Audio Collection: Tell My Horse

Beyond the American South, Zora was fascinated by the Caribbean — many of the southern black folk songs she would go on to record in Jacksonville featured elements of Bahamian culture. The Bahamas, Jamaica, and Haiti were all of great interest to Zora as spaces of “primitive” practice such as voodoo, as they had been less “drained by formal education,” and were in some ways a step closer to African source of voodoo practice.

In 1935, she returned to Columbia to complete a doctorate in anthropology, with voodoo as her major area of interest. A year later, the Guggenheim Foundation awarded Hurston her first grant to conduct research in the Caribbean. She traveled to Jamaica for a year, and then spent six months in Haiti until she ran out of funding. Later in 1937, the Foundation renewed her grant, lending her the opportunity to spend an additional three months in Haiti. This study period ended due to a serious, yet mysterious illness, which she believed was related to her voodoo studies and ultimately she left the island. She returned to the United States in September of 1937, and by the following October, her part-anthropological, part-biographical work on Jamaica, Haiti, and voodoo, Tell My Horse, was published.

Sound was a central focus of Tell My Horse, particularly when Hurston documents the proceedings around Voodoo ritual. Her approach to this study was not executed in the standard language of research of the time. The text itself neither aligns fully with serious or traditional anthropology or fiction. According to a critical text written by Wendy Dutton called The Problem of Invisibility, ‘Apparently, Hurston toyed with the idea of writing two different voodoo books, one for the anthropological world and one “‘for the way I want to write it,”’ (). The field of black sound studies had not yet been institutionalized, so critical evaluation of her anthropological voice is difficult.

How is Sound portrayed in the text?

- Page 163: Chanting (No tune or rhythmic aid)

- Page 170: Chanting, this time monotonous

- Page 173: The drums and cracking bones

- Page 184: The lost tune of the most beautiful song

Imagine what Zora could capture if she had been able to record the actual sounds, chants, songs, and drums as she was able to do with federal funding in Florida. It is interesting to consider the aspects of reality that are lost when a three-dimensional, multi-sensory experience is portrayed through text alone .

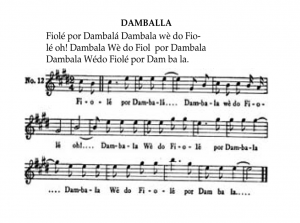

Some songs were preserved and presented in the form of musical notation at the end of Tell My Horse, in a section titled Songs of Worship to Voodoo Gods. The sheet music for two songs are included below, as well as recordings of the songs played on the piano. It is unlikely that the piano would have been an instrument present during a Haitian voodoo ceremony. However, these piano recordings allow listeners hear to a bare-bones version of the aural experience Hurston attempted to visually represent. In this way, listeners listeners can begin to comprehend what is lost when the sonic can only be dictated over text.

“Maitresse Ersulie”

“Janvalo”

“Janvalo”

Some songs featured in Songs of Worship to Voodoo Gods, like “Damballa” and “Petro”, can actually be found on the album, “Haitian Vodou – Ritual music from the First Black Republic 1937-1962” released in 2016 (Tracks 1 and 12, respectively). Although these tracks are not exact duplicates, they do bear lyrical and, in some cases, rhythmic resemblance. Further, the years in which these songs were recorded (1937-1962) do intersect with Hurston’s time researching and writing in Haiti. Listening to these recordings, one can begin to imagine and appreciate the sonic complexity of Haitian Voodoo ritual music that may not be apparent through written notation alone.

“Damballa”

“Petro”