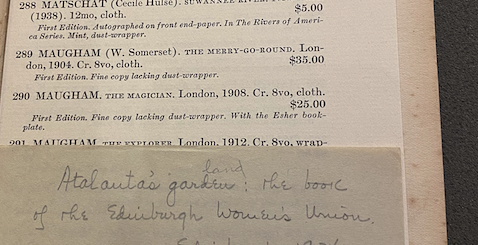

Meaning(lessness) Lost in Lithography and Translation in a French edition of Sartre’s “Le Mur” by Donald P.

I examined a 1965 French edition of Sartre’s “Le Mur,” published in a collection of other stories by Sartre (in fact, the collection was also titled Le Mur), in an imposingly large tome. In “Le Mur,” three prisoners of—Juan, Tom, and Pablo—are taken captive by the fascists in Civil War Spain and are sentenced to death. They then spend the night contemplating mortality and existence. Pablo, however, in a cruel twist of fate, is able to avoid death even after his ordeal. The French text seems better able to convey the sense of Sartre’s existentialism than the Lloyd Alexander translation that we read. This is partly because of two original lithographs by Walter Spitzer, one before the story and one in the middle, and partly because of various gaps in Alexander’s translation.

The first image, recorded below, seems to display Sartre’s metaphorical wall. Three people appear as shadows, shrouded behind hazy, ethereal concrete. On the lithograph, there are three phrases written in Spanish—the first two translate roughly to, “[They] will not pass” and “Long live freedom.” I am not clear on what exactly the third phrase says. These phrases likely refer to the anarchist resistance in the Spanish Civil War. At first, these phrases appear to be windows through the concrete haze—the wall—but on closer inspection they appear to cast shadows, indicating that they are actually projected in front of the wall. Thus, the wall functions as a barrier between the people behind it and the greater meaning in front of it. Based on the story, the wall then seems to represent awareness of mortality—it is this awareness that renders Pablo unable to comprehend his political movement’s ideals, his love for his friends and for life.

The second image, below, displays three figures huddled together in a small circle of dim light, while the rest of the image is utterly shrouded in darkness. The first two figures are likely Juan and Tom, as they are shivering while the third, Pablo, seems unfazed. Additionally, the first figure is smaller than the other two, suggesting it to be Juan, but is also emptier seeming than the others. This is in line with Pablo’s reflections on Juan’s inability to fully comprehend death due to his youth. In fact, if we understand existentialism as the absence of external meaning, then it becomes clear that the darkness surrounding the three figures is meaninglessness itself. Because Pablo and Tom are fully aware of their deaths, that meaninglessness has infiltrated their very being—that is why they are colored darkly, and Juan is not. However, the darkness can be seen to creep up Juan’s legs, suggesting that he would inevitably succumb to it as well.

Beyond the lithographs, I will discuss the language of the story itself. I will mostly focus on the ending of “Le Mur,” but first I want to discuss a feature of the French that pervades the text and that I don’t think is, or can be, properly translated. This is the French pronoun “On.” In spoken French today, it is an informal way of saying “we,” but in writing it refers to a general third-person perspective—a bit like “one,” “someone,” or “anyone” in English. It is an anonymizing and vague pronoun. Consider the opening line of “Le Mur”: “On nous poussa dans une grande salle blanche….” Alexander’s translation is “They pushed us into a big white room….” Here, “They” captures the vagueness of “On,” but not quite its generality. The use of “On” here renders Pablo’s captors in a kind of shrouding anonymity—they could be anyone, their identities do not matter. Importantly, Sartre uses “on” in this way throughout the entire story.

A second interesting use of “on” occurs when Pablo is reflecting on his life and realizing that it has lost all meaning. The sentence “But I couldn’t pass judgement on it; it was only a sketch” originally reads as “Mais on ne pouvait pas porter de jugement sur elle, c’était une ébauche.” Sartre does not use “je” (meaning “I”). This sentence might be more truly translated as “But no one could pass judgement on it, it was a sketch.” The use of “on” suggests a deeper realization of meaninglessness; Pablo perceives the incomplete, sketch-like quality of his life as observable to all people. That Pablo feels that not a single person can find substance in his life deepens the reader’s understanding of Pablo’s dissociation from himself.

In the last few pages of “Le Mur,” there are a few interesting gaps in the translation that I will comment on. The first two are smaller in importance, while the third I believe to be quite important.

On page 15 of the translation, the text reads “I saw through all their little schemes….” The French reads:

![]()

The main difference here is the word “manèges.” It can be translated as “schemes” or “ploys,” but it can also refer to a “game” or even to a “merry-go-round.” These connotations are lost in the English “scheme.” In fact, while “scheme” can connote something quite serious and intentional, the word “manège” suggests that Pablo is projecting a great childishness onto the soldiers’ behavior.

On page 16 of the translation, the text reads “And a droll sort of gaiety spread over me.” The French reads:

![]()

The verb “envahir” is quite different from the English “to spread over.” “Envahir” can mean “to invade” or “to overrun,” as in an infestation. It is a much more active and concerning for something to “invade” someone. This suggests strongly that Pablo is losing, or has lost, his self-control. It may also suggest that he has become dissociated even from his emotions—he cannot comprehend why or how he feels. His sense of identity is diminishing to an ever smaller blot.

In the last sentence of “Le Mur,” the translation reads: “Everything began to spin and I found myself sitting on the floor: I laughed so hard I cried.” The French is:

The final clause might be more literally translated as “…I laughed so hard that tears came to my eyes.” The difference here is one of control—just as Pablo cannot control his emotions, he is no longer even able to control whether he cries. The English translation’s use of active voice allows for the possibility that Pablo has regained some control over himself, that some sense of himself has been restored to him, upon discovering that he will live. But the original French does not—Sartre could have written “je pleurai” (“I cried”) if he wished to suggest such an optimistic ending. But Sartre lent Pablo’s tears the agency in this situation, establishing the finality, and possible permanence, of Pablo’s loss of himself.

My translations are possible due to the use of the Collins and the Cambridge French-English dictionaries.

Recent Comments