Katherine Mansfield and the Atalantas in Art by Anonymous

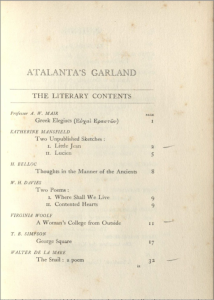

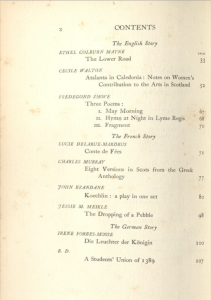

I looked at Atalanta’s Garland: Being the Book of the Edinburgh University Women’s Union in conversation with Katherine Mansfield’s “The Garden Party.” As the prefatory note of the book details, Atalanta’s Garland was published in 1926 to celebrate the twenty-first anniversary of the founding of the Edinburgh University Women’s Union and to serve as a fundraising effort for the union (v). To assemble the collection, the editorial committee sent out “an appeal…to the friends and well-wishers of the University to come to the assistance of the Union,” and this “Miscellany,” as they call the book, came to represent “the response of Art and Letters to that appeal” (v). Mansfield is in the company of a wide range of writers, poets, composers, and illustrators whose inclusions don’t all seem to follow one clear-cut rationale. The artists include men and women, individuals from both Scotland and elsewhere in the world, alumni of the university and not. The works contributed by each artist range from being explicitly about women, women’s art, or the arts in Scotland to being, on first glance, about entirely unrelated themes. This raises the question of why the committee requested a work of Mansfield’s to include, and why “two studies of French children…the opening paragraphs of unfinished stories” were the ones selected (Atalanta’s Garland 2).

While the editorial committee for Atalanta’s Garland never noted an explicit reason for their selection of these two sketches of Mansfield’s, they did describe their reasoning for some other inclusions in their miscellany. In the prefatory note, the editorial committee writes that the title “Atalanta” was chosen in part “to suggest the swiftness with which the women graduates of the University, in the few years since full Academic status was accorded them, have won a place for themselves in every branch of the national life, both here and overseas” (v-vi). The editorial committee notes that given how the women of the university have “greatly multiplied its links with the Continent,” it shouldn’t be surprising that “a prominent feature of the pages which follow should be a group of stories and sketches in the chief European languages, contributed or chosen to illustrate woman’s art in the short story of to-day” (vi, vii). The short stories that make up this “prominent feature” are explicitly labelled as such in the table of contents, and Mansfield’s contribution is not one of them (vii). However, I think the choice to highlight “woman’s art in the short story of to-day” globally in this collection as a whole reveals that Mansfield, who used “the short story as her sole narrative art form,” was likely also included because the editors considered her an important contributor to the development of the short story, especially ones that focus on women (Atalanta’s Garland vii; Kimber 4).

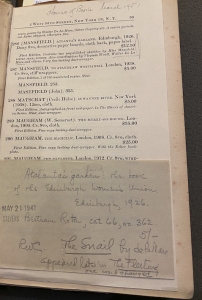

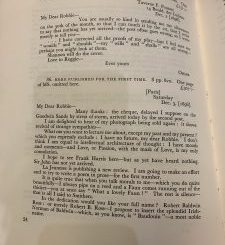

Another reason to consider Mansfield’s inclusion in terms of her legacy could be because the two new works of hers that are included are brief and incomplete, and so it seems less likely that their inclusion was chosen due to their ability to fully explore themes relevant to this collection. Many of the works in Atalanta’s Garland appear to be published here for the first time—a slip included in the front cover of the book notes that the book contains the poem “The Snail” by Walter de la Mare, which was later published with one word changed in de la Mare’s The Fleeting. Some writers contributed pieces that appear to have been written specifically for this collection, such as Cecile Walton’s “Atalanta in Caledonia: Notes on Women’s Contribution to the Arts in Scotland,” which seems especially likely as Walton had served as an advisor to the editorial committee (Atalanta’s Garland vii). And though Virginia Woolf’s contribution, “A Woman’s College from Outside,” is a vignette originally written into then deleted from the draft of her novel Jacob’s Room, the piece, which explores the dynamics of a group of female university students and a narrating character’s burgeoning attraction to another woman, feels very deliberately chosen for this collection (Bishop 116). The two unpublished sketches of Mansfield’s appear as the second literary inclusion in the collection, contributed by her executor John Middleton Murry after her death. Since her work was included posthumously, Mansfield would not have been able to write or clean up something for this book specifically. In some ways, Mansfield’s inclusion could be less about her ability to contribute a new piece geared towards the themes of this collection and be more about how she was viewed as an important contributor to the development of the short story as a woman by the young women who curated this collection.

The two sketches of Mansfield’s included are titled “Little Jean” and “Lucien.” “Little Jean” depicts a one-and-a-half-year-old boy named Jean, and “Lucien” describes a nine-year-old boy Lucien, the son of a dressmaker. What we have of “Little Jean” is a little under four pages and flits from a brief description of Jean—from “the tassel of [his] cap, which was much too big for him and hung down over one eye with a drunken effect” to his “merry, almost cunning little eyes”—and carries on to the beginning of a walk Jean takes with his mother in the Jardins Publiques (Mansfield 2, 3). The less than two pages of “Lucien” describe the boy (“his hair was fine, like down rather than real hair”) and his errand-running (“trott[ing] along like a little cat out-of-doors”) for his mother (Mansfield 6). Neither sketch gets far enough along to introduce substantive plot, instead they paint vivid pictures of character through small details and by relaying these characters’ thoughts and interactions with the people and world around them mediated by the narrative voice. Mansfield is often presented at the start of a movement, a “‘slice-of-live’ Chekhovian tradition,” in literary modernism that rejects “conventional plot structure and dramatic action in favour of the presentation of character through narrative voice,” and often as “one of its most exciting and cutting-edge protagonists” (Kimber 6).

In reading the two sketches alongside “The Garden Party,” it seems that all three demonstrate a similar ability to convey quiet observations, many that are very aware of things like socioeconomic class, through the point of view of a primary character who is less explicitly aware of these dynamics. All three stories show an easy shifting between interior thought and exterior action in an application of free indirect discourse that feels stylistically distinct from, though in conversation with, the kinds of stream of consciousness found in Woolf’s short stories and in Arthur Schnitzler’s “Fräulein Else.” In looking at Atalanta’s Garland alongside “The Garden Party,” I think the sketches of Mansfield’s further demonstrate some of the stylistic elements of her writing that perhaps carry through multiple pieces of her work, such as her ability to capture slices of life as a way of refracting greater insights, her ability to “depict with acute psychological insight the workings of [her characters’] minds” while developing for each “a distinctive voice,” and her “intimate method of storytelling” due to her use of free indirect discourse (Kimber 11, 16). I think her inclusion as a non-Scottish writer who did not attend the University of Edinburgh and was not in a position to contribute something new specifically for this collection suggests that young female writers at the time viewed her as a preeminent figure in the development of women’s art and the short story, and these sketches can help illustrate some of her stylistic trademarks.

References

Bishop, E. L. “The Shaping of Jacob’s Room: Woolf’s Manuscript Revisions.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 32, no. 1, 1986, pp. 115-135. http://www.jstor.com/stable/441309.

Edinburgh University Women’s Union, editors. Atalanta’s Garland. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 1926.

Kimber, Gerri. Katherine Mansfield and the Art of the Short Story. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Mansfield, Katherine. “Two Unpublished Sketches.” Atalanta’s Garland, edited by the Edinburgh University Women’s Union, Edinburgh University Press, 1926, pp. 2-7.

Recent Comments