In Florida, iguanas are falling from the sky—and some chefs make them into tacos.

When cold snaps hit, their cold-blooded bodies will freeze and send iguanas tumbling from trees onto sidewalks and cars. Most of the year, warmer winters allowed these invasive reptiles to thrive and gnaw through gardens, destabilize seawalls, and clog up infrastructure. They’re absolute pests—but in parts of Central America, iguana meat is nicknamed “pollo de los árboles,” or “chicken of the trees.” What Florida residents see as nothing but a nuisance, others have long seen as dinner.

Putting Iguanas and other pests on the menu is a method of population control also known as invasivorism. While this practice is far from a new-age discovery, as temperatures climb and rainfall patterns shift, the rules of “survival of the fittest” are being rewritten as invasive species crash in.

For decades, the standard response to invasives is to kill them, bury them, and hope they don’t come back. Traditional solutions—like complex eradication campaigns, poisons with hazardous health & environmental implications, or costly physical removal—are rarely enough to solve the problem. They drain resources, buy only temporary relief, and are often doomed to fail against creatures that breed faster than budgets can keep up. Warmer waters, shifting rainfall, and longer summers around the globe create perfect breeding grounds for plants and animals to run unchecked through vulnerable ecosystems.

However, invasivorism offers a sharper tool: by turning pests into dinner, communities create a built-in incentive to keep removing them—because every meal taken from an invasive population is one less mouth eroding native ecosystems and biodiversity.

China’s Crayfish Economy

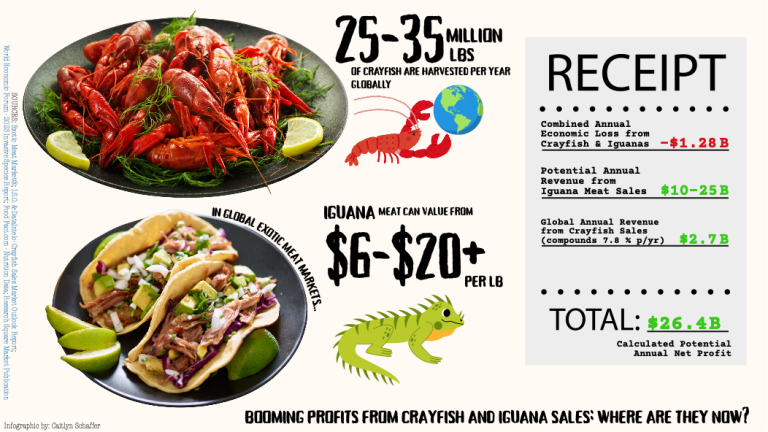

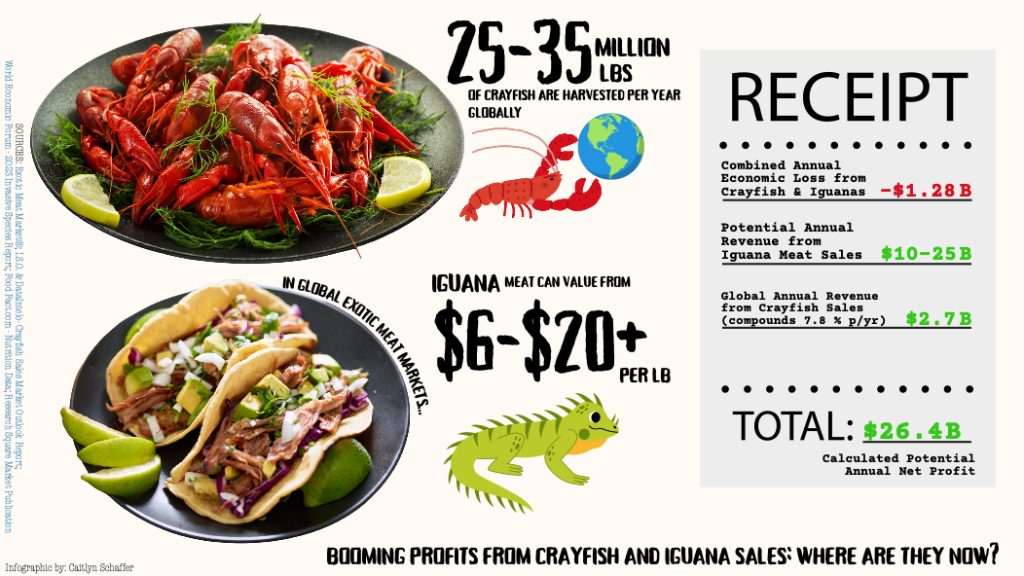

Every invasion leaves a price tag. Invasive species don’t just disrupt ecosystems but drain peoples’ wallets. Researchers estimate that invasive plants & animals worldwide cost communities more than $423 billion each year in damages/management. Thus as a solution, ecologists specializing in invasives have been advocating for invasives as an abundant food source.

Take the red swamp crayfish: while it’s a notoriously known invasive species around the world, this ravenously destructive critter also supports a ¥458 billion yuan (equivalent to ~$64.3 billion USD) aquaculture and catering industry in China. The crayfish is originally native to North America, specific to the region of Louisiana in the United States. When it was brought to Jiangsu Province in the 1920s, they ravaged rice paddies and aquatic crops, burrowed into levees and dams, and threatened local species by consuming nearly all of the available food. When locals began to capture and consume these pests in mass, it’s only scratched the surface of the numerous delicious delicacies that await!

Today, crayfish an extremely popular national dish—reported #1 on the top 10 most ordered food dishes on Chinese consumer app Meituan (Lawson, 2018). In Beijing, “Gui Jie,” or “Ghost Street,” is an entire road dedicated to crayfish and is filled with food vendors and statues for people to indulge in their crustacean cravings.

Whether it’s from the invasive mustard plant that smothers land and creates wildfire risk in the United States’ western region, to booming mosquito populations in high-latitude regions that pose increasingly threatening health risks for viruses like malaria and zika—China’s experience with crayfish on their environment isn’t an isolated experience. Across the nation, thousands of communities stricken with ecological crises caused by invasives now have the opportunity to turn their greatest pest into a delicious and profitable solution.

Tasting the Action

For local communities, the beauty of invasivorism lies in its accessibility. You don’t need federal policy to take part—you can start in your own kitchen!

Whether it’s going fishing for the fish overcrowding the local river, or pulling some overgrown plants from your backyard to put in your summer salad, this is an easy habit to integrate into daily life. Likewise, local restaurants as seen by Loco Cookers Flattop Grill in Florida, can explore new recipes and feature menu specials made from invasive plants and animals in town.

Of course, invasivorism isn’t a silver bullet: commercial harvesting should be monitored and practiced carefully, as not all invasives are safe for consumption. For local governments, regulatory support to streamline invasive population control harvesting is an important precaution. Therefore, constructing local incentive programs for citizens to participate in prevents the risk of greater environmental damage, unsafe procedures, and over-commercialization. Community programs like “Target Hunger Now” in Illinois are already training fishermen to harvest Asian Carp for food banks. In Florida, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean, iguana tacos and python chili are becoming more and more frequent as popular menu items. In Louisiana, crawfish boils are a famously popular to the region—a cultural dish that blends both authentic southern cooking and cajun cuisine.

Rethinking the traditional methods to pest control has posed many benefits—so perhaps the next ecological disaster can be served with a side of fries!

This blog was written as part of the PUBPOL111 course Communicating Climate Solutions: Writing for Impact taught by Professor Jennifer Turner.