Starring or Merely Featuring Katherine Mansfield’s Works?: An Examination of “Atalanta’s Garland” by Storey W.

I examined a first-edition copy of Atalanta’s Garland, a book published by T. and A. Constable Ltd. in 1926 to celebrate the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the Women’s Union at Edinburgh University. A medium-sized hardback book, Atalanta’s Garland is accessible; it can easily be held in one hand and flipped through like a typical novel. The prefatory note in this work elucidates that Atalanta’s Garland was composed to honor the achievements and strides made by women throughout the 20th century. The target audience seems to be young women, for the works contained within are meant to be empowering. The prefatory note continues that women were first admitted to Edinburgh University in 1892, but by the time this book was written in 1926, hundreds of women had matriculated and made significant contributions to the worlds of education, civil service, and the arts. Comprised of an amalgam of short stories, poems, and illustrations from various contributors (including Katherine Mansfield, Virginia Woolf, H. Belloc, W.H. Davies, T.B Simpson, and many others), Atalanta’s Garland “illustrate[s] woman’s art in the short story of today.”

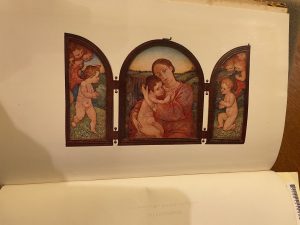

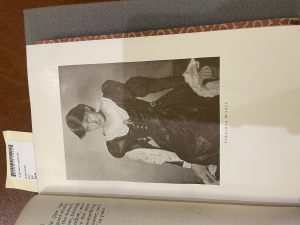

Atalanta’s Garland contains a frontispiece called “Motherhood” by Pheobe Traquair. This illustration depicts a woman embracing her child in the center, while in the wings, two circular enamels depict references to “Eve and the Serpent” and “Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.” This is an interesting choice for the frontispiece of a feminist work, for Eve is not typically a feminist symbol. However, this frontispiece may be fitting for a work that celebrates the role of women because it romanticizes the seemingly mundane aspects of motherhood. Although the mother appears to simply holding her child, angels are peering down on her from either side, making the act of motherhood take on an almost holy air. There are dozens of other beautiful illustrations within this work, including various portraits of authors featured within the collection.

Although this book contains works from dozens of authors, a House of Books listing tucked into the front of the book advertises it as “[Mansfield] Atalanta’s Garland. Also contributions by Virginia Woolf, Walter de la Mare, and others.” I found it curious that, although Mansfield’s stories take up a mere six pages, this book is framed and advertised as primarily featuring the work of Mansfield. This is potentially due to the fact that Mansfield is considered one of the most influential modernist authors of all time, so the fact that this book features her unpublished works is noteworthy and worthy of promoting. Although Atalanta’s Garland is characterized as “starring” Mansfield’s work, in reality, it seems to be that Mansfield is just one of dozens of authors featured in this work.

Two “unpublished sketches” by Mansfield are only available within Atalanta’s Garland, and these pieces are contained at the beginning of this work. They are titled “Little Jean” and “Lucien” and were the opening paragraphs of stories that Mansfield began but never finished. Middleton Murray, Mansfield’s husband (who was also a prolific author and the publisher of 60 books), granted the publishers permission to print these sketches.

“Little Jean” and “Lucien” are studies of two French children. The first sketch, “Little Jean”, was written in 1922, one year prior to Mansfield’s death. This story begins to tell the tale of a mother caring for her young child. This story details how Jean’s mother hopes others will take note of and acknowledge the sacrifices she has made as a mother, but ultimately, everyone is so preoccupied with their own lives that they do not pay her any attention. Meanwhile, “Lucien” is the story of a young boy who is “not like other boys” because he does not have a father and does not attend school. His mother, a dressmaker, recruits him to help work and deliver newspapers around town.

Although these sketches are brief and incomplete, they are still powerful works that bear similarities to Mansfield’s “The Garden Party.” “The Garden Party” is a story in which the wealthy Sheridan family commences the preparations for a lavish party (they set up a marquee, order flowers, bring in a piano, etc.) However, when their neighbor is killed right outside of their home, one of the daughters, Laura, debates whether they should call of the party. Her family ridicules her for concerning herself with matters of the lower class, and they carry through with their plans to host the party, which is ultimately a grand success. At the end of the story, Laura visits the late man’s house and is overcome with emotion when she sees his corpse.

All three of Mansfield’s stories explore the themes of class. Mansfield writes that Little Jean’s “cheeks are white because he lived in a basement,” insinuating that he and his mother are poor and isolated. Meanwhile, Lucien’s mother “rummaged” in the folds of her petticoat to pull out a “shabby purse” in search of coins. “The Garden Party” contains characters from various social strata; many of the wealthier characters view themselves as superior to the characters who live in “poverty-stricken” “eyesore” establishments, and Laura struggles to reconcile her superficial family values with her own empathic viewpoint. Both “The Garden Party” and “Little Jean” also contain a sense of epiphany–Laura has an epiphany when she realizes the poor old man who she looked down upon seems so happy and content (even in death), while Jean’s mother has an epiphany that the things that may seem important to her do not matter to the rest of the world. Virginia Woolf also appears in this collection with a work entitled A Woman’s College From the Outside. This short story touches on similar themes of class struggle and upward mobility–the protagonist Angela’s poor parents send her to a women’s college in hopes that she will gain an education and move up in society. Although the female protagonists in many of these works are flawed, they are all navigating the complexities of sexist and classist societal expectations. As a result, many of these women attempt to fit into the molds that society has laid out for them. Putting these works in a feminist text demonstrates that there is no singular, “right” way to be a feminist; many women are merely trying their best and that is enough.

Interesting, well-orchestrated, and meaningful, Atalanta’s Garland puts many classic authors in conversation with each other to create a powerful feminist narrative. I hadn’t previously examined Mansfield’s works via a feminist lens, but reading her stories in the context of Atalanta’s Garland cast them in a new light. When I saw that this book was compiled by college students to celebrate the anniversary of a women’s union, I was anticipating a scrapbook-style zine. This book exceeded my expectations and contains countless beautiful pieces within it.

Recent Comments