While one may think “The Nightingale and the Rose” is the ultimate fairy tale for hopeless romantics, it turns out to be a tragically realistic story in which the guy, unfortunately, does not get the girl.

For those unfamiliar with the work, the story opens with a boy, the “Student”, who is distraught because there is not a single rose in his garden. This symbol of love is the only way he can get the girl, the “Professor’s” daughter, to attend the dance with him. A nightingale sees his anguish, and believing in true love, sets off to get him a red rose. The bird must sacrifice itself for the Rose-tree to produce the flower. After, the bird gives its life away, the boy approaches the girl with the rose and is rejected. Unfortunately, she received more enticing offers from another boy, and the story ends with the Student swearing off love forever.

I was quickly swept through the vivid and fantastical plot while reading the Oxford World’s Classics rendition of “The Nightingale and the Rose” in part due to its formatting. This version was printed on just six pages within a larger collection of stories. Given the smaller margins, text size, and unintentional page breaks the reader is not led to form as deep of analyses or connections as they are in other versions.

Alternatively, in 1927, The Windsor Press printed 400 copies of “The Nightingale and the Rose” as a stand-alone story. This small book (approximately 5 by 8 inches) conveys the story over the course of 20 pages, inevitably causing the reader to slow down. On multiple occasions I was compelled to give pause and reflect before turning the page. As a result, new details and themes emerged from the text. The Windsor Press version also included illustrations and aesthetics specifically chosen for this story. These tailored details such as the style of the Student’s clothes (especially his shoes), the rose, the dead tree, and the title’s gothic font emphasize the story’s fairy-tale qualities.

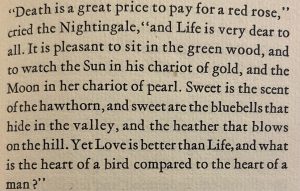

Furthermore, the intentional formatting of The Windsor Press version, emphasized the fable or fantastical elements of Wilde’s story. The first time I had read the story I took note of the more obvious personification of the trees, other plants, and animals. However, there were many other common nouns turned proper that I noticed while reading the rarer version. The space and attention drew me to the conversation around these proper nouns. Take for example the below passage (found on page 81 of the Oxford version) which personifies “life”, “sun”, “moon”, and “love”:

Prior to reading this version, I had taken the paragraph at face-value: the rationale for the Nightingale’s self-sacrifice. However, there is another level of complexity added by the personification. How and why did Wilde assign the genders that he did throughout the story?

I argue that the genders create juxtaposing groups to question and/or emphasize the connection between gender norms, idealism, conditionality, and societal reality.

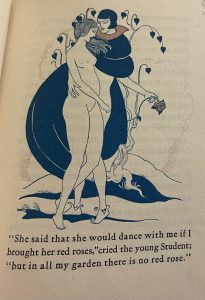

The story’s opening image conveys these gender stereotypes and primes readers for the central role that gender will play. On one side the woman is highly sexualized, depicted fully nude, with her hair long and undone (a historically sexual representation), and her child-bearing features emphasized. On the other side, the Student is seen in a position of control, fully clothed and guiding the girl. With the inclusion of this illustration, gender is placed at the forefront of this version while the role it played in the Oxford University Press edition was more nuanced. The dichotomy between this image and what unfolds in the story is also rather ironic.

Additionally, the text itself reinforces the gender considerations. The Nightingale, Moon, and Philosophy are all described using female pronouns while the Sun, Oak and Rose trees, Love, and Power are male. Notably, Life is one of the few proper nouns described with ambiguous pronouns. The Nightingale embarks on her mission to create the red rose at night and her “last burst of music” is heard by the Moon which “lingered on in the sky” (Oxford University Press, 83). After the Student is rejected in the daylight by the daughter of the Professor, he decides that he will forget Love and focus on Philosophy. The girl rejected him for the “Chamberlain’s nephew” because he has status, wealth, and offered her jewels (Oxford University Press, 83-84). In addition to gender, the role that titles and status play in society more broadly are also represented in this story.

Generally, the male nouns relate to deceit and the performative nature of society. Meanwhile, the female nouns embody unwavering hope regardless of evidence. However, the male Student was the hopeless-romantic, determined in his endeavors to win the girl, while she deceived him and gave into society. This role reversal where the male is rejected and hurt by the female could be a rejection of gender stereotypes, a comment on unexpected outcomes, a cynical view of love, or a general dislike and distrust of women.

Emphasis on the Illustrations:

Recent Comments