only Bapu could say. But as for us, being chosen always made us swell with pride. In fact, in our eagerness to be chosen, Bapu’s “sticks” would sometimes clash together.

Image courtesy the artist

From Neville Tuli, A Historical Epic: India in the Making, 1757–1950: From Surrender to Revolt, Swaraj to Responsibility. Mumbai: Osian’s, 2002

Professional artists have also repurposed another well-known photograph from 1944 of Gandhi nuzzling baby Nandini who happily clutches a banana. Nandini was the motherless niece of Gandhi’s devoted doctor Sushila Nayyar and her brother Pyarelal Nayyar who was his loyal secretary (and biographer). The Mahatma was much taken with the infant, even holding up her happy disposition as an example to one of his disgruntled older followers, “Be cheerful like Nandini,” he wrote at one point. Young Manthan, a student studying in Standard VII in I.E.S. Modern School, recreates this cheerful encounter between Bapu and the banana-carrying baby in his painting titled Loving Rastrapita [Loving Father of the Nation] (Fig. 7). But he is not the only one to do so. The Tamil artist K.M. Adimoolam (1938–2008) who grew up admiring Gandhi repurposed the photograph in 1969 (Fig. 8), as did Jaipur-based Gopal Swami Khetanchi (b. 1958) more recently in his Innocence (Fig. 9).

Image courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

From Between the Lines: Drawings by K.M. Adimoolam between 1962 and 1996. Chennai: Value Arts Foundation, 1997

Indeed, children appear frequently in Khetanchi’s many paintings from his 2010 series Gandhigiri, including one with the suggestive title, Children Are the Father of the Nation, Not Me (Fig. 10) and another titled Happy Children, Happy Gandhi (Fig. 11). The latter work also recalls one of the earliest drawings by Maqbool Fida Husain (1915–2011) over the course of a prolific career in which he created numerous works on the Mahatma. In this early print, the artist enlists Gandhi for the cause of an elite furniture store in Bombay with the words, “Bapu loved to see happy and contented children: For your child’s happiness get a suite of fantasy nursery furniture” (Fig. 12).

Image courtesy the artist

Image courtesy the artist

Image courtesy the artist

The historic record shows that Gandhi broke his “self-purification fast” (undertaken against the sin of untouchability for 21 days) on 29 May 1933 with a glass of orange juice offered by his hostess, and a garland offered by a Harijan (or Dalit) boy. In the vision of an unknown artist painting the moment in a picture printed for the mass market, it is however the child who revitalizes the Mahatma after a grueling ordeal with an offer of fruit (Fig. 13). Similarly, a decade later when Gandhi undertook yet another 21-day fast in early 1943—to counter the colonial state’s impugnment of his non-violent motivations—his grandnephew Dhiren Gandhi imagines the child bringing solace to the fasting Mahatma in his woodcut titled Child—The Light Bringer (Fig. 14).

Image courtesy Priya Paul Collection@TasveerGhar, New Delhi

Image courtesy Anil Relia, Ahmedabad

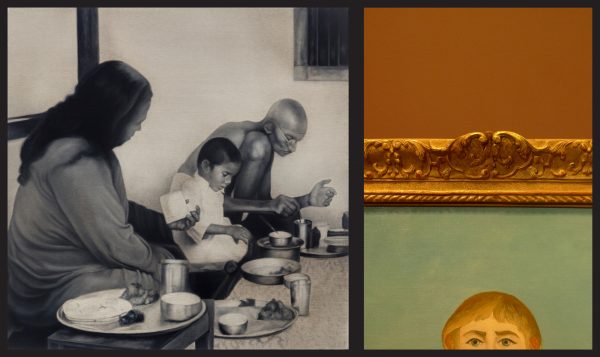

This sense of “deep proximity” has led Dodiya since the mid-1990s to produce a vast complex of moving and insightful works on the Mahatma across which the child flickers in and out, as in Morning Walk on Juhu Beach (Fig. 5), Bloodline (2004–06), and With a Child (2013). In a diptych titled Paramhansa Yoganand Reading a Note, August 1935, Dodiya cleverly retrieves from the archives a photograph documenting an important encounter in 1935 at Gandhi’s Sevagram Ashram near Wardha between the Mahatma and the US-based but India-born founder of the Self-Realization Fellowship, Mukunda Lal Ghosh aka Paramahansa Yogananda (Fig. 15). In his widely-read memoir, Yogananda writes in great detail about a meal with the Mahatma, but does not mention the child present on the occasion. Dodiya’s clever diptych pairing the photograph with Henri Rousseau’s Child with a Doll (1892) cues us to the child’s presence by Gandhi’s side, indeed occupying the space between the two men. The child in the photograph (and in Dodiya’s painting) is young Kanam Gandhi who, as his grandfather wrote in a letter from around this time to his grandmother, “always has his meals with me.” By his painterly act, Dodiya alerts us to the ubiquitous presence of children in and around the Mahatma on a daily basis.

One day Bapu told me, “Bakaa,

There are no exams in your sleep.

No one needs to pass anything so no one needs to fail.”

“Bapu, no studies, no keeping count.”

In our sleep, Bapu and I were taking a walk.

A crow took wing

From a nearby branch, cawing. I remembered.

“Bapu, I once saw a crow shitting on your bust.”

“So?”

“Just happened to remember.”

“Any busts in your sleep?”

“You’re here. Why would I need busts?”

“They don’t let a stone remain a stone,”

Bapu said, striding along.

“They don’t let a man remain a man,”

I agreed, keeping pace with him.

“They actually make busts, can you believe it?”

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi

65: 217; 78: 232.Narayan Desai, Bliss Was It to Be Young with Gandhi: Childhood Reminiscences. Edited by Mark Shepherd. Translated by Bhal Malji. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1988; and Sumathi Ramaswamy, Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience. New Delhi: Roli Books, 2020.