Camus: Art in the Service of Truth and Freedom for the Masses by Michael P. and Nick K.

Camus’s 1957 acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize ultimately consists of an expression of gratitude for an award he feels somewhat unworthy of receiving, and an elaboration upon what he views his role as an artist is in life in the midst of what he calls “more than twenty years of absolutely insane history.” In the speech, Camus makes clear that he views the artist and writer as someone who speaks for the experience of the masses. He is not above them, but rather with them, saying that he never places his art above anyone, because “it excludes no one and allows me to live, just as I am, on a footing with all.” His goal, as he sees it, is to “unite the greatest possible number of men,” and to act in “the service of truth and the service of freedom.”

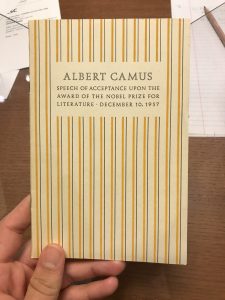

The primary message that Camus wishes to send is complemented to a degree by the format in which the speech was printed. It appears in a small, simple pamphlet without many extravagant design choices or artistic liberties taken. Those who printed and distributed the speech in this manner stayed true to Camus’s desire to produce works and send a message that would be accessible to and representative of all. With that being said, reading the speech as written down, translated, and not spoken aloud by Camus himself, there is undoubtedly a degree of emphasis and clarity lost that would have been present in the original speech as read by Camus. In spite of this, the message of this relatively short and direct speech remains apparent in reading the text as it exists within the pamphlet.

Camus also goes on to state the impact history makes on the life of an author. We see him mention how a writer “cannot put himself today in the service of those who make history; he is at the service of those who suffer it”. This is then followed up with one of the most powerful quotes as he describes “These men, who were born at the beginning of the First World War, who were twenty when Hitler came to power…, who were then confronted as a completion of their education with the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War…- these men must today rear their sons and create their works in a world threatened by nuclear destruction. Nobody, I think, can ask them to be optimists.” In the Adulterous Woman, we see the essence of this pessimistic mindset that Camus alludes to take hold of Janine through much of the story, where she expresses a general sense of disappointment with the state of her life surroundings relative to her expectation. This is exemplified by the way she thinks of the trip, of which she “had dreamed too of palm trees and soft sand. Now she saw that the desert was not that at all, but merely stone, stone everywhere…”. However, she does have a realization, an understanding that freedom was within her grasp and that “She wanted to be liberated even if Marcel, even if the others, never were!”. Camus describes a similar sentiment in his speech as “each generation doubtless feels called upon to reform the world”. The way that Camus sees it, society continues to have hope as does Janine who finds it while standing upon that hill.

Given the fact that the speech was written and delivered in 1957, it isn’t surprising that it connects to “The Adulterous Woman” and bears this and other apparent thematic similarities. Camus in his Nobel speech talks about a desire to lead people to truth and freedom. In the story, Janine finds herself in a life which is utterly without meaning and passion. She catches glimpses of freedom and excitement throughout the course of the story, whether in the fort gazing over the vast horizon or during her covert escapade into the night, yet it remains elusive. Camus in this story seems to be doing some of his characteristic contemplation about finding meaning in a life seemingly devoid of it, using a social dynamic and situation that would be familiar to his readers and would perhaps reach the masses as he hopes to. The story is also interestingly written in a way that is very sympathetic and understanding of Janine, closely following her thoughts and perspective on the different events that occur. While no true act of adultery is committed, Camus makes an obvious effort to understand what exactly she’s going through while passing minimal judgment, something which is also emphasized in his speech where he states that “…true artists scorn nothing. They force themselves to understand instead of judging”, and similarly asks of his listeners “…what writer would dare, with a clear conscience, to become a preacher of virtue?”. It is clear that Camus is trying to communicate a story about truth and freedom in a life without it, describing the events of the story in a way that is coherent with his desire not to exclude or really convince anyone of right or wrongdoing.

Recent Comments