The Rosetta Reitz Papers at Duke University comprise 41 linear feet and 30,750 items contained in 63 acid-free cardboard boxes and in more than 45 additional digital files. The materials, spanning the years 1929-2008, include research notes, photographs, audio and visual recordings, and published writings as well as handwritten and typed manuscript drafts, correspondence, business records, newspaper clippings, scripts for live performances, and over 200 books, many with detailed annotations by Rosetta Reitz, a feminist activist, entrepreneur, and founder of Rosetta Records. When our team began our research in Fall 2023, we had some ambitious goals in mind as possible outcomes – maybe a few public listening sessions, an advocacy campaign, a podcast, an exhibit, or even some public performances. We knew it wasn’t all possible, but we nevertheless dreamed big.

After starting to explore these materials, our definition of “big” changed, and our commitment to a slow, thoughtful pace deepened. The contents of this archive cut across twentieth-century US history and culture, including early blues and jazz live performances and recordings, paradigm-shifting technologies and legal systems, and waves of feminist and civil rights movements that challenged status quo structures of access to recording industry resources but never succeeded in leveling the playing field for women, and especially for Black women. How would we do justice to all the possible pathways that could open from research in this archive?

The album cover and liner notes for Sweet Petunias. Click an image to view and read. Source: Reitz, Rosetta. Sweet Petunias. Box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Our answer, perhaps counterintuitively, was to narrow our focus to a single compilation album, Sweet Petunias. Produced by Rosetta Reitz in 1986, this collection of songs performed by 16 singers and recorded between 1929 and 1956 does, as Reitz writes in her liner notes, represent “a cornucopia of choice songs and imaginative interpretations of women’s feelings.” For our research, those imaginative interpretations include not only those of the women who perform on the album, but also those of Rosetta Reitz herself.

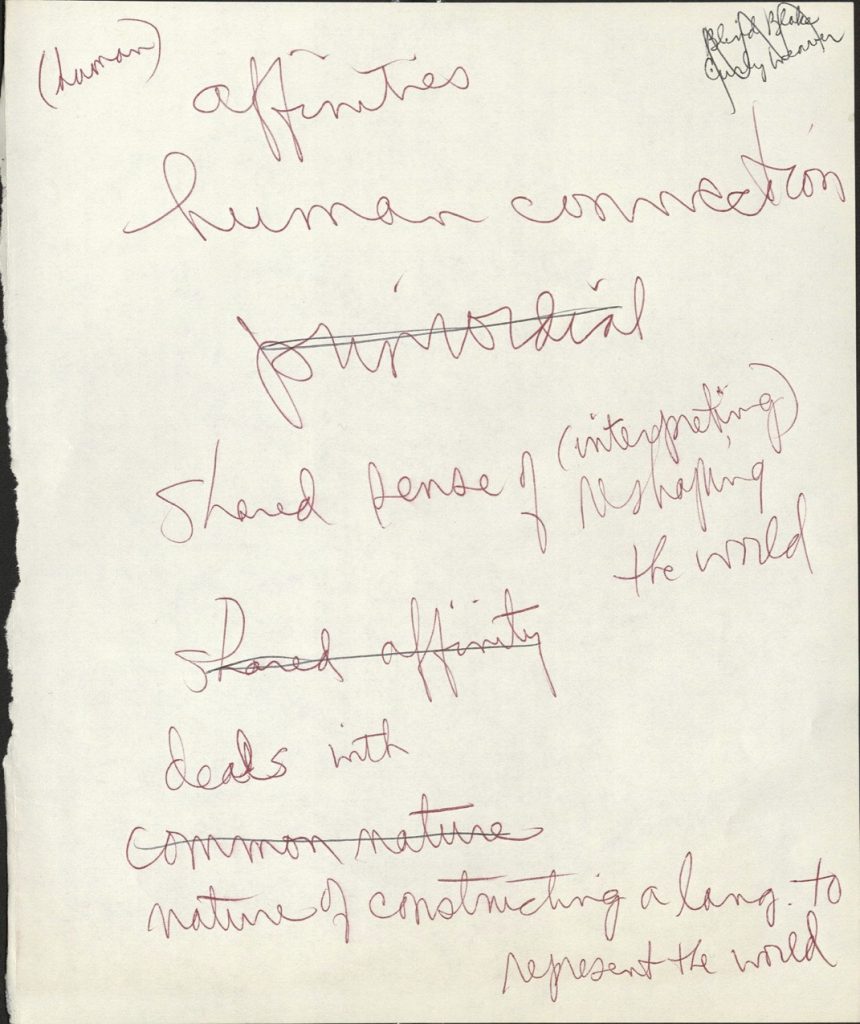

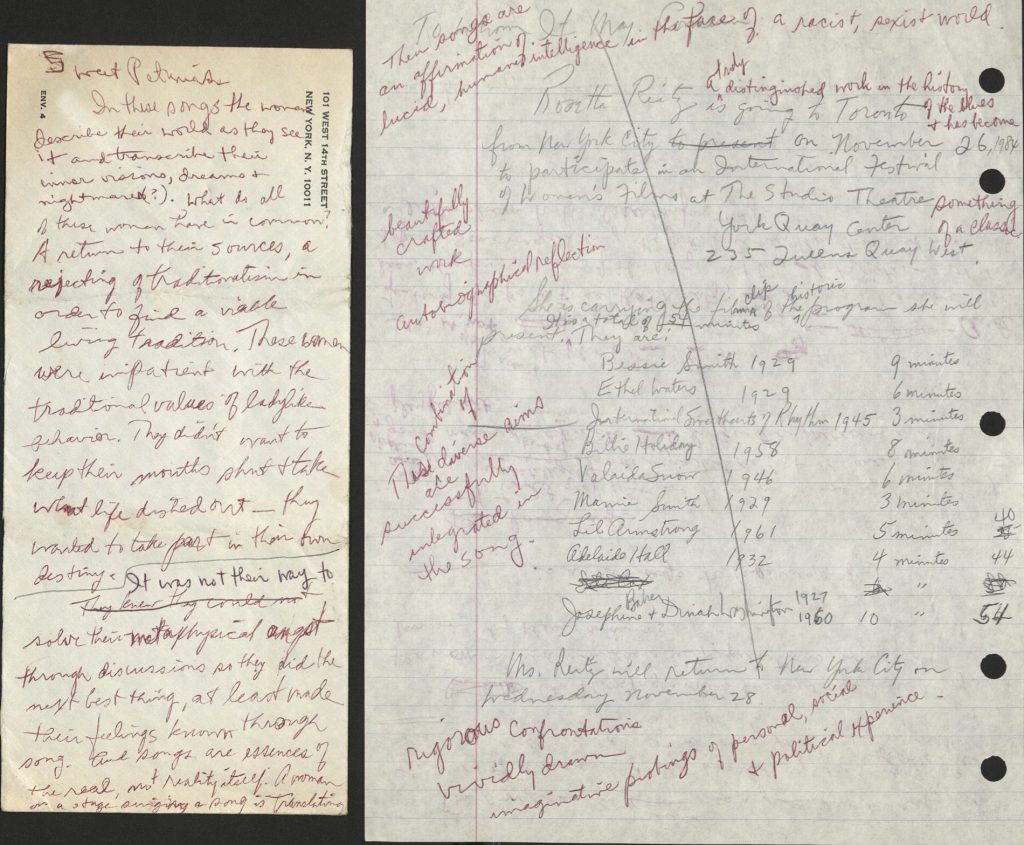

Images of Rosetta Reitz’s notes for drafting the Sweet Petunias liner notes. Source: Reitz, Rosetta. Box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. (Used with permission of Rebecca Reitz).

The “Sweet Petunias” folder in Box 4 of the archive exemplifies Reitz’s research and creative practices – sheets of notepaper covered in lists of descriptive words and phrases she might use in her writing, envelope backs filled with draft paragraphs replete with arrows, deletions, and annotations, newspaper clippings of the writings of music critics she admired, marked by her underlining of language she might repurpose for what scholar Daphne Brooks describes as “analytic appropriation.”

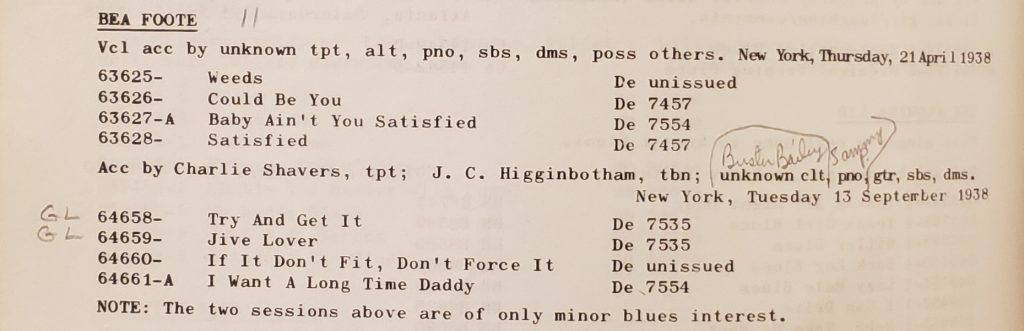

Bea Foote’s recordings as listed in John Godrich & Robert M. Dixon, Blues and Gospel Records: 1890-1943, pg. 230. Source: Reitz, Rosetta. Box 51, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Bea Foote in the New Pittsburgh Courier, January 9, 1932, pg. 6. Source: Newspapers.com.

The song selections and published liner notes on Sweet Petunias reveal the common themes that appear throughout all of Reitz’s work on jazz and the blues. Reitz maintained a commitment to highlighting Black women performers, many of whom had once been quite popular but whose recordings had become largely eclipsed by the legacies of their male counterparts. She meticulously searched for those women wherever they might be found. For example, we know from our exploration of the archive that when Reitz states that Bea Foote is “nowhere listed except for the fact that she had two recording sessions in 1938,” she could back up this statement through her careful combing of such volumes as Godrich and Dixon’s Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1942 (1969).

Images of Rosetta Reitz’s transcription of “Sweet Patootie” and “Sweet Patunia.” Reitz mistakenly names Lucille Bogan as “Louise Bogan” next to the “Sweet Patunia” title. Source: Reitz, Rosetta. Box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. (Used with permission of Rebecca Reitz).

Reitz was also attentive to the emotional impact of music and was determined to draw attention to examples of strength and defiance that could be found in blues lyrics and performance, as opposed to what she believed was an overemphasis on “victim variety” blues by other producers and writers. So strong was her opposition to this style of blues that she omitted from this album the song “Sweet Petunia,” (spelled “patunia” in some recorded versions) sung by the well-known Lucille Bogan. In the liner notes, Reitz explains this decision somewhat cryptically, but we see in the archival folder how she struggled with the song before deciding, “Sweet Patunia … is such a victim song that even with the right title – can’t use it.”

Her writing in these liner notes demonstrates both her strengths and her flaws, simultaneously celebrating the creativity and power of the women on the album, for example, while reducing the violent, racist world they had to navigate to “circumstances of history.” And what to make of the inclusion of Mae West, a White woman, and O’Neil Spencer, a Black man, on this album that otherwise seems intended to focus on the achievements of Black women? Reitz’s explanations are not completely persuasive, leaving us to develop our own conclusions.

The essays that follow emerge from the research of the undergraduate members of our team who undertook to explore some of the questions raised by this archive through the lens of one album, Sweet Petunias. Isabelle Zhang leads us on an exploration of the album cover design, examining both the floral imagery and the portrait of Aida Overton Walker. Trisha Santanam uses ideas from floriography to interpret Victoria Spivey’s song “Sweet Pease” and the interpersonal commitments that guided her throughout her life. And Lindsay Frankfort tackles the aforementioned question of Mae West’s presence on the album.

We’ve only begun our journey with the Rosetta Reitz archive. Along the way, we’re making corrections and additions to the collection guide, holding public conversations with researchers and performers (and researchers/performers!), seeking connections to archival collections and scholars elsewhere, and searching for the artists’ own perspectives where they might be overshadowed by Reitz’s powerful and relatively privileged presence. We offer these essays to you as an invitation to undertake your own exploration. There is plenty of work yet to do!