The “How” and “Why” of Cram Schools in China

BY LI YUAN 李源

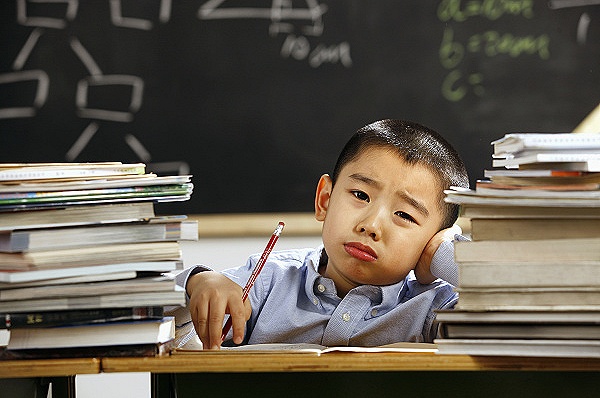

Cram schools (补习班) are everywhere in China. What lies behind their popularity?

Image credit: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201812/14/WS5c12c16da310eff303290e85.html

Image credit: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201812/14/WS5c12c16da310eff303290e85.html

Cram schools have been evolving over time. Decades ago, they were designed for laggard students who had difficulties in catching up to the pace of the traditional schools. Most of them only provided a single subject and helped students go over basic textbook knowledge. In recent years, however, they have begun to teach various subjects. Moreover, a new type of cram school is emerging, boasting that the purpose of their education is to train students’ reasoning ability (siwei 思维).

This advertising strategy proved to be a great success as many people have begun to regard it as an important supplement to traditional education. This kind of cram school is gaining further expansion with the popularity of Academic Olympics Competitions. The competition reward is a ticket to the most prestigious universities in China, and some excellent students who have no trouble grasping the basic knowledge from traditional schools will sign up for cram schools that provide systematic instruction for these competitions. Therefore, the multiple layers of the cram schools lead to the emergence of an interesting phenomenon: no matter how well students perform in school, the cram schools are their obligatory places during the weekend.

The growing popularity of cram schools leads to the transformation of students’ lives. When I was in middle school, I took two extra courses during the weekend on average. By contrast, my younger sister, currently a middle school student, has to shuttle between different cram schools all the time and her weekend schedule is packed with different supplementary courses. She takes two different math courses with different levels because she needs to not only lay a solid foundation in basic knowledge but also challenge herself in order to improve her reasoning ability. Moreover, she told me that her experience is quite typical as she sees many of her classmates at cram school. Even though she is a good student, she is still under pressure because most of the students in her class seem to already grasp knowledge that the teachers have not covered.

Image credit: https://www.jiemian.com/article/2596137.html

As a matter of fact, my sister and our parents are not alone in realizing the significance of reasoning ability. Traditionally, there are two main qualities that Chinese people value most: virtue (de德) and intelligence (zhi 智), meaning a high level of reasoning ability (siwei 思维). Virtue decides a person’s “lower bound,” namely moral foundation, while the “upper limit” depends on reasoning ability. That is, reasoning ability is a prediction of how successful a person will be. Nowadays many Chinese people believe that quantitative reasoning courses are more important than humanities courses, which only require rigid recitation for historical and political reasons. Therefore, Chinese people naturally connect siwei with science courses and this becomes many parents’ reason to send youngsters to cram schools.

In fact, parents play a more complex role in the cram school phenomenon. More specifically, many Chinese education critics who call for lightening students’ burden are the very same parents who send their children to cram schools and increase students’ pressure. Parents are in a difficult position and are ambivalent. They are reluctant or regretful sometimes as they realize that the young generation is sacrificing leisure time playing outside or participating in team sports. Nonetheless, they have to compromise as they do not want their children to lose confidence if their grades are behind others’. They understand that this competition is unhealthy, but they have no choice.

Image credit: https://www.todaysparent.com/family/how-to-talk-to-your-kid-about-report-cards/

Image credit: https://www.todaysparent.com/family/how-to-talk-to-your-kid-about-report-cards/

The boom in buxiban becomes even more surprising if you take public policy into consideration. In 2018 the government announced clear restrictions on supplementary school. [2. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, “Announcement on Regulation and Reform of Extracurricular Training Programs,” (关于切实做好校外培训机构专项治理整改工作的通, September 3, 2018, http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3325/201809/t20180912_348404.html] This contradiction raises a question: How could cram schools explicitly limited by the government still be a flourishing industry?

Constraints have been placed on the expansion of cram schools according to administrative rules; however, there is not much practical suppression. The truth is, the government also finds it tricky to solve this problem. On the one hand, there are a great number of parents and teachers crying for lightening the academic burden on students. These appeals are too prevalent to be dismissed; on the other hand, students’ and parents’ demand for various kinds of cram schools is ever-increasing and considerable. The government realizes that if they conduct real top-down control and prohibit these schools, there will be overwhelming criticisms of those policies.

This phenomenon reflects the increasing anxiety among parents. The term “helicopter parent” was first used in Dr. Haim Ginott’s 1969 book Parents & Teenagers by teens who said their parents would hover over them like a helicopter. [3. Kate Bayless, “What Is Helicopter Parenting?” Parents, December 5, 2019, https://www.parents.com/parenting/better-parenting/what-is-helicopter-parenting/] Helicopter parents are common in China and play an essential role. A large number of parents are involved in so-called peidu (陪读), meaning studying with their children. They familiarize themselves with the subjects their children are weak at and therefore try hard to find cram schools to make up for their deficiency. Also, cram schools match parents’ desire for their children to do well in examinations. Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate deeper why parents hover all the time, which illustrates the popularity of the cram schools in China.

Image credit: https://www.learningliftoff.com/new-study-has-warnings-for-helicopter-parents/

First and foremost, the anxiety stems from peer pressure among parents. The increasing competition between students in terms of grades reflects the surreptitious competition between parents. Mothers and fathers see other over-involved parents, which can trigger a similar response. “Sometimes when we observe other parents over-parenting or being helicopter parents, it will pressure us to do the same,” Dr. Carolyn Daitch, a noted psychologist points out. “We can easily feel that if we don’t immerse ourselves in our children’s lives, we are bad parents. Guilt is a large component in this dynamic”. [4. Ibid.]

Image credit: http://img.mp.itc.cn/upload/20160501/e4619cbe78f94e60bb8eb7c73cbbb0e6_th.jpg

Moreover, utilitarianism contributes to parents’ anxiety. In ancient China, it was widely believed that a good scholar would become an official (xue er you ze shi 学而优则仕). That is, having a brilliant performance in the civil service entrance examination was a common way for ancient Chinese people to become officials, thus bringing them social status and wealth. [6. Jia Ru, “Taking the Gaokao,” in My Country and My People 2019 Edition: A Brief Introduction to Chinese Culture by Members of the DKU Class of 2022, ed. Austin Woerner, (self-published, 2019), 161-165.] In contemporary China, these kinds of norms are still rooted in many people’s minds, namely that receiving admission from a prestigious university would guarantee an advantageous position in the job market. It becomes a necessity to enter a well-recognized junior and high school so that children would have access to better education resources and have a higher potential to perform better in the exams. As many middle schools have selective entry examinations, parents feel obliged to improve students’ current scores, which is consistent with the mission of cram schools. Therefore, driven by peer pressure and utilitarianism, Chinese parents push their children into fierce competition.

Li Yuan (李源) is from the class of 2023 at DKU. He is majoring in data science and is also interested in literature. He wrote this essay in Austin Woerner’s EAP 102A class, and he is delighted to examine this cultural phenomenon with you.

Li Yuan (李源) is from the class of 2023 at DKU. He is majoring in data science and is also interested in literature. He wrote this essay in Austin Woerner’s EAP 102A class, and he is delighted to examine this cultural phenomenon with you.References

- “Cram School Tuition Has Become a Major Burden for Chinese Families” (课外补习费已成中国家庭沉重负担), The South China Morning Post, December 5, 2018, https://www.zaobao.com/keywords/nan-hua-zao-bao-0.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, “Announcement on Regulation and Reform of Extracurricular Training Programs,” (关于切实做好校外培训机构专项治理整改工作的通, September 3, 2018, http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3325/201809/t20180912_348404.html

- Kate Bayless, “What Is Helicopter Parenting?” Parents, December 5, 2019, https://www.parents.com/parenting/better-parenting/what-is-helicopter-parenting/

- Ibid.

- Guo Qi, “Giving Kids a Head Start,” in My Country and My People 2019 Edition: A Brief Introduction to Chinese Culture by Members of the DKU Class of 2022, ed. Austin Woerner, (self-published, 2019), 149-154.

- Jia Ru, “Taking the Gaokao,” in My Country and My People 2019 Edition: A Brief Introduction to Chinese Culture by Members of the DKU Class of 2022, ed. Austin Woerner, (self-published, 2019), 161-165.