James Joyce Scrapbook: Forget About Dublin by Sara B.

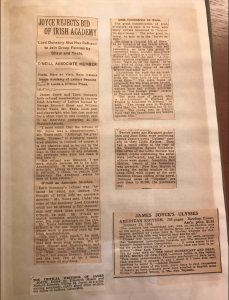

As I opened the large, light green book filled to the brim with articles and news clippings about James Joyce, it was impossible not to be completely overwhelmed by the pages filled edge to edge. As I flipped through the book, the main thing that stood out to me was how the articles were mainly from American publications, such as The Saturday Review of Literature and The New York Times. This surprised me because of how much we discussed Joyce’s works being rooted in Ireland; I would have been much less surprised to see a scrapbook like this comprised of Irish reviews.

Looking at all of the American reviews, especially those revering Joyce, made me reconsider the idea of city in Dubliners. In the short story “Araby”, Joyce describes the journey of a boy who wants to impress a girl by buying her a gift from a market. The boy spends all night traveling, but is disillusioned when he sees the market in person. Joyce mentions several places in Dublin, such as North Richmond Street, Buckingham Street, and the market Araby. However, if the proper nouns are all taken out of the story, it’s hard to find proof that it is specifically taking place in Ireland. There is also very little about the characters that make them uniquely from Dublin. It could just as easily have occurred in England, in mainland Europe, or even in America.

Because the work was so resonant in America, I propose a reading of “Araby” not focused on city but on character. The collection is called Dubliners, not just Dublin; instead of reading into how the characters are molded by the city, I’m interested in thinking about how the characters mold the city around them. Through this reading, the characters can be given more autonomy– rather than simply being the product of their environment, they have personality types that can be seen in people all over the globe. The scrapbook shows that these characters are relatable to people everywhere. I believe the story is powerful because of the dynamic and relatable characters, regardless of their setting.

This theory is exemplified in the two ways we can read the ending of “Araby,” the boy’s disillusionment. The first is through the lens of how the city shapes the story. The boy is tired and cranky mainly because he’s had an exhausting adventure. The train was confusing and frustrating, and his travels have taken a toll on him. The second is through the lens of how the characters shape the story. The boy is not sad because of his physical environment, but because this is a traditional bildungsroman, or coming of age story. If we focus on the first interpretation, we see how the city of Dublin is layed out, how a boy would travel across town, and how he interacts with his family. It is a more analytical and factual reading. The second reading, though, is much more emotional and relatable. We can see direct connections to our own lives, and the story can influence our actions, regardless of our physical location. Though both interpretations have a basis in the text, the carefully crafted scrapbook leads me to believe that the second one is more powerful. Americans, across the ocean from Ireland, were able to relate to this story. The majority of them couldn’t have related to the setting of Dublin, but they related to the story of a boy who tries to impress a girl.

I think it’s really important to remember that although this class is focused on Eurpoean fiction, the stories we’re reading must have a universal impact, and we must search for meaning beyond Europe. We must remember that these works have maintained their relevance through time for a reason: because they are independent of time and space. Through this perspective, it’s much more easy to place ourselves in the shoes of the young boy in “Araby”.

Recent Comments