The Unlikely Memorial at Bennett Place 1865-2024

The great Civil War surrender at Durham’s Bennett Place farmhouse in 1865 happened at this place by coincidence and became national and international news. The surrender negotiations took place at Bennett Place because the Generals and their attendants met along the road between the opposing forces and the Generals adjourned to the house to confer in private.

The story of how the Bennett Place Memorial was eventually created was also marked by coincidence.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News 1865

The generals meet at Bennett Place, Harper’s Weekly, 1865

1865- The Armies meet and the Conflict ends

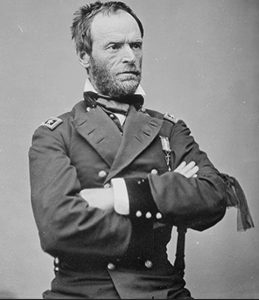

In early spring of 1865, following his eight-month campaign of total war and destruction from Atlanta to Savannah and through South Carolina, William Tecumseh Sherman brought the only remaining organized Confederate army to ground in Piedmont North Carolina. The final decisive battles between the 16th and 21st of March 1865 at Bentonville and Aversboro in south central North Carolina sealed the fate of the Confederate Armies.

Library of Congress

Sherman’s Federal forces were overwhelming. They were ever more plentifully supplied and reinforced from secure ports and rail heads in Wilmington and Goldsboro in eastern North Carolina. Johnston’s remaining Confederates retreated and spread west more than fifty miles from Hillsborough along a long arc to Greensboro and beyond. On April 9th, 1865 word slowly spread that Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had surrendered as they retreated west from Richmond. The Confederates in North Carolina, though better supplied than Lee’s vanquished troops, were much less well-equipped than the Federals. Though ammunition and ordnance were in short supply, the Confederate army remained a viable force to carry on the fight. The Confederate Governor, local leaders, and General Johnston recognized the hopelessness of the situation even as the fleeing Confederate government did not.

Unable to check the Union advance, by the 10th of April 1865, the armies came face to face just beyond the North Carolina capital in Raleigh. Generals Sherman and Johnston exchanged notes and agreed to a cease-fire and to meet between the lines along the Hillsboro road parallelling the path of the NC Railway. On the appointed day the Generals and their escorts met on the road just west of Bennett Place and rode together to the cabin to negotiate and decide whether destruction would continue or cease in central North Carolina. Their task required three meetings because the reaction to the assassination of Lincoln changed the national atmosphere between their first and second conferences. The mutual resentment of the two armies after years of struggle remained, and was counterbalanced by war weariness and the fear, widely expressed, that devastation would follow the combatants if resistance continued. The ceasefire was honored warily on both sides. Confederates were widely viewed as traitors by the victors, and the victors were viewed as vandals by the defeated.

The peace, finally enacted at Bennett Place near Durham Station on April 26th, meant that the great rebuilding of reconstruction and the eventual readmission of the rebellious States might fulfill the promise of reunion, emancipation, and the end of slavery in the United States.

1923: Should the site of the surrender become a Monument?

From its initial proposal, identifying Durham’s Bennett Place surrender site as a Civil War memorial was controversial. The Samuel Tate Morgan family who ultimately donated the site and the funds for the Unity Monument had only recently inherited the farm from their father. Morgan was

a mu

Bennett House encased in Brodie Duke’s protective shed. ca 1920

Samuel Tate Morgan, Ca 1900. Rubenstein Library, Duke University

Samuel Tate Morgan had acquired the Bennett Place property after the death of Brodie Duke, eldest son of the Duke tobacco family, in 1919. Brodie Duke’s original intention in purchasing the Bennett property had been to sell the surrender house for reassembly and display at the World Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Duke could find no buyers for the house, and it sat vacant for nearly 20 years. Samuel Tate Morgan’s vision was to create a memorial to the surrender at Bennett Place and to donate the site and memorial to the State of North Carolina.

Bennett House ca 1875, Bennett Place Historic Site Collection

“Lost Cause: supporters in North Carolina seemed to be against Morgan’s proposal from the beginning. First, they argued, it was inappropriate to memorialize the surrender. Secondly, the cottage where the Generals met was hardly worthy of preservation.

Just as initial plans to create the memorial were announced in the early Spring of 1921, a disastrous fire destroyed the original Bennett farmhouse where Johnston and Sherman met. Purportedly set by vagabonds, no responsibility for the fire was ever established. Only the chimney remained to mark the spot of the surrender.

Also by the Spring of 1922, the Legislature of the State of North Carolina appointed Reuben O Everett, himself a member of the Legislature, as a commissioner. Everett took leadership in coordinating fellow commissioners and in working with the Morgan family as plans for the memorial and dedication moved forward.

Atlanta Constitution 11/24/23

The Unity Monument as conceived by the Morgan Family and the Commissioners was different from the typical Civil War memorials of the day which depicted a Confederate or a Union soldier . The twin columns of the Unity Monument represented the North and the South and were joined by a frieze inscribed, “Unity.” The message was very different from that in most contemporary memorials.

Moving forward with the creation of a monument to national unity, commissioners planned a suitable dedication ceremony including, it was hoped, a speaker of national importance.

President Calvin Coolidge was the first choice and met with Everett and other commissioners in two appointments at the White House to discuss the possibility. Ultimately, Coolidge declined to participate because of the press of business at the end of the Congressional term.

Next, Secretary of War John W. Weeks was invited and initially accepted. Local dissension, primarily in editorials and letters to the editor in the newspapers throughout North Carolina, persuaded Meeks to withdraw from participation in late October just before the ceremony.

Southern Historical Collection, University of NC Chapel Hill

Various distinguished historians were considered, but time was short and ultimately Julian S Carr, industrialist and philanthropist, originally from Chapel Hill NC, a Memorial Commissioner and the honorary life commander, and thus, “General,” of the United Confederate Veterans, seized the opportunity and delivered the primary address.

Julian S Carr, Southern Historical Collection, UNC Chapel Hill

Carr is now remembered chiefly for claiming in his dedicatory speech at UNC’s Confederate Monument (Silent Sam) in 1913 that he whipped a woman of color in the early Reconstruction period for insolence. Ten years later, in November 1923, Carr delivered his dedicatory address at Bennett Place.

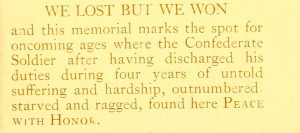

Entitling his speech “Peace with Honor,” Carr praised the Confederate veterans and their cause as he acknowledged the moment which reunited the nation. Surrender was a word that Carr used in his speech, but it was surrender with terms and conditions. Carr’s subtext, as stated explicitly in his self-published printed version was, “we lost, but we won.”

In Carr’s speech, the war was not about slavery, rather it was about states’ rights, and the defeat was the result of the failure of the requisite economic and military resources. Providence, he noted, which is unknowable, had made the final determination to which the noble Southerners must bow. Carr, nonetheless, celebrated the subversion of Reconstruction and the reestablishment of white supremacy through Jim Crow.

Carr participated as both a Bennett Place commissioner and as the speaker despite the objections and boycott of the ceremonies by the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Julian S Carr chapter. The boycott was based on objections to the memorialization of a site honoring an “ignoble surrender.” Despite this, as the most powerful former Confederate in Durham, as an industrialist and philanthropist, and as an undeterred supporter of the “Lost Cause” ideology, “General” Julian Carr in his Confederate veteran’s uniform, addressed the assembly.

General Carr, center, in Confederate veteran uniform. From Wyatt Dixon Collection, Rubenstein Library, Duke University,

Dedication audience and Unity Monument, From North Carolina Collection, Durham Public Library

Reuben Oscar Everett, Champion of the Bennett Place Memorial

RO Everett, City Attorney, 1909.

A distinguished civic leader in Durham and descendant of colonial-era settlers in northeastern North Carolina, R.O. Everett was the long-time chairman of the Bennett Place Memorial Commission in 1965. R.O. Everett was elderly at the time of the centennial celebration, but he was practicing law with his wife and son. Everett was the senior member of the North Carolina Bar Association. After his education at UNC Chapel Hill and Law School at Trinity College in Durham, Everett began his public career as the first Durham City Attorney in 1909. Most honored as a lawyer for lectures on taxation and the primacy of the rule of law, Everett lived his principles as a prosecutor. In a widely-reported prohibition-era case in the 1920s, Everett prosecuted and convicted a bootlegger who subsequently threatened his life with a pistol. Everett took this risk despite recording his occasional consumption of alcohol in his pre-prohibition diary.

R.O. Everett at Bennett Place, 1965. Rubenstein Library, Duke Univ.

By 1965, Everett was well-known as a business leader, a legal scholar, an antiquarian, a former NC Legislator, and as the long-time champion of the preservation of Bennett Place as a monument to national unity.

Everett wrote to then Durham Mayor Wense Grabarek:

The theme of our program,as I understand, will be National Unity, the Spirit of which was reborn in the agreement, April 18, 1865, arrived at through the friendly negotiations of General Sherman and General Johnston, but which had been authorized by President Lincoln immediately before his death and approved by President Davis. The conduct of General Sherman in the negotiations had a touching appeal to the American people and did much to revive the spirit of national unity.

1965, Southern Historical Collection, UNC- Chapel Hill- Everett Papers.

The rededication and Centennial of the surrender in 1965 came fully 42 years after Everett, in 1922-23, had carefully guided the donation of the Bennett Place site and the creation and dedication of the Unity Monument there.

1965- 100 Years after Surrender- a Centennial Ceremony

Vice President Humphrey Rededicates the Bennett Place Monument, April 1965-

This incongruous 1965 newswire photo portrays three distinguished Americans, left to right: Hubert H. Humphrey, Vice President of the United States, Reuben Oscar Everett, former Legislator and a Bennett Place Commissioner beginning in 1922, and Daniel (Dan) K. Moore, NC Governor and later NC Supreme Court Justice.

These dignitaries gathered for this photo in the doorway of the Bennett Place farmhouse kitchen in Durham NC at the centennial ceremony of the Civil War surrender negotiations at Bennett Place. The purpose of the Centennial Event was to rededicate the site to national unity in a time of notable disunity.

To modern eyes, Humphrey and Moore look quaint in their Jetson suits with the narrow lapels and the narrow ties of the early 1960’s. The presiding dignitary, Reuben O Everett, age 87, looks positively Edwardian with his wing collar, boutonniere, frockcoat, and homburg. RO Everett had been a commissioner at Bennett Place since before the original dedication of the Memorial in October of 1923.

The Centennial Celebration that Humphrey addressed in April 1965 occurred at a moment of historic change and at a turning point in the history of the United States: within the previous 18 months, President Kennedy had been assassinated; President Johnson and Vice President Humphrey had been elected; and the portfolio of laws comprising the Great Society was enacted. Between 1964 and 1965, the CIvil Rights Act; the Voting Rights Act; the Fair Housing Act; Medicare; Medicaid; Immigration Reform; Aid to Education; Headstart; NPR; the Public Broadcasting System; and many other Federal programs were put in place to encourage social and economic justice. But that fight was far from over. The Vietnam Conflict was widening and darkening the nation’s horizon, eventually upending Lyndon Johnson’s chance for a second term and further social progress.

Durham Morning Herald, April 1965

Humphrey, a native of Minnesota, was complementary of North Carolina and the Durham area, especially the universities and the recently opened Research Triangle Park. But Humphrey did not whitewash his own social views: the prevailing racism of the previous hundred years, he said, as it had existed in the South and elsewhere in the United States, was an insidious curse and was ongoing.

Vice President Humphrey’s presence in Durham was major local news. Duke University served as host to Humphrey’s entourage and had him speak at a Law School event. The Ku Klux Klan, as a counter-protest, held a large white supremacist rally nearby. Despite fears of interference at the Bennett Place event, there was no disruption.

In his remarks at Bennett Place, Humphrey explored the scourge of racism, and he extolled the improvements promised by the Great Society. He spoke before an audience that included a few men in Confederate garb and a few known members of the Ku Klux Klan. He called for a greater and more inclusive America.

A transcript of Humphrey’s speech was preserved:

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00442/pdfa/00442-01568.pdf

Bennett Place Centennial Program and photograph, 1965

1984

After the 1965 Rededication the site continued to be used for Boy Scout Jamborees and the occasional reenactment event but by the late 1970s, momentum built for a visitor’s center/ museum and fired by the enthusiasm of William Vanavuk, a scientist brought to NC by the Research Triangle park and other locals The Visitor Center building was dedicated in 1984, and included accessible restrooms, a gift shop, staff office space and a museum and auditorium.

2024 and beyond- Bennett Place Today

Photos by Sallie Scharding, Scharding Designs, Chapel Hill NC

Today the Bennett Place Historic Site is a popular and well-established State institution with a professional staff, a Visitor’s Center, interpretive displays, regular programming, and strong local support. Occasional reenactments, including Christmas, remain popular activities at the site along with the firing of Civil War era weapons, but the house, kitchen and outbuildings, and the site’s Unity Monument remain the heart of the memorial.

The proximity of highways, local events of interest, ample facilities, and parking, encourage tourists:. school group visits comprise a substantial proportion of visitors. This increasingly diverse population presents opportunities to demonstrate the relevance of history.

The original Bennett Place house and kitchen burnt under suspicious circumstances in the spring of 1922 and were rebuilt using period materials in the early 1960s. Civil War-era owner James Bennett’s personal papers and, most importantly, his farm ledgers from the 1840s, are preserved. The records and the houses of less wealthy, non-slaveholding farmers from the Piedmont North Carolina of this era are rare.

Emphasizing the context of the history of life on the small farms in central North Carolina, and programming highlighting the role of the location as far back as the history of indigenous peoples, are good places to begin to address the relevance of the Bennett Place Memorial in its second century.

Further Reading:

Bennett Place Memorial Commission., and North Carolina. State Department of Archives and History. Dedication Exercises, Bennett Place Restoration, Durham, North Carolina : Sunday, April 29, 1962, 2:30 P.M., the Durham Music Center. Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Archives and History, 1962.

Bennett Place State Historic Site (Agency : N.C.). Bennett Place Quarterly. Durham, N.C.: The Site, 1999.

Bennitt, James. “Papers, 1820-1962 ; (Bulk 1830-1850).” 159 items. Duke University. Rubenstein Library, 1962.

Bradley, Mark L. This Astounding Close : The Road to Bennett Place. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=413237.

De Capite, Michael. The Bennett Place. Falcon Press: London, 1948.

Dollar, Ernest A., Jr. Hearts Torn Asunder : Trauma in the Civil War’s Final Campaign in North Carolina. El Dorado Hills : Savas Beatie, LLC, 2020., 2020.

Dunkerly, Robert M., and Savas Beatie. To the Bitter End : Appomattox, Bennett Place, and the Surrenders of the Confederacy. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie LLC, 2015.

Ervin, Samuel James, and United States Congress Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Bennett Place Commemoration. March 11, 1965. — Ordered to Be Printed. Washington, DC: Verlag nicht ermittelbar, 1965. http://www.nationallizenzen.de/angebote/nlproduct.2009-02-20.2266515664 Inhaltsbeschreibung der Sammlung und Zugangshinweise

http://docs.newsbank.com/select/serialset/126497FF2AD4FB28.html.

Everett, R. O. “R.O. (Reuben Oscar) Everett Papers, 1913-1971.” Produced: 1913-1971., Duke University, Rubenstein Library, 1913.

———. “Kathrine R. Everett and R. O. Everett Papers, 1851-1993.” In Kathrine R. Everett and R. O. Everett Papers, 1851-1993, edited by University of North Carolina Chapel Hill: Southern Historical Collection, 1993.

Hoar, Jay S. “General” James Reid Jones, January 4, 1845-June 29, 1945 : Last Witness to Bennett Place Surrender. Columbus, Ohio: Blue & Gray Enterprises, 1985.

Menius, Arthur C., III. “James Bennitt: Portrait of an Antebellum Yeoman.” North Carolina Historical Review 58, no. 4 (1981): 305-26.

Merchants, Association. Durham Illustrated : Containing a Comprehensive Review of the Natural Advantages and Resources of Durham. [in English] Durham, N.C.: Durham, N.C. : Published under authority, The Merchants Association, printed by Seeman Printery, 1910., 1910.

North Carolina. State Department of Archives and History. Bennett Place : State Historic Site. Raleigh: N.C. Dept. of Archives and History, 1962.

Sacchi, Richard R., Terry H. Erlandson, and Unit North Carolina. Historic Sites Section. Research. An Intensive Archaeological Survey of the Bennett Place, Durham County, North Carolina.: 1980.

Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag : How Surrender Defined the American Civil War.Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press,, 2019.

United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Bennett Place Commemoration. Washington: GPO, 1965. http://www.lexisnexis.com/congcomp/getdoc?SERIAL-SET-ID=12662-1+S.rp.122 View full text.

Vatavuk, William M. Dawn of Peace : The Bennett Place State Historic Site. Durham, NC: Bennett Place Support Fund, 1989.

Waselkov, Gregory A., Peter H. Wood, and M. Thomas Hatley. Powhatan’s Mantle : Indians in the Colonial Southeast. [in English] Lincoln: Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, c2006., 2006.

Wittenberg, Eric J. We Ride a Whirlwind : Sherman and Johnston at Bennett Place. 1999.