When I first looked at the Sweet Petunias album cover, Mae West’s name seemed to burst off of the page. It was exciting to see a familiar name, but I soon realized she was the only White singer featured on the album. Thus, my research primarily focused on why Rosetta Reitz, the producer and curator of Sweet Petunias, chose Mae West for this album and how West’s presence on the album relates to the agency of female singers. Through my research, I arrived at several different conclusions as to why West was included on this album, and within them a tension in her role in twentieth century performance.

West’s over-the-top and overtly sexual performances broke norms while relating to a wide audience, and she was well-known at the time of Sweet Petunia’s release, with a career spanning over fifty years; in fact, Reitz considered West to be the “biggest, baddest, sexiest beauty of all time.”[1] Yet her public persona drew from Black and queer performers who, unlike West, would never find wide audience acceptance in their lifetimes. Considering the spaces West carved out for female sexual expression alongside the advantages she experienced as a White performer helps us to understand tensions within Reitz’s project.

Mae West & Black Artists on Sweet Petunias

In order to understand Reitz’s singer selection process for Sweet Petunias, it is imperative to contextualize her activism. In 1980, Reitz started Rosetta Records, through which she curated and produced numerous albums that revived underappreciated female voices in jazz and the blues.[2] Sweet Petunias, released in 1986, showcases fourteen Black women, including Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, Victoria Spivey, Helen Humes, and Etta Jones, alongside West.[3] At the heart of her many projects, Reitz celebrated the popular second wave feminist ideal of sexual liberation, which refers to the freedom of individuals to pursue sexual desires uninhibited, regardless of one’s gender. Reitz effectively carried over her second-wave feminist spirit into the 1980s, which is when the bulk of her musical activism took place. Through Sweet Petunias, it seems that Reitz aimed to prioritize Black female voices above male and White voices and subsequently equalize Black womanhood and sexuality with that of their White colleague on the album.

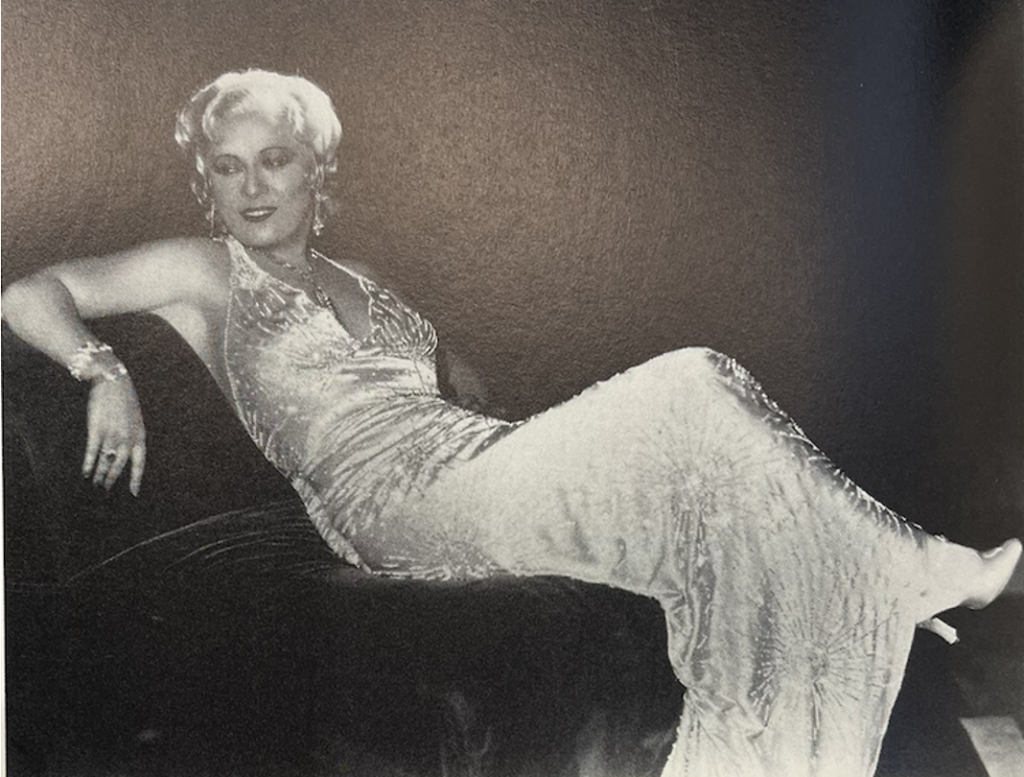

Above all, Sweet Petunias is an album that celebrates the liberation of female sexuality from the expectations of patriarchal society. The songs on Sweet Petunias self-consciously shy away from so-called “victim variety” blues, a style of blues where women sing about mindlessly pining over men.[4] Instead, the songs emphasize the dominance and confidence of a sexually liberated woman.[5] For example, West sings “My Man Friday,” a song about using a different man each day of the week for sexual and material gain.[6] The song is full of sexual innuendos, like having a “potluck” of men on Saturday when she cannot decide which man she wants to see, and other more overt sexual references, like “he satisfies me” and is “guaranteed to thrill me.”[7] Beyond their lyrics about enjoying sex rather than being its victim, the women on the album also portrayed these sexually liberated personas through their stage presences, audience interactions, style, and costumes. Notably, West’s on-stage persona included a “flamboyant style,” “extravagant costumes,” “boldness,” and a “larger-than-life character” who is “humorous and charming” when she sang and engaged with the audience.[8],[9] West’s lyrics and performances were a departure in popular culture during the 1940s and ’50s, when discussing sex was taboo.[10]

Mae West’s Career & LEgacy

West was the best known of the performers included on Sweet Petunias at the time of its release. In her career, which spanned the 1910s to the 1970s, West consistently broke norms of femininity and sexuality in each industry in which she worked. She began in vaudeville and cabaret, where she developed a successful stage persona equal parts funny and sexy, but her “particular style of sexual performance” left audiences uncomfortable and failed to appeal to local crowds.[11] Her stage presence and persona were much more palatable for larger theatrical venues which attracted more diverse crowds.[12] Knowing this, West switched to the bigger Broadway stage, where she wrote and starred in several controversial plays.

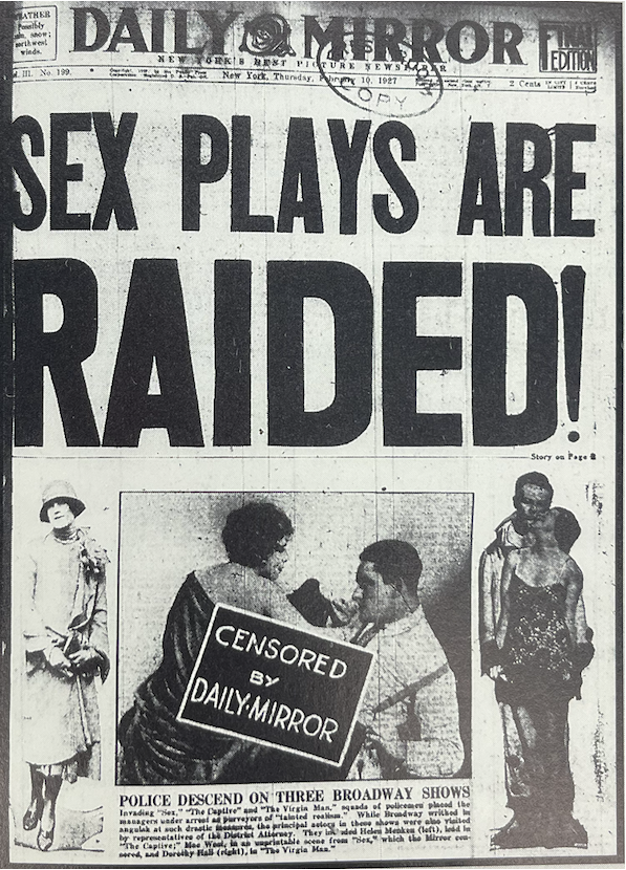

Some of her theatrical hits include Sex (1926), a show involving explicit sexual actions and risqué dialogue, and The Constant Sinner (1931), a show which featured an all-Black ensemble and explored the taboo subject of interracial love.[13],[14] While these shows caused a stir in the media and faced censorship, West’s star rose, and she soon signed a contract with Paramount Pictures in 1932.[15],[16],[17]

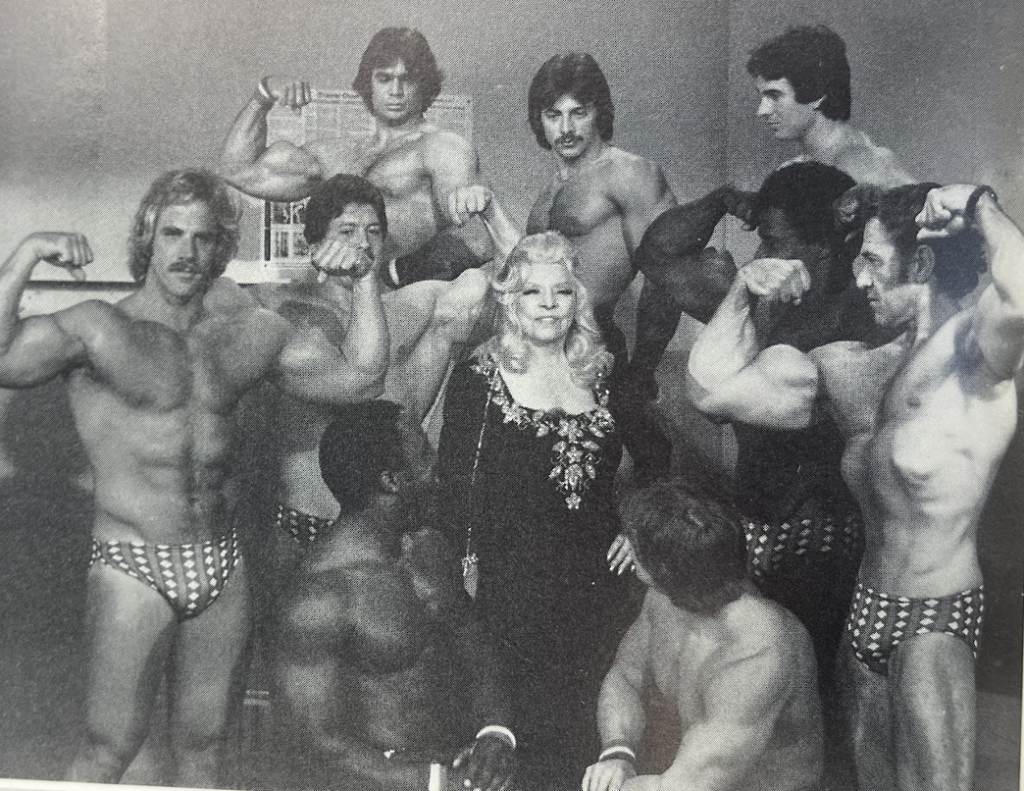

West starred in numerous feature films, released successful songs and albums, and became a household name for decades to come.[18] Even at 87 years old, during her last project, the movie Sextette, West portrayed a sexual and outspoken female protagonist, demonstrating that she consistently engaged with taboo themes and unapologetically embraced her redefined female sexuality.[19] (In one scene in Sextette, she tells a locker room full of men in speedos, “Is that a pistol in your pocket or are you just pleased to see me?”[20])

West’s humorous and sexually overt persona drew upon performance genres innovated by her peers. Her dirty blues singing style, a style that involves crude language and references to sex, was inspired by Black performers like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith.[21] Additionally, she largely learned stage-presence and audience-engagement techniques from cross-dressers like Bert Savoy, vaudeville icons like Eva Tanguay, and singer-comedians like Sophie Tucker.[22],[23]

West’s complicated act didn’t fit within the palatable box of femininity she was prescribed. In fact, in 1944, Parker Tyler referred to Mae West as a “female impersonator,” a term that has been positively reclaimed to describe West’s queer-coded, Black-coded, and sexually overt persona.[24] Her act was initially critiqued as “grotesque, a man in drag, a joke on women, and not a woman” at all.[25] However, the very existence of critiques like this demonstrates the truly norm-defying and inclusive nature of her performance and persona.

Few people, White or Black, including many of West’s colleagues on this album, enjoyed the success she experienced. West portrayed a sexually liberated female, effectively breaking boundaries and creating opportunities for a slew of other outspoken, empowered, and norm-breaking female performers. Thus, while Reitz states in the Sweet Petunias cassette notes and liner notes that Mae West was included on the album because she “listened to the race records. She loved them. She tried to imitate them,” West’s unmatched legacy and redefinition of female sexuality contributed to this decision.[26]

Whiteness & Mae West’s Debt to Black Women

However, while West’s legacy deserves to be recognized on this album, she would not have achieved this level of success without the societal advantages she enjoyed due to her Whiteness and traditional beauty. In other words, unlike her Black colleagues on the album, West held power on and off the stage. Therefore, West’s inclusion on this album, along with the fourteen other Black women, glosses over the complicated social and racial reasoning behind her legacy. In fact, West’s inclusion, if misunderstood, may perpetuate Black blues erasure, and wrongly equate female struggles across racial lines. While the familiarity of West’s name on the album may assist in uplifting the other Black female voices, her presence could also overshadow the Black women among whom she is included. (Furthermore, it is important to note that while Reitz was an activist, she was also a businesswoman who wanted to sell albums: West’s popularity might have helped boost interest in the compilation.)

Overall, Sweet Petunias successfully represented the second-wave feminist idea of sexual liberation, but it did not address the larger issue of female agency in the music industry in all its complexity. This agency is a privilege that performers acquire in asymmetrical ways, dependent upon race, sexuality, and class, as well as gender. Mae West enjoyed not only a level of fame but also of agency within her career that others on Sweet Petunias structurally could not. Throughout the twentieth century, Black women in the music industry were excluded from achieving outcomes similar to that of West, and such exclusions remained in place in the 1980s, when Reitz collected these songs. While some of the Black singers on the album achieved successful careers in their own right, they were not widely known as the “biggest, baddest, sexiest” beauties “of all time.”[27] When we celebrate the sexually liberated personas of woman performers, these asymmetries should be kept in mind.

Lindsay Frankfort is a junior (Trinity ’26) studying History and Gender, Sexuality, & Feminist Studies.

continue reading

End Notes

[1] Rosetta Reitz, Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West liner notes, box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008, Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

[2] “Background,” Rosetta Reitz’s Musical Archive of Care, Duke University Bass Connections, accessed May 2, 2024, https://bassconnections.duke.edu/project-teams/rosetta-reitzs-musical-archive-care-2023-2024.

[3] “Sweet Petunias: Independent Women’s Blues, Volume 4,” Discogs, accessed May 2, 2024, https://www.discogs.com/release/3118599-Various-Sweet-Petunias-Independent-Womens-Blues-Volume-4.

[4] Reitz, Sweet Petunias liner notes.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Reitz, Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West liner notes.

[9] Reitz, Sweet Petunias liner notes.

[10] “Sweet Petunias: Independent Women’s Blues.”

[11] Marybeth Hamilton, When I’m Bad, I’m Better: Mae West, Sex, and American Entertainment (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987), 21.

[12] Hamilton, When I’m Bad, I’m Better, 21.

[13] Pamela Robertson, Guilty Pleasures: Feminist Camp from Mae West to Madonna (Duke University Press Books, 1996), 30.

[14] Robertson, Guilty Pleasures, 34.

[15] Frederick W. McQuigg, “Fire Bells Clang as ‘Sex’ Arrives,” August 25, 1930, box 38, folder Mae West, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008, Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

[16] Hamilton, When I’m Bad, I’m Better.

[17] Ramona Curry, “Mae West as Censored Commodity: The Case of Klondike Annie,” Cinema Journal 31, no. 1 (Autumn 1991): 59, https://doi.org/10.2307/1225162.

[18] Reitz, Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West.

[19] David Polk, “Mae West Made This ‘Insane’ Film in Her 80s,” PBS, March 1, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/insane-film/14748/.

[20] Polk, “Mae West Made This ‘Insane’ Film.”

[21] Robertson, Guilty Pleasures, 35.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Reitz, Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West.

[24] Robertson, Guilty Pleasures, 29.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Rosetta Reitz. Sweet Petunias cassette notes, box 4, folder Sweet Petunias, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008, Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

[27] Reitz, Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West.

Bibliography

Bergeron, Ryon. “The Seventies: Feminism Makes Waves.” CNN. August 17, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/07/22/living/the-seventies-feminism-womens-lib/index.html.

Borders, William. “Mrs. Thatcher Divides Feminists: A Woman in Power, but Not ‘a Sister.’” The New York Times. August 27, 1979. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/08/27/archives/mrs-thatcher-divides-feminists-a-woman-in-power-but-not-a-sister.html.

Brown, Jayna. Babylon Girls: Black Women Performing and the Shaping of the Modern. Duke University Press Books, 2008.

Carby, Hazel V. “White woman listen! Black feminism and the boundaries of sisterhood.” In Black British Feminism, edited by Heidi Safia Mirza, 45-53. Routledge: London and New York, 1997.

Dillard, Angela. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Now?: Multicultural Conservatism in America. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

Goldstein, Norman. “Come Up and See Mae West Sometime.” Quad-City Times, August 2, 1970. https://newcomwc.newspapers.com/image/303974804/?terms=Mae%20West&pqsid=6bELBwP5ikzepH2OBbwLg%3A48647%3A1612554370&match=1.

Hamilton, Marybeth. When I’m Bad, I’m Better: Mae West, Sex, and American Entertainment. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987.

McQuigg, Frederick W. “Fire Bells Clang as ‘Sex’ Arrives.” August 25, 1930. Box 38, folder Mae West, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Polk, David. “Mae West Made This ‘Insane’ Film in Her 80s.” PBS, March 1, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/insane-film/14748/.

Power, Marilyn. “Falling Through the ‘Safety Net’: Women, Economic Crisis, and Reaganomics.” Feminist Studies, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 31-58, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3177893.

Reitz, Rosetta. Sixteen Sultry Songs Sung by Mae West liner notes. Box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Reitz, Rosetta. Sweet Petunias Cassette Notes. Box 4, folder Sweet Petunias, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Reitz, Rosetta. Sweet Petunias liner notes. Box 4, Rosetta Reitz papers, 1929-2008. Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Robertson, Pamela. Guilty Pleasures: Feminist Camp from Mae West to Madonna. Duke University Press Books, 1996.

“Rosetta Reitz’s Musical Archive of Care.” Duke University Bass Connections. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://bassconnections.duke.edu/project-teams/rosetta-reitzs-musical-archive-care-2023-2024.

“Sweet Petunias: Independent Women’s Blues, Volume 4.” Discogs. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.discogs.com/release/3118599-Various-Sweet-Petunias-Independent-Women-Blues-Volume-4.

Photos reproduced from:

Hamilton, Marybeth. When I’m Bad, I’m Better: Mae West, Sex, and American Entertainment. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987.