Albert Camus “Speech of Acceptance Upon the Award of the Nobel Prize for Literature • December 10, 1957” by Bryce G.

As the title implies, this work is a written account, translated into English from the original French, of the speech famous philosopher, artist, writer, and dramatist Albert Camus delivered after being awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1957. The piece can best be described as a pamphlet or booklet, only comprising 14 pages and being physically much smaller than a typical book, maybe only a few inches larger than a notecard. What’s notable about the object is that the form of the piece (a very small, handheld pamphlet only around a dozen pages) is not how the material was actually meant to be consumed, nor was it compiled by the original author. Unlike most of the other objects people were tasked with analyzing that could be better described as “authentic” ways the original audience would have consumed the works, this pamphlet is obviously a derivative of the original speech and, in my opinion, doesn’t add any additional significance versus an online copy or a recording of the speech. I think studying the form or “framing” of this specific piece is missing the point of why it’s worth analyzing and therefore more attention should be given to the content and context of this speech and how it relates to Camus’s broader life and the themes he conveys in “The Adulterous Woman” than the details of the physical book itself.

While the initial audience of this speech may have been the selection committee for the prize he had just won – The Nobel Committee for Literature – it is clear that Camus had written this speech for a much broader audience: all people who create art. In this vein, Camus spends the majority of his acceptance speech providing insight into his motivations and the incredibly unique responsibility artists have, particularly in the past half-century in Europe. To Camus, art is something that he cannot live without, but at the same time something that is not to be put above other things in life: indeed, he sees art as something which “excludes no one” and “is a means of stirring the greatest number of men by providing them with a privileged image of our common joys and woes.” Camus doesn’t write because he seeks affirmation or validation from the foremost literary critics – he even speaks about the sense of imposter syndrome he feels as a man “possessed only of his doubts and of a work still in progress, accustomed to live in the isolation of work or the seclusion of friendship” who receives such a sought-after award while “other European writers, often the greatest among them, are reduced to silence” – but because it is an artist’s calling two obey “the service of truth and the service of freedom.” In the face of impending nihilism, the previous “twenty years of absolutely insane history” has evoked in the generations who have had to deal with the fallout of the two world wars, artists are tasked with bringing humankind together and joining the countless other fighters in continuing our shared history and saving the world from destroying itself.

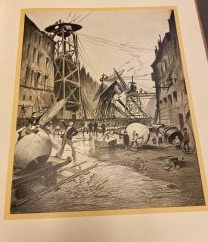

It is in this context that Camus wrote “The Adulterous Woman”. While the story doesn’t necessarily describe any morally bad behavior (this is likely up for debate), Camus seeks to fulfill the artists’ responsibility to explore the shared emotions of envy, love lost, jealousy, self-pity, and lust through the story of Janine and Marcel. The biggest question I was left with after reading this object was why, given Camus’s obvious disdain for the effects of the two World Wars on Europe, Camus chose to include a soldier as the primary temptation in “The Adulterous Woman”. While soldiers are perhaps typically seen now as agents of order and stability (at least in certain parts of the world), they had represented significant turmoil, pain, suffering, and control the previous decades in Europe, a theme Camus echoes in most of his speech. In many ways, soldiers represented the opposite goals of the “artist” Camus lays out in his speech: to destroy liberty, to drive men apart, foster nihilism, and “destroy the world”. I had several ideas for why Camus would have chosen a soldier for this piece (they represent raw masculinity, Janine’s desire to be controlled, a historical artifact of the setting the story took place in, a possible Biblical allusion, or no additional significance), but I didn’t find any of these explanations to be consistent with both the story and the speech he gave the same year the story was published.

Recent Comments