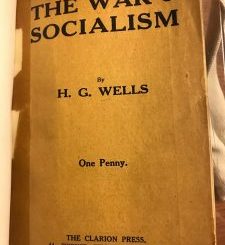

“A Dream of Armageddon” – Envisioning Dystopia Through the Lens of H. G. Wells by Ioana L

The Door in the Wall and Other Stories is a collection of eight stories by H. G. Wells, published in November 1911, which also included photographs by Alvin Langdon Coburn. This particular copy was published by Mitchell Kennerley and printed in Baltimore, MD. The manuscript was set and bound by Village Press in New York. The cover is a dark burgundy with gold lettering on the front, however, the spine was left a simple grey. This copy was one of 600, printed on thicker-than-average French paper, and is about 18 by 12 inches. One can tell this book was a gift, probably from one American to another, because on one of the first inside pages there is a dedication marked for Christmas 1911. Due to this dedication, its size, its craftsmanship, and somewhat limited printing, one could assume this book was meant to be enjoyed as a special gift, rather than as a book that could be easily opened and read lounging. It was most likely also owned by someone of the middle to upper class and probably someone who enjoyed the newer genre of science fiction and H. G. Wells.

All eight short stories in the collection fit into the genre of science fiction, and, generally, they involve themes of dystopia, machine worlds, and death. The namesake for the collection, “The Door in the Wall,” features the same story-telling dynamic as “A Dream of Armageddon.” In it, one friend recounts the life of a successful politician, who as a young boy in London, walked through a green door to find a magical garden on the other side. In the garden, a book contained the story of his life, but it stopped at the moment he reached the green door. The boy says he never experienced such happiness as when in that garden. Throughout various “career-changing” moments in his life, the boy finds the door but is unable due to time or obligations to visit the magical garden again. He is consumed by the fact he’ll never find happiness, even though he is a successful politician and businessman. He dies at the end of the story by walking through another opening in a wall and falling into an excavation site, presumably trying to walk through the green door.

In both “The Door in the Wall” and “A Dream of Armageddon,” Wells chooses to recount from a third-person point of view as if someone is recounting an already lived experience directly to the audience. It is an interesting choice on the author’s end to remove the reader from the experience in both stories. The act of story-telling gives the occurrences a more fantastical nature, even though the reader quickly learns the stories are not about utopian cities, but are, in fact, dystopian. “The Door in the Wall” thus sets the tone for the collection, which “A Dream of Armageddon,” the third short story in the work, picks up and enhances through its imagery of war and machinery disturbing the paradise of Capri. Furthermore, the works are not arranged by date of publication. For example, “The Door in the Wall” was published in 1906 in the Daily Chronicle while “A Dream of Armageddon” was published in 1901 in the magazine Black and White. Other collections of Wells’s work from 1911 rearrange the order of the stories; the first collection in which “The Door in the Wall” appeared in was titled The Country of the Blind and Other Stories. “The Country of the Blind” is the eighth story in this particular book. Overall, the stories are not necessarily meant to be read in order, but all of them work together in a collection. They all are centered in a European world, typically in England or with some relation to England (possibly the North in “A Dream of Armageddon”). They all are easy and quick to read, but surprisingly thought-provoking.

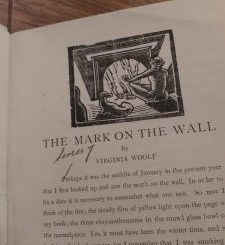

While one cannot find semantic differences between this 1911 edition and the version from class, the most exciting feature of this book is Coburn’s photos which accompany each story. For “A Dream of Armageddon,” there is a black-and-white photo of Capri. One can see a couple of villas and large houses towards the bottom of the image, steep cliffs, narrow beaches, and two big boats in the bay. This possibly is the view the dreamer and his wife would have had when looking out of their room’s window toward the west. If anything, the image is exotic looking, especially to a city audience, and helps readers imagine Pleasure City, even if in reality there are no floating palaces in Capri. Throughout the entire collection, the images ground the readers’ imagination, allowing them to build a complete visualization around what Coburn photographed and matched with each story. While the image of Capri evokes sentiments of serenity and utopianism in the readers, other images, particularly a rather dark one of a man crouching before a colossal piece of mechanical equipment in “The Lord of the Dynamos,” challenge the reader to reflect on whether society today has indeed become dystopian. Altogether, the collection makes a commentary on the way society is progressing, which is more palatable when expressed through the genre of science fiction.

Recent Comments