By Amy Weng

Introduction

London was not only indisputably the center of the early English book trade, but also the hub for noteworthy Church of England preachers to deliver sermons to the local populace, Parliament, and court on theological, political, and moral issues, ranging from the regulation of personal conduct to vehement attacks on Catholicism. Beyond Sundays, events like festivals, feasts, fast days, weddings, and funerals also became regular occasions for the performance of sermons (Green). In a highly religious society, attending sermons formed an essential part of ordinary life, and great multitudes flocked to the pulpits of the most popular preachers (Craig).

With the emergence of print, sermons became increasingly accessible to the public beyond their initial oral performances, enabling preservation as well as distortion. The proliferation of unauthorized prints of sermons, which oftentimes included deviations from the original, incentivized preachers to revise and prepare their sermon notes into prose and sometimes even expand them into full treatises despite an initial reluctance to endorse the written text to be just as spiritually powerful as the spoken word (Rigney). Delivered, published, printed, and sold primarily in London, sermons form an indispensable literary resource for investigating ethical attitudes in a rapidly growing urban setting.

Due to an influx of both domestic and continental European migrants, London’s population more than doubled and became the largest in Europe by the end of the 17th century (Lincoln 7). The explosive population growth also meant growing issues of poverty, unemployment, and debt, with prisons primarily holding debtors, not violent criminals (Lincoln 13). The city’s underworld consisted of vagrants and criminals, and one of the measures to prevent them from contributing to social unrest or trouble was to ship them off to England’s newly established colonies or wars abroad (Lincoln 12). Moreover, beggary and vagrancy–“masterless men” wandering around without any means of income except through begging–were severely criminalized since 1572 (“Vagabond Act”).

In 1601, Parliament passed a law demanding that parishes provide different structures of relief via taxes to specific demographics of the poor: that those who were able to work but willfully idle need to be put into work, the “lame, impotent, old, blind, and such other” would receive monetary and material aid such as housing within almshouses, and orphan children be given apprenticeships to allow them to learn to be productive members of society (“1601: 43 Elizabeth 1 c.2”). In other words, the government assigned local ecclesiastical authorities the fiscal responsibility of addressing different types of poverty in their communities.

Sermons and Charity

Given the longstanding Christian emphasis on the virtue of charity, which includes both love for God and other humans as well as God’s love for humans, we investigate how the prominent preachers characterized charitable giving and poor relief, as well as the depiction of the less fortunate, in their sermons. We separately examine their approximate preaching locations, textual contents, and marginal annotations.

Our corpus, hereafter referred to as the charity sermons dataset, consists of 70 texts by six prominent early modern English preachers. All of these texts but one were published in London, with the only exception being Hall’s A modest offer (1644) which was published at Oxford. The only two texts that were not strictly derived from sermons are Hall’s A modest offer and An humble remonstrance (1641), but we included them because they both have clear intended audiences: the Westminster Assembly and Parliament respectively. Indeed, what differentiates the texts in the charity sermons corpus from the other publications by these preachers is that they were addressed to particular audiences, whether it be mourners at a funeral service or the king. The six preachers are introduced briefly below with information from their corresponding biographies in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, as well as the preaching locations and audiences of their sermons.

-

-

- William Crashaw (c. 1572-1625): Preacher at the Temple in London who favored puritanism, especially the work of the puritan William Perkins. He supported English colonialism in North America and spoke vehemently against Catholicism. (Kelliher)

-

- Therefore, it is unsurprising that in our corpus, there is a sermon by him that was preached to the leaders of the Virginia Company. His other two sermons in the dataset turn out to be duplicates, for they are all prints of his anti-Catholic sermon preached at St. Paul’s Cross in 1607.

-

- Thomas Gataker (1574-1654): Preacher at Rotherhithe, London who published over two dozen sermons and treatises in the 1620’s and another two dozen after 1637. He favored episcopacy and presbyterianism and was well-acquainted with many lawyers and merchants, such as the first governor of the English East India Company. (Usher)

-

- The six London funeral sermons in our corpus are all by him, dedicated to London merchants, his own relations, another pastor, and the wife of a pastor. Moreover, he delivered two out of the three wedding sermons in the dataset, as well as one sermon at a school founded by one of London’s livery companies. There are five sermons preached locally by him in Rotherhithe, one of which commemorates England’s victory over the Spanish Armada, and two sermons which he preached at Sergeant’s Inn, one of London’s four Inns of Court that function as associations and educational institutions for lawyers.

-

- William Gouge (1574-1653): Preacher at St. Ann Blackfriars, London who upheld Calvinism and attracted large audiences to his sermons for decades. He supported the monarchy despite his association with parliamentary presbyterians at the beginning of the civil war, and he was accused of overly encouraging puritanism by William Laud, then bishop of London. (Usher)

-

- In our corpus, there is one sermon by him addressed to the Artillery Company of London, two preached locally at Blackfriars, one before the House of Commons, two before the House of Lords, and two other sermons that are harder to categorize. For the last two, I have labeled them both as “historical” because one is a memorial of Queen Elizabeth and the other is the history of a penitent’s return into the church.

-

- Joseph Hall (1574-1656): Bishop of Norwich and former bishop of Exeter with over forty printed sermons. He publicly defended the episcopacy and was imprisoned for a time for treason when trying to preserve the interests of bishops in the face of parliamentary opposition. (McCabe)

-

- In this corpus, there are seven sermons by him that were preached before the king, two before the House of Lords, one at the notable psychiatric hospital of St. Mary Bethlehem, two at St. Paul’s Cross, and one at Gray’s Inn, which is one of London’s Inns of Court. Moreover, there are the two aforementioned non-sermons.

-

- John Preston (1587-1628): Preacher at Lincoln’s Inn, London and Holy Trinity Church, Cambridge, as well as master at Emmanuel College of the University of Cambridge. He was widely influential for his sermons though often accused of nonconformism. A Calvinist puritan, he preached against Arminianism before the king and criticized aspects of the established church. (Moore)

-

- Of his 20 sermons in the corpus, four were preached before the king, six at Lincoln’s Inn, which is one of London’s Inns of Court, and one at Holy Trinity Church. It is uncertain whether his remaining nine sermons in the set were preached at Lincoln’s Inn or in Cambridge.

-

- William Whately (1583-1639): Preacher at Banbury who favored and actively encouraged puritanism. He preached strongly in favor of Calvinist predestination and sparked controversy with his tracts on conditionally allowing divorce and corporal punishment in marriage. (Eales)

-

- He delivered one wedding sermon found in this corpus, and his seven sermons were sermons preached to normal churchgoers in Banbury.

-

- William Crashaw (c. 1572-1625): Preacher at the Temple in London who favored puritanism, especially the work of the puritan William Perkins. He supported English colonialism in North America and spoke vehemently against Catholicism. (Kelliher)

-

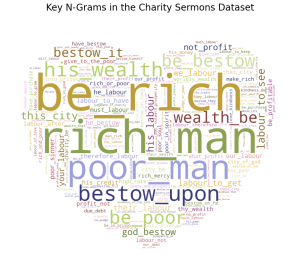

In summary, we have defined these preachers’ sermons into categories roughly by audience. These categories are funeral, company, hospital, school, wedding, local, Inns of Court, Inns of Court/ local, monarch, parliament (House of Lords and House of Commons), historical, and Westminster Assembly. The “local” category is a catch-all for those that do not dwell on particular historical or contemporary topics or cater to a specific type of audience. The “Inns of Court/ local” contains Preston’s sermons that we cannot ascertain a specific preaching location for. To explore these texts, we further defined a set of keywords of interest. These include terms related to charity, socioeconomic status, credit, debt, labor, money, commodities, hospitals, orphanages, city and citizenship, and vagrancy. The full list can be found in this file: bigrams.ipynb. Examining sequences of words in the texts extracted from their lemmatized EarlyPrint Lab XML file versions (see this page for an overview for our sources of data), we find that the most frequent bigram and trigram phrases involving our keywords are ones that involve forms of “be” and pronouns, with the language of states of wealth and poverty dominating over the other terms of interest. However, the problem with simply looking for phrases is that much of this language is theological and figurative, with poverty and wealth meaning spiritual rather than material conditions in many instances.

When looking within the categories of sermons we have defined, we find a distribution of phrases that is generally consistent with the language we expect to find in a sermon of that type, such as mentions of wife in the keywords phrases of wedding sermons. We find “wealthy_wife,” “wife_without_wealth,” and “wife_for_wealth” in one of Gataker’s wedding sermons, with the importance of wealth being rejected in favor of better virtues:

- “yea men are wont to seeke wiues for wealth. But saith Salomon, as[e] a good name, so a good wife, a wise and a discreet woman is better then wealth; her price is far aboue pearles”

- “Neither saith he, a wealthy wife is the gift of God: And yet is[r] wealth also Gods blessing, where it is accompanied with well-doing. But, a discreet, or a wise woman is the gift of God.”

- “so better it is to haue a wife without wealth, then to haue wealth without a wife.”

Whereas these sentences around the keyword of “wealth” do not specifically address material giving, the statement that wealth is a blessing only when it is supported “with well-doing” is nonetheless suggestive of a moral imperative to be generous with that wealth to help others. The following are the ten most common short phrases with keywords in the different categories.

-

-

- wedding: [(‘have_wealth’, 4), (‘worldly_wealth’, 3), (‘man_without_money’, 3), (‘god_bestow’, 3), (‘have_bestow’, 3), (‘their_profit’, 3), (‘strong_city’, 2), (‘possession_wealth’, 2), (‘wife_for_wealth’, 2), (‘man_rich’, 2)]

- company: [(‘present_profit’, 6), (‘his_money’, 2), (‘fence_city’, 2), (‘labour_the_conversion’, 2), (‘poor_man’, 2), (‘poor_may’, 2), (‘their_profit’, 2), (‘must_labour’, 2), (‘how_poor’, 2), (‘profit_and_pleasure’, 2)]

- funeral: [(‘fifty_pound’, 4), (‘her_charity’, 3), (‘rich_man’, 2), (‘bequeath_it’, 2), (‘charity_as’, 2), (‘such_poor’, 2), (‘relief_of_the_poor’, 2), (‘have_labour’, 2), (‘lend_we’, 2), (‘wealth_of_this’, 2)]

- Inns of Court/local: [(‘be_rich’, 24), (‘rich_man’, 16), (‘therefore_labour’, 9), (‘your_labour’, 9), (‘his_wealth’, 9), (‘bestow_upon’, 8), (‘thy_wealth’, 8), (‘labour_to_see’, 8), (‘his_credit’, 8), (‘labour_to_have’, 7)]

- local: [(‘rich_man’, 67), (‘be_rich’, 45), (‘poor_man’, 44), (‘bestow_upon’, 26), (‘this_city’, 22), (‘his_wealth’, 21), (‘be_bestow’, 20), (‘poor_sinner’, 19), (‘labour_after’, 19), (‘their_labour’, 19)]

- parliament: [(‘he_bestow’, 2), (‘city_of_refuge’, 2), (‘how_rich’, 2), (‘justice_charity’, 2), (‘we_labour’, 2), (‘say_city’, 1), (‘city_and_carry’, 1), (‘be_bestow’, 1), (‘style_the_city’, 1), (‘poor_blind’, 1)]

- historical: [(‘city_of_our’, 3), (‘city_of_god’, 3), (‘this_city’, 2), (‘city_of_the_lord’, 2), (‘lay_in_prison’, 1), (‘prosperity_but’, 1), (‘hard_labour’, 1), (‘faithful_city’, 1), (‘mass_of_money’, 1), (‘industry_of_man’, 1)]

- hospital: [(‘be_rich’, 16), (‘rich_man’, 9), (‘wealth_be’, 7), (‘charge_the_rich’, 5), (‘our_wealth’, 4), (‘their_wealth’, 3), (‘your_wealth’, 3), (‘rich_merchant’, 3), (‘rich_that’, 3), (‘we_rich’, 2)]

- school: [(‘labour_not’, 2), (‘your_labour’, 2), (‘be_profitable’, 1), (‘precious_and_profitable’, 1), (‘alphius_the_usurer’, 1), (‘good_debtor’, 1), (‘one_city’, 1), (‘consist_of_city’, 1), (‘pension_to_the_poor’, 1), (‘his_bounty’, 1)]

- Inns of Court: [(‘be_rich’, 39), (‘labour_to_see’, 18), (‘be_poor’, 17), (‘rich_man’, 17), (‘poor_man’, 12), (‘his_wealth’, 12), (‘bestow_it’, 10), (‘he_bestow’, 9), (‘labour_to_get’, 9), (‘be_bestow’, 8)]

- westminster assembly: [(‘town_or_city’, 1), (‘some_city’, 1), (‘my_poor’, 1), (‘this_poor’, 1)]

- monarch: [(‘true_coin’, 3), (‘his_poor’, 3), (‘honour_wealth’, 3), (‘his_credit’, 3), (‘commodity_be’, 2), (‘high_rate’, 2), (‘labour_for_truth’, 2), (‘some_rich’, 2), (‘rich_and_full’, 2), (‘labour_to_have’, 2)]

-

Funeral sermons are indeed the most direct with their discourse of charity, as Gataker praises the charitable items on a London merchant’s will:

Besides large Legacies to not a few of his neare kindred and acquaintance, which I cast out of this account. To the poore Palatine exiles, fifty pounds: to the Towne of Leicester for the use of the poore Weavers and Knitters there, fifty pounds: for the reliefe of poore prisoners, one hundred pounds: for the taking up in the streets a certaine number of poore children, Boyes, and Girles, to be fitted for, sent out to, and placed in the forraine Plantations, three hundred pounds: among his poore servants, seventy pounds: among other poore, left to the discretion of his Executors, fifty pounds: to this poore man, and that poore Minister, as they came then in his minde, to the summe of forty and seven pounds; which in all amounteth to six hundred sixty and seven pounds.

This for his charity, [g] as fresh at last as at first, notwithstanding his charge, that is wont to coole charity with many, but did not so with him.

With the rise of imperialism, it is interesting that sending poor children of both sexes who live on the streets to live and work in the colonies is considered a charitable act–a mark of a changing era. Instead of preparing the children to be apprentices within the city, they are to be sent off overseas instead.

While exploring phrases by keywords is fascinating, they require looking into their original contexts in order to be meaningful. Because these sermons have abundant printed annotations in their margins that include citations of Biblical passages mentioned within their texts, we can compare keywords phrases with charity-related scriptural citations. In the “Biblical Citations In Sermon Marginalia” page, we introduce our motivations, methodology, and results from extracting, standardizing and visualizing the distribution of scriptural citations in the margins of relevant sermons. Particularly, we show how we can identify clusters of texts by the density and distribution of the the passages of the Bible that they cite, and how we can use citations to identify strands of discourse around the topic of charity in the charity sermons dataset.

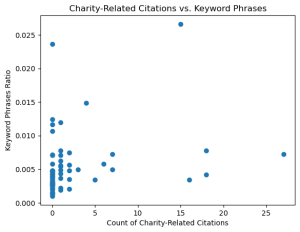

Upon comparing the results from both, we see that there is a weak positive correlation (r2: 0.074084, r: 0.272184, p-value: 0.022639) between the number of charity-related scriptural passages cited in the margins and ratio of keyword phrases over the length of the text. Because some texts are a single sermon whereas others are much longer compilations of several sermons, we have to take the ratio of keywords phrases over text length instead of looking at the raw counts. With a p-value of 0.022 and a test of significance at 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis that texts with more of our keywords do not have more charity-related citations. However, the low r-squared value suggests that calculating a line of best fit is not a good model for the data, which is explainable by most of the points clustering at the lower left. We find that texts with high numbers of charity-related citations do have a higher proportion of keyword phrases, but not vice versa. Many texts with high ratios of keywords have very few, if any, corresponding citations.

References

“1601: 43 Elizabeth 1 c.2: Act for the Relief of the Poor.” The Statutes Project, 6 Oct. 2016, https://statutes.org.uk/site/the-statutes/seventeenth-century/1601-43-elizabeth-c-2-act-for-the-relief-of-the-poor/.

Craig, John. “Sermon Reception.” The Oxford Handbook of the Early Modern Sermon, edited by Hugh Adlington et al., Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 0. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199237531.013.0010.

Eales, Jacqueline. “Whately, William (1583–1639), Church of England Clergyman and Puritan Preacher.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/29178.

Green, Ian. “Preaching in the Parishes.” The Oxford Handbook of the Early Modern Sermon, edited by Hugh Adlington et al., Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 0. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199237531.013.0008.

Kelliher, W. H. “Crashawe [Crashaw], William (Bap. 1572, d. 1625/6), Church of England Clergyman and Religious Controversialist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6623.

Lincoln, Margarette. London and the Seventeenth Century: The Making of the World’s Greatest City. Yale University Press, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/duke/detail.action?docID=6455824.

McCabe, Richard A. “Hall, Joseph (1574–1656), Bishop of Norwich, Religious Writer, and Satirist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/11976.

Moore, Jonathan D. “Preston, John (1587–1628), Church of England Clergyman.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/22727.

Rigney, James. “Sermons into Print.” The Oxford Handbook of the Early Modern Sermon, edited by Hugh Adlington et al., Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 0. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199237531.013.0011.