May 1. 2021

Frisson: The Aesthetics of Unexpected

Everyone knows at least one person who claims to hate opera. Ask that friend why and chances are they would say opera singers sound like screaming. It is true that opera is louder, or, more than other music genres, because the singer uses more resonance to fill the large hall with their voices. Meanwhile, some avid fans of operas might also love operas because of their screams. The magnificence of sound, as the opera performers deliver, gives us chills, which in particular is called frisson, the psychophysical response to auditory stimuli resulting in hair erection. According to Huron (2006), music-induced frisson functions similarly to what the Suspended Bridge Effect has shown: bodily reception can be misattributed to emotional causes. When the opera singer sings as loud as a screaming phantom, your heart beats faster and your breath becomes shorter, the frisson you are having is either instructing you “this is unworldly pleasure”, or “this is a fearful situation”.

Loud noises are not the only provoker of frisson; in fact, frisson can be experienced whenever a physically unexpected circumstance takes place. Huron theorized that six typical scenarios evoke the symptom of frisson: loud sounds, large volume, low pitch, infrasound, the scream, and the surprise. Loud sounds startle us because it signifies that we are very near to something, and this fact activates our defense reflex, making us more alert to the nearby environment. Large volume, although often mistakenly confused with loudness, means that the source of the sound has a large size (S.S Stevens). Similarly, our body forces us to be extra alert in such circumstances, because something extremely large has more power to hurt us. The fundamental difference between volume and loudness is the size of the sound sources. Fourteen violins in a symphony orchestra add up the volume of the violin section, while a microphone to one violinist makes it louder. The third sign for our nerves to get tight is low-pitch sounds because, in the animal kingdom, low-pitch sounds are naturally associated with aggression, which our human body remembers better than our minds. When we distinguish a low-pitch sound, we become more anxious. If the pitch gets low, then it falls into the realm of infrasound, in which the sounds have such low frequencies that humans cannot hear but only feel them via skin. Feeling the ambiance of infrasound gives us a haunted feeling, that something is going on in the air. The fifth one is the scream, which generates a huge amount of energy in the sound outlet. The reception translates such energy into the feeling of transcendence, which either makes the listening experience intimidating or elevating. Meredith Monk applied in Atlas the scream of monkeys, producing an akin effect to a human screaming but less cliched. The last provocateur is surprise, which underlines the abruptness of the ongoing flow of sounds. In these cases, human bodies would sense the changes in the environment and get prepared to act as the surroundings alter. These physical preparations drag us from the null comforts of daily life, and our sharpened sensations can either help us discover pleasure, or pain.

april 18,.2021

Looking at Sounds through Color-tinted Spectacles

A sound is a communicative tool that sets up a high bar before unveiling its true meanings – not that high actually, it just requires your patience – for sounds, unlike images, do not appear immediately, but rather unfolds as time passes. Even in cinematography where images and sounds are synchronized, our eyes and ears still perceive at different speeds, making the vision more spatially appreciated while the hearing more temporally appreciated. Understanding the reception mode helps us to better construct film design in a more harmonized way, one that is more coherent in its internal logic. However, the study on sounds is rather novel, thus scholars like Crook borrowed the existing paradigm or terminological concepts from the study of colors to look at sound designs. He briefed on this juxtaposition saying that “fine artists work with color. Sound artists work with a similar system of elements – sound. All sounds have a hue – a spectrum of nature. They can be defined scientifically, e.g., oscillation, reverberation, pitch, decibels in terms of level, or equalization” (76). I have no intention to decipher the physical existence of color and sounds but would instead introduce how to practically see sounds in parallel to colors in films.

The concept of three primary colors in fine art structures a way for us to understand where the visual inconsistency comes from. Blue, red, and yellow is believed to be original in the sense that they are sources of other colors and that they cannot be produced with whatever mixture of other colors. The haphazard juxtaposition of the primary colors will create a sense of chaos, like noises in a sound complex. Meanwhile, secondary colors can create a sense of harmony. Best Picture winner La La Land (2016) was a master on utilizing orange, purple, and green, in which way laid out the dreamy mixture of two different people: the pure Jazz lover and an aspiring actress. Their first encounter in a bar was filtered in orange tone, their romantic dance on Griffith Park was colored in purple, and their lovely piano duet City of Stars was taken in front of a green curtain. The soundscape in this film also benefits from the harmonized consensus on depicting a lively city with passionate people, so that the horns and birds co-existed with dramatic audition speeches as well as music floating from windowsills. The point of having this ambiance is to support the theme of the movie, to add charisma for Los Angeles so that it is reasonable why people come here to pursue their dreams.

This resembles what Matheson coined as “external reality” and “inner consciousness” for radio drama. The external reality is the imitation of specific items or events, which, according to my understanding, more like sound effects. The inner consciousness is about the “human essence”, a certain provocative icon that piques every listener’s visual imagination. Matheson concluded that the latter is more important than the former if a radio drama seeks success, just as Pear pointed out that “radio drama had failed in its attempt to establish visualization when a listener would say ‘I can see the man knocking the coconut shells together’”. Hence for sound design, it requires even a higher level than a visual design where the immediacy of the communication of meanings helps to reduce the potential inconsistency. That is to say, sound design should not boast its authenticity in sound production, although it is a valuable attribution, the central point is to make this assemblage of sound effects, music, speeches, etc. serving the need of storytelling. Meredith also mentioned that elements of music should be culturally consistent, in the sense that sounds do not confuse the audiences as professional noises.

april 18,.2021

The Sound of Movies

Movies are more than moving images, although we often unfairly use the verb “watch” to accompany our beloved cultural product, movies. Ever since the encounter of ideas between the great inventor Edison and the photography pioneer Eadweard Muybridge in 1988, the hope for having synchronized sounds accompanying moving images haunted film lovers. Early steps like inventions of Kinetoscope, Elgéphone, and Photophones led us to the final debut of sound film in 1919, approximately one century ago from now. It is an indispensable element of films, sometimes embedded so naturally that audiences forget the massive implementation of sounds in movies. To examine the use of sounds in movies with due respect, we should first have a shallow understanding of what, how, and why sounds are projected on images.

Three modes of listening characterize the reception of the sounds in movies. Causal listening, the most commonly adopted one, refers to the type of listening that with the help of visual clues, aims to identify the sources of the sound. Codal listening, on a deeper level, digs on the message generated by certain sounds, recognizing that each pronunciation yields a differential meaning. Reduced listening, unparallel to its name, requires most knowledge on the study of sound, for example, the timbre, texture, masses, and velocity of a sound.

According to Lacey (2009), there are four types of sounds, particularly in the case of movies. Dialogue sounds refer to the speeches in the movies, those languages that are transferrable into certain exact meanings as appear on subtitles. Sound effects are those non-verbal sounds that as well contain immediate yet recognizable information. Ambient sounds are atmosphere builders that are often displayed in lower volumes. Non-diegetic sounds are those sounds that, literally, can only be heard by the audience in the real world; the characters in the movie world cannot hear them.

Mixing usage of these audio materials in films is common practice because of the added value function of sounds. Coined by Chion (1990), added value describes the benefits of including synchronized sounds together with the images, literally, “the expressive and informative value with which a sound enriches a given image so as to create the definite impression, in the immediate or remembered experience one has of it, that this information or expression “naturally” comes from what is seen an is already contained in the image itself” (5). The power of sounds comes first from its verbal level, as a directing voice to frame our seeing to the images. Most apparently, the existence of subtitles lures us to read it, as a response to the speeches we hear from the movies. Furthermore, the sounds provide us with a certain scenario, or, a background mood that guides our vision in a natural way. This manipulation does not stop as a visual perception level but also reaches the emotional core. Two primary ways of enhancing emotions in relation to the images are adopting empathetic music and anempathetic music. Namely, when the music corresponds to the emotions provoked by the images, the audiences can better resonate thus be more empathetic towards the film universe, while on the contrary, when the music remains indifferent to the happenings inside the movies, sometimes the audiences’ emotions get reinforced in the contrast between the indifference and the shock.

April 10. 2021

The Myth of Understanding Art

The craze over understanding art is burning. Videos teaching people to understand art are becoming popular. Purchasing art courses is becoming a new trend among young parents. In a closer look at this connoisseurship fever, I wonder what exactly people are so eager to understand. Is it the meaning of an image? Then what is meaning, or, what does this word even mean?

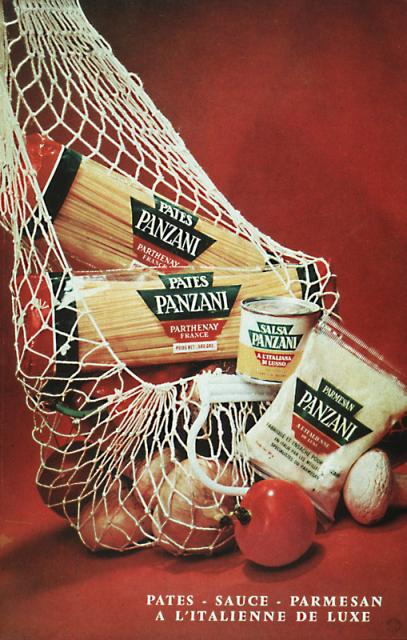

Roland Barthes, in his book Rhetoric of the Image (1964), first analyzed an advertising image as a prelude to his celebrated argument on the discussion of meaning. In this Panzani advertisement, Barthes saw meanings coming from three orientations: the linguistic message, the literal message, and the symbolic message. In this case, the linguistic message refers to the written text on the cover of the lasagnas. The language is the carrier of the message. The literal meaning refers to the elements shown in this image, literally, the half-open bag, tomatoes and peppers, the red and green, and the still placement of the items. The symbolic message refers to the suggested meanings of the elements in the image. For example, the half-open bag connotes the return from a market, the eagerness to get the delicious food outside of the bag, while the display of red and green tone, as well as the peppers and tomatoes, connotes Italianicity of the lasagnas.

However, an advertising image is not art, or at least in the most general sense. A piece of art usually does not expose its meanings in such a straightforward way. Take Van Gogh’s famous “ugly” oil painting The Night Café (1988) as an example. This painting effectively triggered millions of audiences the feeling of anxiety, almost like an inductive psychologist. We do not know what exactly is the thing that made us feel this way, and then we ponder. We take a second look at this painting, not because we are masochists who long for that anxious feeling, but because we are curious about the process in which we feel something in the absence of seeing something. Then we set out to learn about the painting techniques. We read about simultaneous contrast and optical mixing, and we watch videos introducing Van Gogh’s life story in a nutshell. Similarly, in the famous photograph Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance (1914), many people felt the pull of the picture. However, the picture per se does not seem to be outstanding in its composition, but the fact that this picture is taken just a few months before the first world war is crucial, because it makes us wonder what became of the three insipid farmers when the entire world was in turmoil. The date, together with the portrait, seems to contain a meaning that makes this picture worth investigating. The audiences will use their own life experience of knowledge to fill out the story when they look at the picture (and the date), and it is this process that sparks the audience’s interest in learning more about this photograph.

So, what is meaning? Sometimes we see something and we know something, just like in the advertisement image, but other times, when we see an artwork, we know something before we know what we see because we are not only seeing the artwork itself, but also our own imagination of the artwork. According to Qian, this is the aesthetics of concealment, due to which some artworks are so enthralling: the audiences are drawn to artwork because they participate in the process of meaning generation, in that very act of taking a second look.

In theory, semiotic scholars like Barthes believe that to understand what the meaning is of “meaning”, we have to first understand two concepts: the signifier and the signified. The signified is not a concrete thing, but a concept in our mind. A signifier, on the other hand, can be a text, image, color, sound, or anything that activates a sensory. The defining characters of a signifier are arbitrary (no natural connection to the signified), conventional (the signifier is conventionally attached to a signified in a specific region), and differential (each signifier is different from one another).

That said, meaning comes from the match of a signifier and a signified. In other words, when we successfully connect what we sensed (physically) and what we feel (in our mind), we understand the meaning. You might ask, it’s already hard enough to understand the artwork, why makes the definition of “understanding” so complex? This is not that esoteric, don’t frown. The act of us trying to understand the art is also a part of this paradigm. We are not really this interested in understanding the meanings of the artwork but instead trying to signal to the rest of the world that we are educated. To understand art is the signifier, to be perceived as educated is the signified. This is the meaning of us trying to understand the meanings of art. See, this is the myth of understanding art, and it’s not that far away from our life.

April 4. 2021

Rethinking Artworks

The debate topic “art that is not figurative is less art” nudges me to rethink how to understand artworks. The affirm side qualifies that art is the aesthetic reception of human beings, but there should be more orientations. For me, the definition of artwork stretches along two dimensions: the medium, and the message.

I understand the concept of medium from two perspectives: from the production end and from the reception end. From the production side, the medium is literally where the artwork embeds. It can be a canvas, a sculpture, or on Microsoft excel, just like Tatsuo Horiuchi. There is almost no limit to the range of mediums where an artwork can reside. Meanwhile, the context of the creation is also considered as the medium, because it is through that specific environment that we access to an artwork. An artwork is a selective mimic of the reality, and that selection criterion is based on the “precise historical context” of creation (Berger, 1972). The carrier of an artwork is more than technical tools or a skillful hand, but also the particular slice of time, the “social, political, and economical circumstances” that gave birth to the artwork (The Art Assignment, 2015). From the reception end, the genre of a medium is related to what channel of reception it activates. In other words, all media are mixed media with specific semiotic and sensory ratios (Mitchell, 2013). Signs and senses knock on our body, and certain mechanisms processes this stimulus, making responses to the artwork. For instance, looking at Mona Lisa close-up in the Louvre is different from seeing it on a computer pop-up: I will hold my breath and stare really hard at the authentic Mona Lisa, attempting to distinguish each brush even, but when it appears as a reproduced plain image, it becomes a cliché that I would not bother to look at.

The message of an artwork can also be understood in two layers: on an informative level, and on an experiential level. The information conveyed in an artwork can be powerful. Just like Azoulay (2013) has pointed out, artworks can be political in the way it secretly yet ubiquitously manipulates the audiences’ way of understanding certain events. For example, to photograph the deconstruction of a city in bright colors implies that the deconstruction is justifiable and should be commemorated instead of a shameful thing people should avoid mentioning. Art has the power of shaping people’s values, and thus influencing their life decisions. In this way, the information from an artwork can be manipulative, which is why artworks face strict censorship. On experiential level, artworks give the audience certain feelings that they cannot explain, and that experience is also part of the message. In the short film La Jetée, the director did not intentionally educate its audiences on an informative level, but with a genius display of still images and background music produces an apocalyptic atmosphere that shocks the audiences. What’s so exceptional about this film is neither the science fiction story per se, nor the experimental techniques, but the perfect combination of both that stirs an impressive feeling in the audiences across the globe.

March.28.2021

Reflection-

On Photography: In Plato’s Cave pp1-19

We, humans, yield the power of shaping memories to photographed images based on its capability of capturing objectivity. The human agency exists only at the moment, the “slice of time” (Sontag, 17) when the photographer frames the environment and clicks the shutter. After that, each revisiting of the photographs is rendering a porous body into a pseudo-reality. The invention of photography demonstrates an embalmment of the universe, rather than a mere mimetic of reality. The essence of photography as a technique lies in its objective nature, for “the image of the world is formed automatically, without the creative intervention of a man” (Bazin, 13). Therefore, “photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire” (Sontag, 4). Using photographs as proofs and testaments is prevalent because we trusted in them. This trust, however, can be violated in a way that when we put into so much power to photographed images, they can manipulate our memories of history. The camera is becoming an extension of human sensories, having us“converting experience into an image” (Sontag, 9). Just as our calendars take over the responsibility of remembering our family members’ birthdays, cameras take over the responsibility of memorizing a happening. As we become more used to, and more dependent on using cameras, our memories decline to function. Instead, we let the photo albums remind us of the past as if our past experiences are alienated from our bodies, something we lost, and then retrieved as we unfold those photos. The true danger lies in our self-deprivation of capturing our surroundings. In other words, inside the photobooks is a void of human agency, because we take these photos as our memories without reflection. Information becomes the truth so easily under such circumstances.

The power of the photographer, in this sense, is more intimidating, for their position of power is enduring. They not only manifest their power to the subjects by “seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have” (Sontag, 14) but also in carving one’s memories in the way photographs document the events. It is supposed to be those who are experiencing the happening to decide what to capsulate as precious memories, but with the presence of photographers, it is what they perceive as memorable that gets to last. They select what should be remembered by other people. The click on the shutter is a gunshot to a past that will disappear so thoroughly no nostalgia is directed towards it.