My Shanghainese Journey:

From the Old Alleys to “Thunderstorm”

by Vivian Zhai (Vivian)

“The dialect may soon disappear with the demolition of the old alleys,” I guessed. “We are going to lose our identity.” Still, it couldn’t deter me from learning Shanghainese – a language learning journey that would bring me into contact with figures and forms as varied as the elderly people in those alleys, a comedic Shanghai radio show host, and even a renowned opera of “China’s Shakespeare.”

· Linguistic Landscapes·

My Shanghainese Journey:

From the Old Alleys to “Thunderstorm”

“The dialect may soon disappear with the demolition of the old alleys,” I guessed. “We are going to lose our identity.” Still, it couldn’t deter me from learning Shanghainese – a language learning journey that would bring me into contact with figures and forms as varied as the elderly people in those alleys, a comedic Shanghai radio show host, and even a renowned opera of “China’s Shakespeare.”

· Linguistic Landscapes·

By Vivian Zhai

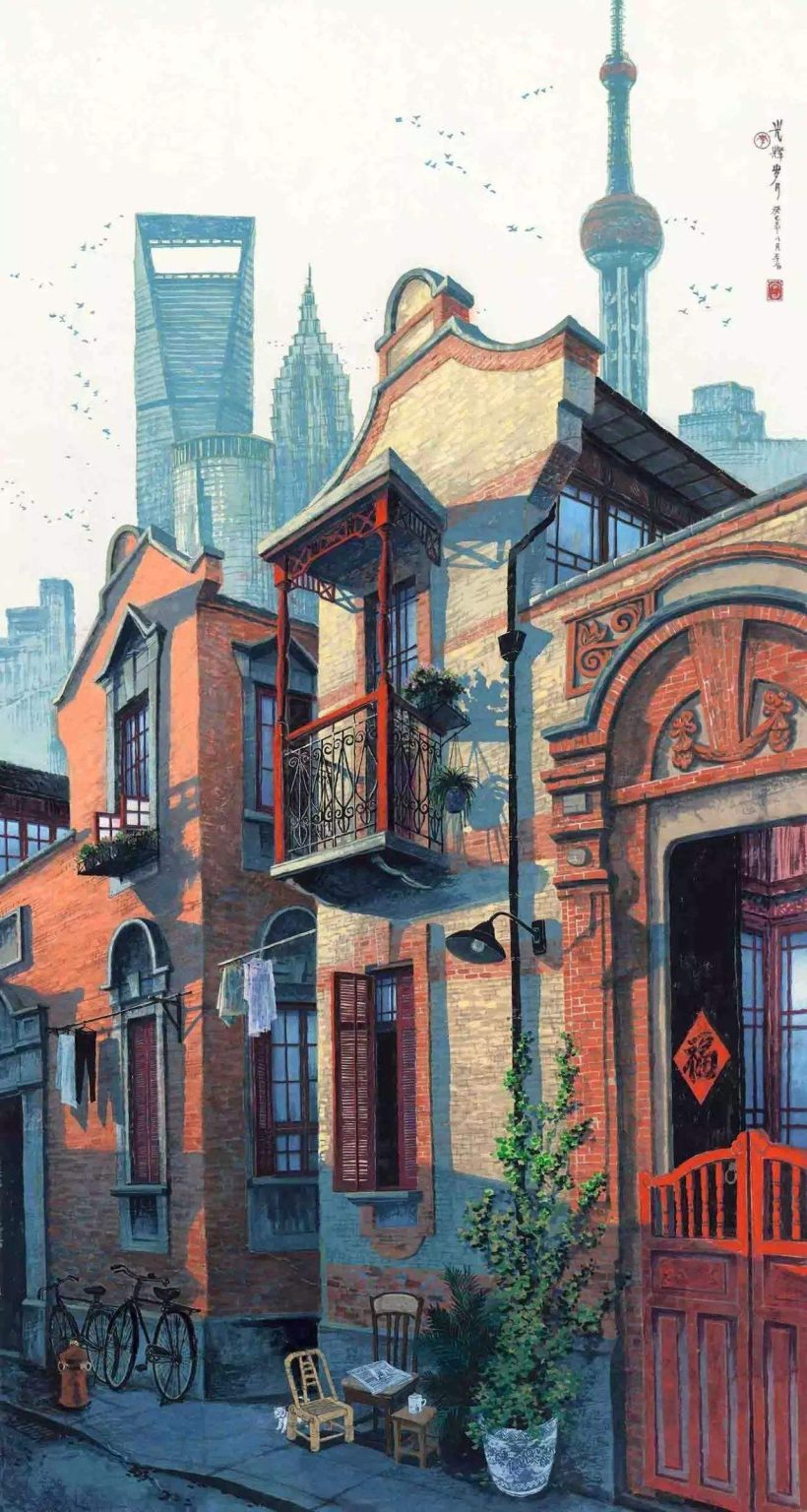

credits: https://nostalgia.org.cn/yuanchuang/48.html

I made my way through the chaotic alleys of downtown Shanghai with clothes hanging everywhere. “There’s steaming breakfast. Come and buy it!” hawkers shouted in Shanghai dialect. Compared with the flourishing skyscrapers, the alleys looked like a different world. That was one of my first impressions of my hometown language, which was related to the messy environment of “Old Shanghai.” But everything from the growing emphasis on Mandarin to the lack of interest in the dialect from the younger generation made me question the future of Shanghainese. “The dialect may soon disappear with the demolition of the old alleys,” I guessed. “We are going to lose our identity.” Still, it couldn’t deter me from learning Shanghainese – a language learning journey that would bring me into contact with figures and forms as varied as the elderly people in those alleys, a comedic Shanghai radio show host, and even a renowned opera of “China’s Shakespeare.”

Even though I am a native of Shanghai, I was the only one in my home who was not able to speak Shanghainese until I was eight. I could speak a little bit of it before I went to school. However, with the promotion of Mandarin, we were not allowed to speak it in school anymore. My memory of it gradually faded. But in my dad’s opinion, being unable to speak the dialect meant forgetting our roots. “As a native of Shanghai, the dialect is our symbol. You must learn it,” he said to me strictly. That was the beginning of my dialect learning journey.

My lesson began with daily communication. Thanks to the language environment that I was immersed in, I could understand family conversations after some time. However, speaking was a big problem. The pronunciation of the dialect was totally different from Mandarin. For instance, “ni” sounded like “nong” and “women” sounded like “ah la.” Sometimes, I felt that I was studying a foreign language. Indeed, even though I could speak a few words, I still found it hard to transform them into whole sentences. My dad called me “yang jing bang,” which refers to a person whose pronunciation is inaccurate and funny. Gradually, I got accustomed to being called “yang jing bang.”

credit: advertisements for the popular radio show “Ah Qing Tells a Story”

Things started to change when I began to help my grandma use the radio and television. She bought it to listen to and watch some programs which were all in Shanghai dialect. What impressed me a lot was a TV program called “Ah Qing Tells a Story”(阿庆讲故事). Ah Qing, the host of the show, was a well-known comic artist in Shanghai. He had a great passion for telling stories in his unique way. The program went viral among the elderly, as it told some true-to-life stories about people in Shanghai. Such us: Xiao Ming and Xiao Hua divorced because Xiao Hua was addicted to buying things online. The stories might sound boring. But what actually fascinated me was Ah Qing’s intriguing tone and intonation with the dialect – I became completely immersed in his stories. And I began to imitate his tone of voice in Shanghainese to make my grandma laugh. Gradually, as I imitated, I was surprised to find that my pronunciation and fluency got better, and I was able to have some simple dialogues with my dad.

Besides that, I also watched a lot of Huju 沪剧 (Shanghai opera) with my grandma who is a big fan of it. The classic Huju “Thunderstorm” 雷雨 written by the playwright Cao Yu – sometimes called the “Shakespeare of China” – was definitely my favorite. It told a family’s story during the Republic of China era, and how the sins of the “morally depraved and corrupt patriarch,” the wealthy Zhou Puyuan, affect his whole family. One of his sons, the eldest, Zhou Ping, fell in love with his maid, Si Feng. But the doomed lovers later discover they have the same mother, but different fathers. The wealthy father had abandoned Si Feng’s mother, his lover of the time, when she was pregnant because she was one of the family’s servants – but he kept the older of two sons she gave birth to, Zhou Ping. (The abandoned maid later married a common worker, giving birth to Si Feng.) When Si Feng discovers that she and her lover, Zhou Ping, are half-brother and sister, she runs out of the house into a thunderstorm, and Zhou Ping’s younger brother runs after her. Both Si Feng and the younger brother are killed by an electrical wire damaged from the storm. Zhou Ping, upon hearing of the death of his lover and his younger brother, gets a pistol and takes his own life. Ultimately, it is the selfishness of the wealthy father, Zhou Puyuan – who continues to live, but with shame and regret – and the darkness of that time that leads to this tragedy of two generations.

credit: from the productions of Cao Yu’s renowned tragic opera “Thunderstorm”

The tragic opera significantly raised people’s interest in Shanghai dialect culture since it was first performed at the Shanghai Grand Theatre in 1955. In the modern adaptation of the opera I watched, when I was about 12 years old, I tried to invite my friends to go to the theatre and watch it. I worked as a translator because some of my friends couldn’t understand the dialect. During the translation process, I developed a deeper understanding of the opera. It is a great work exploring feudalism, tragedy, and the inability to control one’s fate – as a number of reviews have described. “Thunderstorm” was initially thought of by many as a story about a northern family. However, on the Huju stage, it was performed in the softer Wu dialect, which transforms it into a Jiangnan (southern region) story and showcases the Shanghai style. Cao Yu, the original playwright, even remarked that of all the opera versions of “Thunderstorm,” Huju’s adaptation stands out as the best. Huju excels in performing tragic stories with strong dramatic conflicts – a characteristic of the “Thunderstorm” script – according to a review in the newspaper Guangming Ribao. Moreover, the traditional Shanghai-style costumes of Huju, specifically suits and cheongsams, add a special touch to the story. Famous Huju artist Mao Shanyu once said: “Huju possesses an inclusive temperament just like the city of Shanghai. It seems to have a kind of magic that makes these works ultimately evolve into Shanghai’s stories.”

Although Shanghai is a modern city, there is still the existence of old Shanghai behind the skyscrapers. Local people still live in the old alleys which are called “long tang.” In the evening, if you walk into these narrow lanes, you will find that time seems to slow down there. I still remember the moment when I sat next to Grandpa Cheng, a 70-year-old man who lived alone in the “Yu Yuan” alley. He enjoyed the company of children and of the neighborhood itself – making him no longer feel lonely. Under the sunset, we chatted with each other in the dialect and laughed. “Teach me how to use the new things quickly!” Cheng said. He was always curious about how to use the smartphone, and I learned a lot from his legendary stories about what had happened during the Cultural Revolution. He said that like many students of that era, he left school. For the first time, he ventured beyond the narrow “long tang” of Shanghai, taking a complimentary train to Beijing to meet Chairman Mao in Tiananmen Square.

Shanghai is a city with two sides. One is the modern side; the other is the traditional side. It is the combination of the old and the new that makes it unique. Even though Shanghai has become more and more diversified, we still can’t forget our dialect, which is our symbol and connects us to our roots. Through my journey of learning Shanghai dialect, I finally realized I had a duty to pass it down to the next generation and spread it to the broader world. Again, I was walking through the “long tang” with my family. I felt so proud of our “Old Shanghai.”

credit: www.sohu.com/a/489060962_99970508

Who is Jingwen Zhai (Vivian)?

Jingwen Zhai (Vivian) is from the class of 2027, and her intended major is psychology. She is passionate about participating in charitable events, loves exploring new places, and enjoys capturing these moments through photography. As a dedicated pet lover, she is committed to rescuing stray dogs.

Editors | Giulia de Cristofaro

Layout | Lexue Song 宋乐雪

Website | Josh Manto

credit: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/livestream-ecommerce-china/