Oscar Wilde: A Children’s Picture Book Writer? by Simon G.

Cover Page of The Happy Prince and Other Tales

Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince And Other Tales is a collection of children’s stories first published in 1888. It contains the stories “The Happy Prince,” “The Nightingale and the Rose,” “The Selfish Giant,” “The Devoted Friend,” and “The Remarkable Rocket.” The digitized manuscript of this collection available through the Rubinstein Library is not the original edition, but rather a 1913 republication. However, this younger edition arguably has more historical, cultural, and aesthetic significance than the original – primarily because of the striking illustrations by Charles Robinson.

Robinson was a prominent British illustrator of children’s stories in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Among his other achievements are illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Grimms’ Fairy Tales.

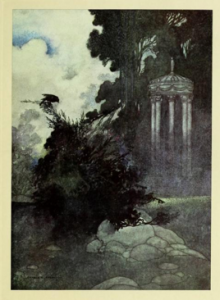

Indeed, scanning the pages of the Wilde stories collection, I could not help being reminded of reading Carroll, Brothers Grimm, Anderson, and even C.S. Lewis when I was younger. I cannot say if I happened upon editions with Robinson’s illustrations, but there is certainly a persistent tradition when it comes to illustrating children’s literature. For instance, it is worth comparing one of Robinson’s illustrations for “The Devoted Friend” and the drawing of the iconic lamppost scene from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by the talented Pauline Baynes (who did all the Chronicles of Narnia illustrations). Both drawings depict an idyllic natural landscape with just the right touch of human civilization in the midground.

One may say I am grasping at straws, but these illustrations are of course informed by the story’s subject, and there is undoubtedly a set of common themes and motifs that pervades children’s literature. Much of it is rooted deeply in the foundations of western canon like the Bible and the Classics. The drawing on the left is Robinson’s interpretation of the protagonist Hans’ garden in “The Devoted Friend,” which is considered the most beautiful garden in the countryside. The drawing on the right is one of the reader’s first glimpses of the fictional land of Narnia where the protagonists cannot return once they grow too old. Both evoke the imagery of the Garden of Eden. “The Selfish Giant” likewise features a garden from which the Giant expels a group of children that play there (and to really scream Bible in the reader’s face, Wilde throws in a not-so-subtle allusion to Jesus at the end). The catalyst for the nightingale’s actions in “The Nightingale and the Rose” is the student lamenting the absence of roses in his garden.

The garden archetype’s prevalence is unsurprising: Eden is a symbol of innocence and purity, and thus the imagery of it is greatly associated with children. Children are unhardened by reality, so to speak, and their free imaginations are easily captivated by and sucked into these many fictional Utopias. As such, the illustrations serve as invaluable assistants to the text in imprinting on children’s psyches the exciting, mysterious, and fantastical fictional worlds, and in doing so revealing the shared biblical roots of these diverse stories.

But it would be impertinent to completely dismiss Wilde, Lewis, and Carrol as mere variations on one another. Wilde’s stories are so full of ironizing the ideal and loss of innocence that one is left to wonder if it is right to classify his works as children’s literature at all. Charles Robinson’s drawings certainly seem to suggest they should. But in fact, Hans in “The Devoted Friend” dies in the end because he is too devoted to a friend who does not reciprocate his loyalty. The nightingale in “The Nightingale and the Rose” sacrifices herself for a young lover to win over a girl only for him to find the girl is not interested in him. The swallow in “The Happy Prince” similarly sacrifices himself to helping the poor, though no one knows of his deeds. Suddenly these wonderous worlds suggested by the illustrations may not seem so captivating. It is not predetermined that these stories must come with illustrations; another early edition of a Wilde short story collection, The Happy Prince and Other Fairy Stories, is also available at the Rubinstein, and it does not contain such illustrations.

So is Wilde playing with the reader, luring him into a tragedy with the promise of an innocent tale? Is it an error of judgment on the part of the publisher and illustrator to market Wilde’s stories to children?

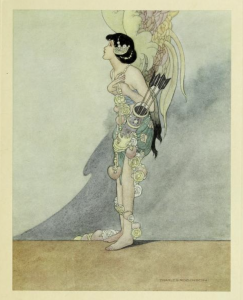

In attempting to resolve the discrepancy, I found myself remembering another genre of literature that I had read when I was younger that had memorable illustrations with similar archetypal imagery: fables. As with the case of the biblical association, Robinson’s illustrations really drive home how close Wilde’s stories follow a traditional fable narrative. The image on the left below is Robinson’s interpretation of the nightingale in “The Nightingale and the Rose,” who frankly looks more like Tinkerbell than a bird (perhaps rightly so). On the right is an illustration of Aesop’s fable The Ant and the Grasshopper by Milo Winter, an American illustrator. In both drawings, the personification of the characters betrays their character traits, traits that soon become their fatal flaws. The nightingale is depicted as a romantic guardian angel figure, and she indeed dies because of her desire to be a guardian angel. The grasshopper is drawn as a lackadaisical Bohemian who condescends to the hardworking ants – he starves come winter.

The personification in the images parallels the personification of these animals in the actual text, and it is their human faults that define the story. Just as with fables, the errors committed by characters in Wilde’s stories teach readers simple yet powerful lessons. In the case of “The Nightingale and the Rose,” one such lesson might be “Altruism is not universally good.” The nightingale vainly sacrifices herself to create a red rose that a student gifts to a girl he desires, only for her to repudiate his gift and favor another student of higher social standing. One must be careful so as not to succumb to false idealism in the way the nightingale gives her life for love — love that turns out to be unrequited.

It seems that Wilde’s stories are structured largely to convey such life lessons, which are equally relatable, significant, and necessary for children and adults. I cannot imagine separating the fable genre into “adult fables” and “children’s fables.” These stories are structured to deliver a moral message, and it is not as if different morals apply to different ages. Yes, we recognize that children, by virtue of their inexperience, are more fallible, and so we tend to be more forgiving for their transgressions, but that does not make a self-aware child’s actions any less right or wrong. In fact, that is all the more reason to engage children with fables: fables teach what children have not lived long enough to learn from experience. Robinson’s illustrations play a crucial role in revealing the fable’s lesson and appealing to a younger audience. They increase the age range that the stories are marketed for, they do not constrain it. Adults should not feel alienated by their presence (just as children should not be alienated by the stories’ unhappy endings). The universal truths contained in these stories are valuable to all, and illustrations simply help children extract them from the text.

Links to Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Robinson_(illustrator)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milo_Winter

https://archive.org/details/happyprinceother1888wild/mode/2up

Recent Comments