Meet Christine Markwalter! She is one of the postdocs working with the O’Meara Lab and has been a member of the greater malaria research community at Duke for 3 years. Christine came to Duke after completing her doctoral studies at Vanderbilt University in chemistry. She is currently focused on a project analyzing haplotypes from mosquitos and humans that are a part of the Once Bitten cohort study, as well as some haplotype data from our Turkana project.

So how did Christine end up studying malaria in Kenya with a PhD in chemistry, you might ask?

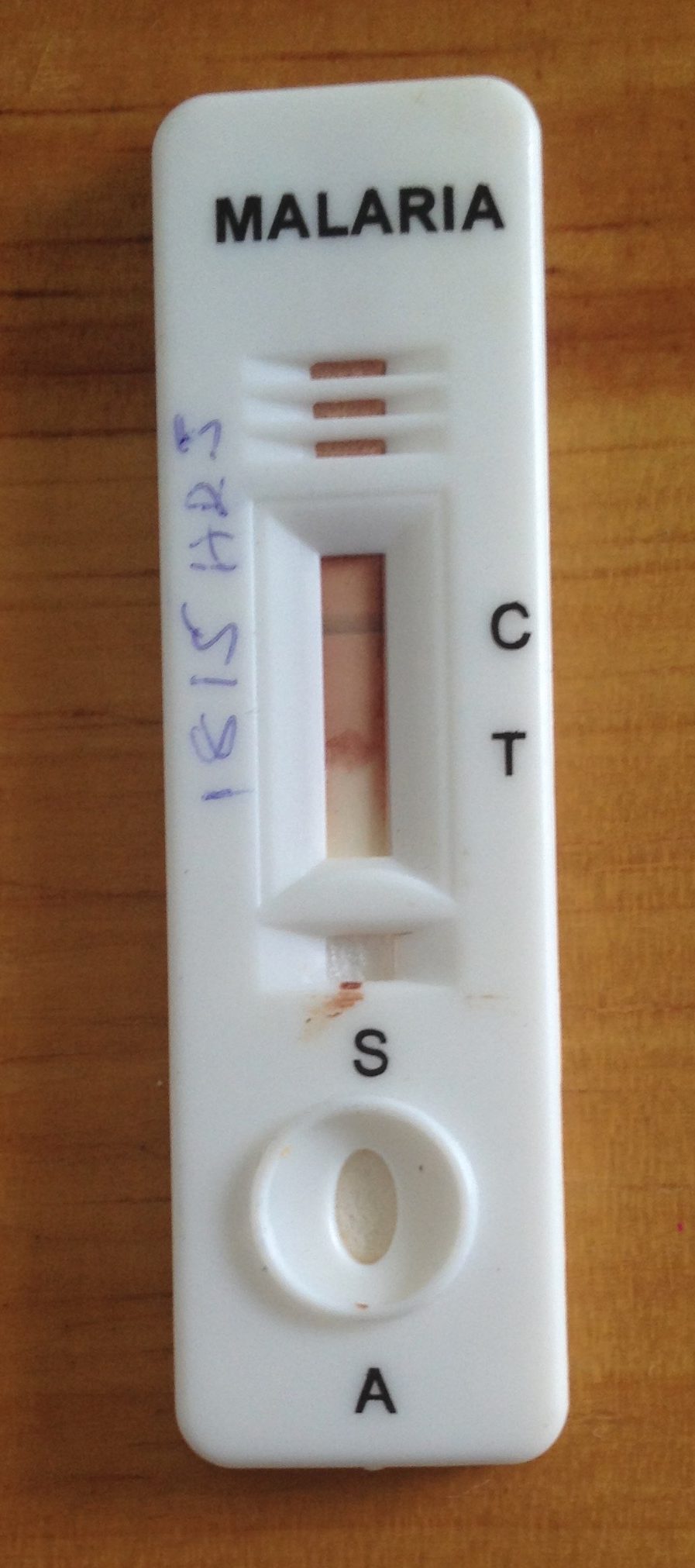

Well, by way of bioanalytical chemistry, actually. For her doctoral work, Christine was investigating how to make rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) more sensitive in order to detect lower density infections, specifically for malaria and schistosomiasis. After she finished her PhD studies in the lab, she decided she wanted to gain more epidemiology and field work experience, which is what ultimately landed her in the Malaria Collaboratory at Duke.

This past summer, Christine was able to spend 3 weeks in Kenya. This was her first trip visiting the field site there, and her trip started off with the ever-eventful loss of luggage by the airline. Normally this wouldn’t have been a huge deal for a seasoned traveler like Christine, but this time she was traveling with her husband Daniel, an Emergency Medicine fellow at UNC, and their baby daughter Ellis. Thankfully they had packed most of baby Ellis’ items in their carry-on’s, but the first day or two in Eldoret were spent going back and forth to the local mall to get spare clothes and supplies.

The ExactDx team, in true harambee fashion, did their best to help Christine and her family settle in sans luggage. On the way from the airport to retrieve their suitcases a few days later, Edna and Julius thought it would be fun to give Christine and Daniel a taste of traditional Kenyan cuisine. They stopped off and treated them to some nyama choma (grilled goat meat) and ugali. The meal remains a favorite from their visit, and Christine and Daniel cannot wait for their next opportunity to enjoy delicious Kenyan cuisine.

After a week of orientation in Eldoret, meeting with different team members in person, including some collaborators at Moi University, Christine and baby Ellis headed out to Webuye to experience a day of “ento.” “Ento” is short for “entomology” and refers to the days when field researchers (FRs) strap on their prokopacks and visit each of the households enrolled in the Once Bitten study to collect mosquitoes. The days begin early, usually around 6 am. This is the optimal time for catching mosquitoes in the households where they have potentially bitten members during the night. Household members are asked to keep windows and doors closed until team members arrive for mosquito collection.

“I was blown away with how generous the study participants are, letting the study team into their homes to collect the mosquitoes so early in the mornings. To me that is typical of the Kenyan hospitality I experienced throughout my trip,” recalled Christine.

Christine enjoyed getting to use the prokopack and helping collect some of the mosquitoes whose bloodmeals she’ll ultimately end up analyzing in the US. She was able to spend the afternoon with the FRs back at PEARL where she observed them sort species, rear, sacrifice and dissect the mosquitoes. The team places the mosquito parts (head, wing, and abdomen) in pre-labeled eppendorf tubes and package them by household and village before shipping them to the Taylor lab in the US. Once in Durham, members of the Taylor lab receive the mosquito parts (heads, wings, and abdomens) and processes the mosquitoes further, extracting and sequencing parasite DNA for analyses. This field visit provided Christine with knowledge and insight about the context and environment from which samples are collected, and will give her a richer understanding as she conducts her analyses and thinks about the team’s scientific questions.

In addition to gaining invaluable field experience, Christine volunteered some of her laboratory expertise at PEARL to help get a mosquito PCR speciation assay up and running. One difference she noticed between the lab set up in rural Webuye compared to Durham was the impressive amount of planning and forethought required to keep things running smoothly in the lab. At Duke, if a reagent runs out or if she runs into a problem with an instrument, she can just make an online order for next day delivery or take advantage of the many resources and experts available on campus. When challenges arise in the lab in Webuye, the team approaches them with creativity and careful planning, keeping a detailed inventory log so that orders can be placed months in advance. Christine was impressed by the molecular assays and techniques the PEARL team performs, and she is excited by the lab’s potential to do more as the program continues to grow there.

Christine also facilitated the monthly CME course for July, which is part of the many training activities that are conducted out of PEARL. Her topic was diagnostic technologies and she went over the advantages/disadvantages of different formats (rapid tests, PCR, antibody detection, etc.). The topic was very timely given the recent discussion globally around COVID-19 diagnostic methods and was attended by clinicians and researchers at PEARL and virtually.

She wrapped up her trip in Eldoret working with some other expat collaborators who were fortuitously visiting our office at the same time (a rarity during pandemic times!). She and her family are so grateful to have met the ExactDx team in person and for their genuine hospitality and care. They are already looking forward to returning! Karibu!

This week, the

This week, the

We were delighted to host Chris Plowe (DGHI Director), Eugene Washington (Chancellor), Chris Tobias (DGHI Director of Finance and Operations) and Jamie Mills (Grants and Contracts Manager) to Eldoret this week! We were able to introduce them to the wide range of collaborations and initiatives in Eldoret and most importantly introduce them to our partners here at Moi University. They were able to visit the Cardiac Care Unit at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, a group of peer counsellors working with Eve Puffer’s team, and visit our community-based cohort in Webuye, Kenya.

We were delighted to host Chris Plowe (DGHI Director), Eugene Washington (Chancellor), Chris Tobias (DGHI Director of Finance and Operations) and Jamie Mills (Grants and Contracts Manager) to Eldoret this week! We were able to introduce them to the wide range of collaborations and initiatives in Eldoret and most importantly introduce them to our partners here at Moi University. They were able to visit the Cardiac Care Unit at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, a group of peer counsellors working with Eve Puffer’s team, and visit our community-based cohort in Webuye, Kenya.

Dr. Plowe and Dr. Washington learning the finer points of identifying mosquito species by microscope

Dr. Plowe and Dr. Washington learning the finer points of identifying mosquito species by microscope