What a Translation Cannot Convey: Mortality and Artistry in Sartre’s “Le mur” by Katie T.

Inside cover of the 1965 edition of Sartre’s “Le mur”

I compared the French text of the 1965 edition of Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Le mur” [“The Wall”] with Lloyd Alexander’s English translation. The story follows three men who are sentenced to death for their alleged anarchist beliefs and actions during the Spanish Civil War, and it specifically focuses on the night before their execution. While waiting in a cell together, the men, particularly the narrator, Pablo, describe the ways in which their bodies and minds react to their imminent death and to the idea of their own mortality. Unique to this edition of “Le mur” is Walter Spitzer’s lithograph (shown below). Through its cool and neutral colors and dark tones, the image conveys the men’s physical (perspiring and turning grey) and emotional (feeling uncertain, fearful, and agonized) responses to death. Its indistinct lines and haphazard, overlapping blotches of ink further emphasize the prisoners’ gradual degradation and symbolize their fleeting presence on Earth. As for comparing the French and English versions of the text, even though the latter corresponds closely to the original’s language and style, a number of subtle translational differences exist. In particular, in order to help readers better understand the original text’s commentaries on the theme of mortality, I wanted to draw attention to specific aspects of the French version that the English translation either misrepresents or does not fully embody the meaning of. Additionally, since writing is an art of word choice and word play, I wanted to highlight some examples from the original version that demonstrate Sartre’s artistry, which the English translation is unable to illustrate.

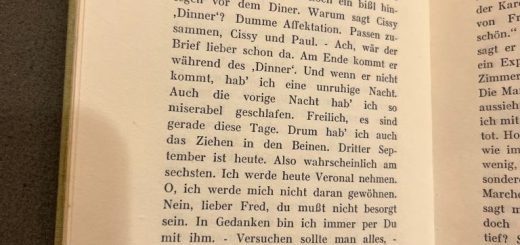

Lithograph by Walter Spitzer included in the 1965 edition

To start, one aspect that the original text emphasizes more than its English counterpart is the transformation, both physical and mental, of the men after they realize they are going to die. For instance, when the narrator describes his body, he states, “J’étais obligé de le toucher & de le regarder pour savoir ce qu’il devenait, comme si ç’avait été le corps d’un autre” (29) / “I had to touch it and look at it to find out what was happening, as if it were the body of someone else” (12). While the English clause “what was happening” does convey the sense that the narrator’s body experiences something abnormal, the French “ce qu’il devenait” [what it was becoming] uses the verb “devenir” [to become] to emphasize the distinct transformation of the body: the physical changes of a person who knows he is going to die are so great that his body gradually becomes an unrecognizable new form. The same verb, “devenir,” is subsequently used to describe the transformation of the cellar. Mirroring the narrator and his companions, “[l]a cave était devenue toute grise” (30) / “The cellar was all grey” (13). In this instance, by using the linking verb “was” instead of the direct translation of the French verbs “était devenue” [had become], the English version places emphasis on the physical description—“all grey”—of the cellar rather than its process of becoming all grey. This transformation of the cellar, however, is significant; it not only mimics the physical degradation of Pablo and the other prisoners who have started to turn grey, or die, in anticipation of their executions but also represents Pablo’s changing (decaying) view of the world around him in response to his imminent death, for he is the one who perceives the cellar’s discoloration. The original French text further invokes this idea of transformation with its repeated use of the construction “ne…plus” [no longer/not anymore], which the English version rarely translates. For instance, Pablo employs the “ne…plus” construction in directly voicing the effects of his perceived mortality on his thoughts when he observes, “Et, depuis que j’allais mourir, plus rien ne me semblait naturel” (25) / “And since I was going to die, nothing seemed natural to me [anymore]” (9). He uses it again when he talks about his and his comrades’ bodies—“Nous autres nous ne sentions plus guère nos corps” (26) / “The rest of us hardly felt ours [anymore]” (10)—as well as when he thinks back to all that used to be important in his life—“je me foutais de l’Espagne & de l’anarchie : rien n’avait plus d’importance” (35) / “I thought to hell with Spain and anarchy; nothing was important [anymore]” (16). Ultimately, the physical and mental transformation the men undergo after realizing their mortality—the transformation that the French text stresses—supports the existentialist principle of life, or existence, above all else; when this most important value is threatened to be taken away, both the body and mind destabilize and no longer resemble their natural, normal states.

In addition to emphasizing the transformation from life to death, the original French text has the ability to prevent misinterpretations that could result from reading only the English translation. For instance, after Pablo concludes, “I didn’t want to think any more about what would happen at dawn, at death,” he explains why: “It made no sense” (10). While the French expression the narrator employs—“Ça ne rimait à rien” (26)—can be translated to “it was senseless,” the word “senseless” in this case means “pointless.” Pablo dislikes thinking about his impending death, not necessarily because he cannot understand it—that “it [makes] no sense,” as the English translation implies—but because doing so is senseless; it will neither change his fate nor quell his uneasiness. Additionally, the English translation frequently uses the word “hell” as a means of emphasis, as in the phrases, “What the hell are they doing?” and “cold as hell” (13). However, the French phrases from which these translations are derived—“Qu’est-ce qu’ils viennent foutre?” and “[m]ince de froid” (30)—invoke strong language or words of emphasis but not specifically the word “hell.” Because this story deals with the themes of punishment, death, and mortality, this distinction is significant, as some readers might be temped to overanalyze the word “hell,” despite Sartre’s existentialist, and by association, atheist, beliefs.

Lastly, I wanted to present examples of Sartre’s craftsmanship that readers unable to understand written French would otherwise miss out on. Specifically, as the story pertains to life, death, and the transition from the former to the latter, Sartre cleverly employs diction to evoke these themes, even when describing objects and actions that have presumably little to do with them. The word “soupiraux” (17), for example, denotes the windows in the cellar, but within the term is the word “soupir,” which is used to mean “last breath” or “dying breath” in the expression “dernier soupir.” Sartre similarly employs the word for breathe, “souffler,” when one of the prisoners, Tom, returns from the bathroom and the narrator remarks, “Il…ne souffla plus mot” (25), literally “[h]e no longer breathed a word,” as well as when one of the guards, Pedro, “vint souffler la lampe” (30), or “came to blow out the light” (13). Additionally, when the narrator observes that “Tom avait enfoui sa tête dans ses mains” (21) / “Tom had hidden his face in his hands” (6), he uses the verb “enfouir,” which means “to bury.” Furthermore, the expression with which Pablo describes the man who interrogates him, “d’un air à me faire rentrer sous terre” (31) / “with a look that should have pushed me into the earth” (14), could also be understood as “with a look that has the ability to make me go underground.” Both examples relate to the idea of being buried post-mortem.

Another example of Sartre’s clever diction comes from Tom’s description of an execution practice that he had previously heard about: “Tu crois qu’ils achèveraient les types? Je t’en fous. Ils les laissent gueuler. Des fois pendant une heure. Le Marocain disait que, la première fois, il a manqué dégueuler” (17) / “You think they finish off the guys? Hell no. They let them scream. Sometimes for an hour. The Moroccan said he damned near puked the first time” (2-3). In a way that the English version cannot, the French text links the victim and executioner with similar verbs, “gueuler” and “dégueuler.” In doing so, the text makes reference to a point on which Pablo later reflects: “Ces deux types[,]…c’étaient tout de même des hommes qui allaient mourir. Un peu plus tard que moi, mais pas beaucoup plus” (31-32), the point that everyone, including the officers who interrogate and sentence him, is ultimately subject to the same fate (death), that mortality is inevitable. In stemming from the word for mouth, “gueule,” both verbs also connect to the lengthy descriptions of the human body and its reactions to suffering and death within the anecdote and throughout the story itself.

Finally, right after the narrator remarks that he and Tom are “pareils & pires que des miroirs l’un pour l’autre” (23) / “alike and worse than mirrors of each other” (7), Tom asks, “Tu comprends, toi?,” to which Pablo responds, “Moi, je comprends pas.” Although this mirroring of dialogue is present in the English translation, the stress pronouns “toi” and “moi,” which are commonly used in French but not in the same way in English, render the mirroring effect even stronger in the original version. This mirroring also occurs visually, as seen in the attached image.

Readers can see Sartre’s artistry in the way that Tom’s question and Pablo’s response mirror each other both verbally and visually.

Ultimately, I hope readers, especially those unable to comprehend written French, find my analysis helpful for thinking about one of the text’s most prominent themes, mortality. As a lover of literature, I was excited to witness Sartre’s artistry, so I also hope that this post helps readers to appreciate Sartre’s skillful creativity, which renders his work not only philosophically compelling but also beautiful to read.

Acknowledgements: Two online French-to-English dictionaries, WordReference and Linguee, were instrumental in my comprehension of certain words’ and phrases’ definitions and usages. Other words and phrases I was able to translate from my knowledge of the French language.

Fantastic! Thank you. A beautiful introduction, I’m excited to read the english and hopefully french version too.