Impact of access and quality of health care on child health outcomes

Globally, the majority of childhood deaths in the post-neonatal period are caused by infections that can be effectively treated or prevented with inexpensive interventions delivered through even very basic health facilities. Many key health interventions, including prevention, rely on a backbone of health service delivery in order to effectively reach the target population. For example, major malaria control strategies include early diagnosis and treatment, chemoprevention of malaria in pregnancy, and distribution of insecticide-treated bednets to children attending immunization clinics or women attending prenatal care. Undoubtedly the strength of the underlying health system influences the effectiveness of these interventions, but measuring the contribution of health systems to child outcomes is methodologically challenging.

Globally, the majority of childhood deaths in the post-neonatal period are caused by infections that can be effectively treated or prevented with inexpensive interventions delivered through even very basic health facilities. Many key health interventions, including prevention, rely on a backbone of health service delivery in order to effectively reach the target population. For example, major malaria control strategies include early diagnosis and treatment, chemoprevention of malaria in pregnancy, and distribution of insecticide-treated bednets to children attending immunization clinics or women attending prenatal care. Undoubtedly the strength of the underlying health system influences the effectiveness of these interventions, but measuring the contribution of health systems to child outcomes is methodologically challenging.

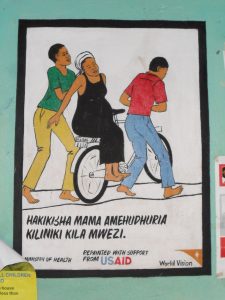

My work has shown that physical proximity to a primary health care center is associated with a >2 fold reduction in the incidence of hospitalization with malaria. Although treatment through primary care facilities is protective, population coverage with insecticide-treated bednets is unacceptably low in areas where the main distribution channel is through contact with a health facility.

We employed innovative spatial techniques and large population-based datasets to quantify the contribution of health systems to child survival. In Kenya, we explored the contribution of access, quality and cost of health services on child survival in a cohort of >80,000 children from 1996-2013. We showed that higher per capita density of health facilities reduced the risk of childhood death by 25% and that fees for sick child visits increased the risk of death by 30%. Expanding this approach, we built a cohort of 250,000 children from seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa. We analyzed the impact of health service context on survival and found again that fees for services undermined child survival – immunization fees increased the risk of childhood death by 20% and delivery fees increased the risk of infant death by 10%.

These results implicate health systems constraints in child mortality, quantify the contribution of specific domains of health services, and suggest priority areas for improvement to accelerate reductions in child mortality.

Collaborators: Rebecca Anthopolos, Ryan Simmons

Publications

- R. Simmons, R. Anthopolos, W.Prudhomme O’Meara “Effect of health systems context on infant and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa from 1995 to 2015, a longitudinal cohort analysis” Scientific Reports 11(1):16263 (2021)

- R. Anthopolos, R. Simmons, W.P. O’Meara “A retrospective cohort study to quantify the contribution of health systems to child survival in Kenya: 1996-2014” Scientific Reports 7:44309 (2017) PMC5349518

- Heng S, O’Meara WP, Simmons RA, Small DS. Relationship between changing malaria burden and low birth weight in sub-Saharan Africa: A difference-in-differences study via a pair-of-pairs approach. Elife. 2021 Jul 14;10:e65133. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65133. PMID: 34259625; PMCID: PMC8279759.

- W. P. O’Meara, A. Noor, H. Gatakaa, B. Tsofa, F. E. McKenzie, K. Marsh, “The impact of primary health care on malaria morbidity – defining access by disease burden” Tropical Medicine and International Health 14(1) 29-35 (2009)

- A. Wesolowski, W. Prudhomme O’Meara, A.Tatem, S. Ndege, N. Eagle, C. Buckee “Quantifying the impact of accessibility on preventative healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Epidemiology, 26:223–228 (2015)

- W. P. O’Meara, N. Smith, E. Ekal, D. Cole, S. Ndege, “Spatial distribution of bednet coverage under routine distribution through the public health sector in a rural district in Kenya” PLoS One 6(10) (2011).

- W. P. O’Meara, A. Platt, V. Naanyu, D. Cole, S. Ndege, “Spatial autocorrelation in uptake of antenatal care and relationship to individual, household and village-level factors: results from a community-based survey of pregnant women in six districts in western Kenya” International Journal of Health Geographics 12:55 (2013)