If one searches for press about the Duke University Musical Instrument Collections, this 2001 article from Duke Today is most likely to appear first. It details the contents of the instrument collection that G. Norman and Ruth Eddy donated to Duke, in the year that it posthumously arrived on campus. Surviving epistolary sources from Norman demonstrate, however, that the collection’s donation was first confirmed in 1977. At that time Norman described the paintings in his collection as being 20 in number, and by 2001 that number had risen to 90. These paintings, completed in Norman’s own hand and often depicting restored instruments from the collection, demonstrate a connection between the artistic influences reflected in the painting style, the art of preserving instruments, and the broad ethos of the Eddys’ decision to maintain a collection. The inclusion of these paintings in the collection is not only unique, it also sheds light on Norman and Ruth’s intentions for its use at Duke: a pedagogical and organological tool unlike anything of its kind in the American Southeast.

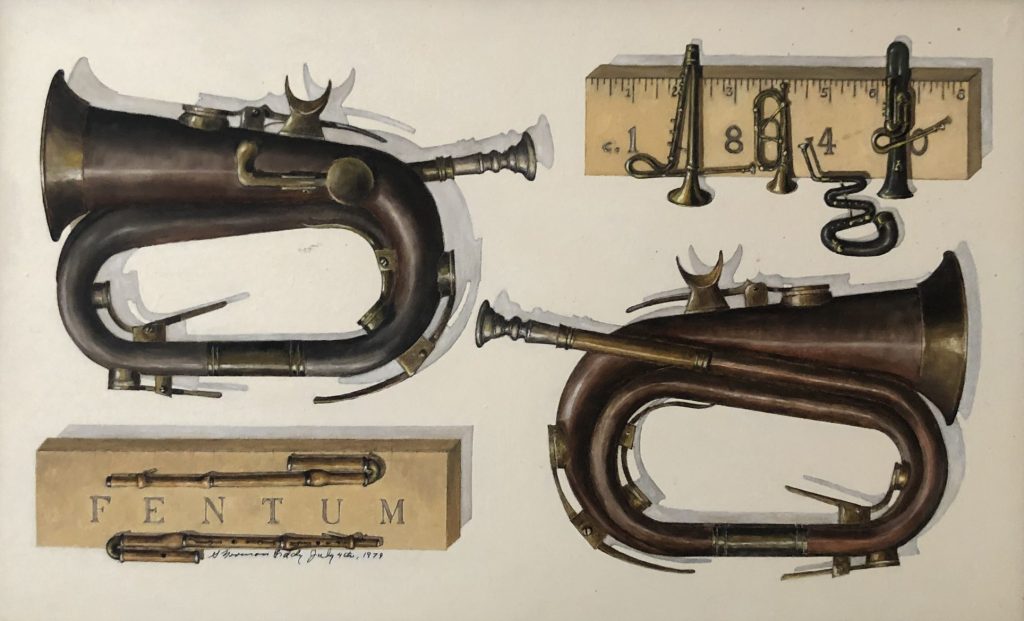

The above image is one such representation of G. Norman’s paintings. The detail in the small, isolated pieces of the deconstructed clarinet are immediately striking, as are the cutaways on the assembled clarinet to the right and the eight-inch lizard sitting atop the ruler at the bottom. As is indicated, the painting depicts a clarinet by the maker Hermann Werde (1770–1841), though there is a disagreement between Norman and Edwin M. Good (1928–2014), the collection’s cataloguer, about the specific date of the instrument. Good also curiously describes the lizard as having “no significance except to suggest that even wooden artifacts have a certain life.” While there does not seem to be any particular association between the animal, the instrument, or the maker, it does appear that Norman had an affinity for adorning otherwise commonplace and utilitarian tools. The below painting is another example, where the eight-inch ruler is accompanied by several early iterations of brass instruments, most notably a serpent.

These two paintings are similar in both artistic style and practical use. The prominent shadows that appear underneath the instruments themselves give a sort of illusion most commonly associated with the trompe l’oeil style. The shadows imply that a light is shone on the image and makes them look somewhat three-dimensional. It is also somewhat unclear if the instruments are lying flat on a surface or hanging on a blank wall. This style had a resurgence in the later nineteenth century, when artists like William Michael Harnett (1848–92) used it for similar effect. In his 1888 Violin and Music, pictured below, the same figural disorientation is displayed, though the nails that hold the bow and string provide a more grounded perspective than either of Eddy’s paintings.

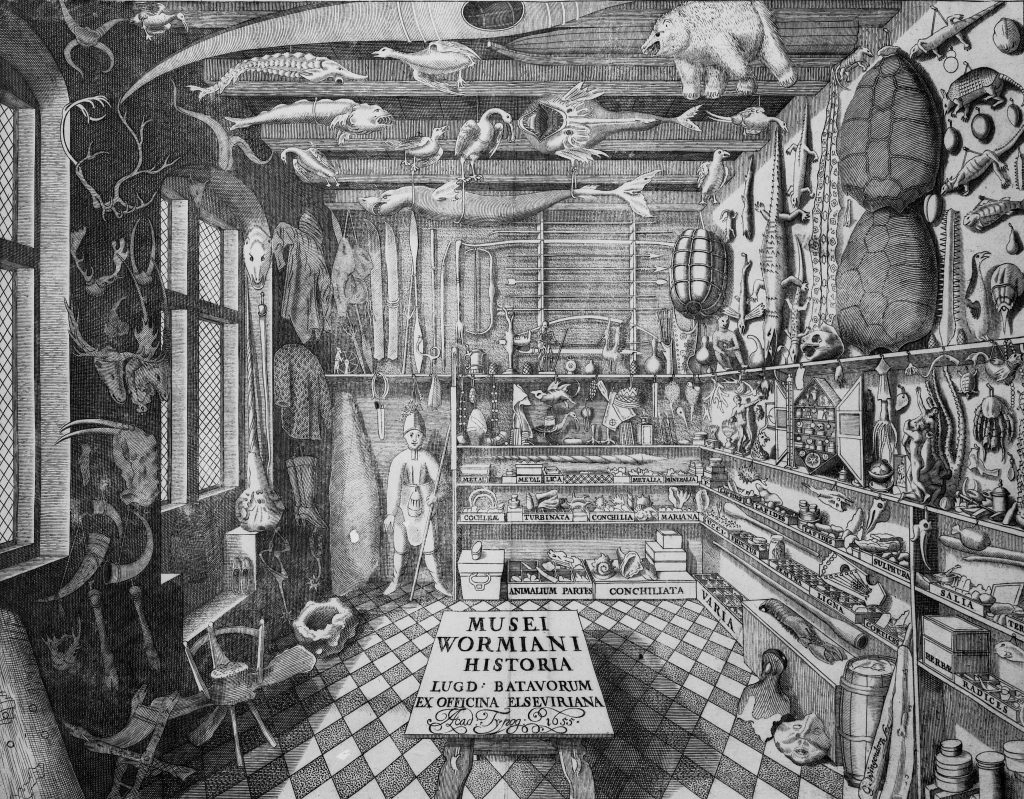

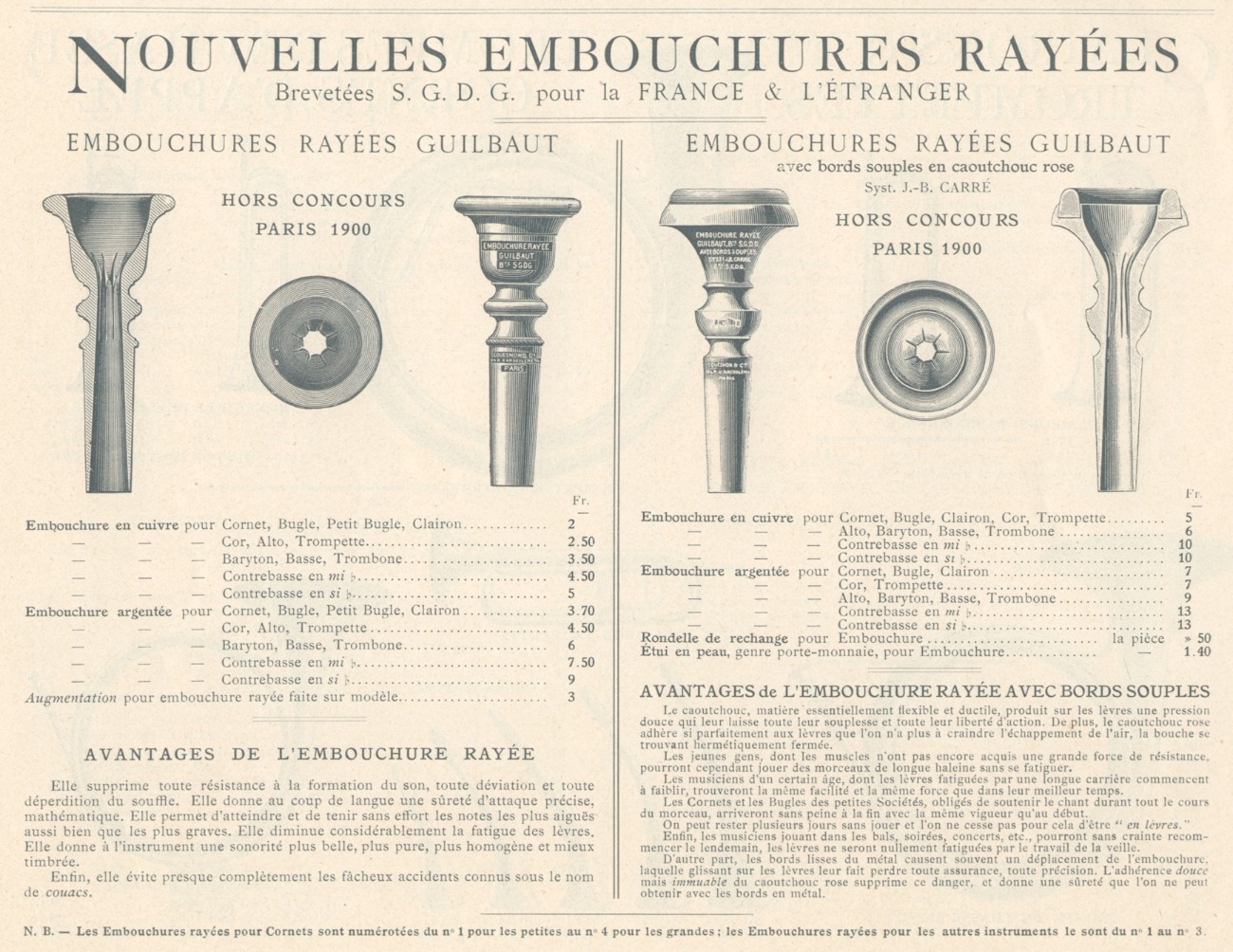

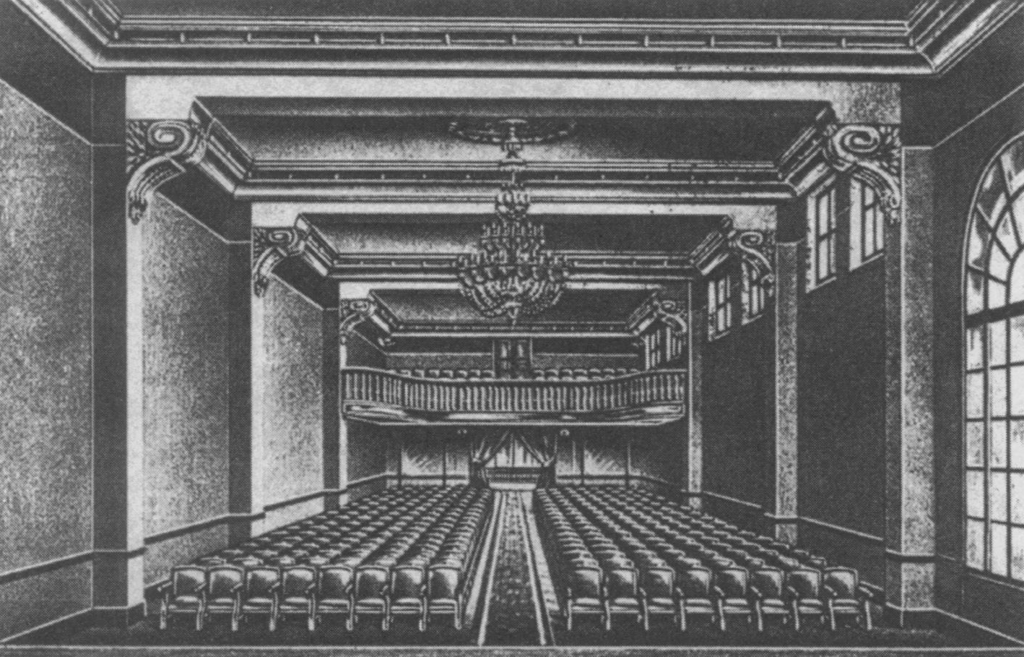

The lifelike and three-dimensional quality of the instruments in Norman’s paintings is reminiscent of two dominating artistic genres often associated with the early-modern period: still lifes and curiosities. Both genres focus on the display of themed items that interact with one another within the frame, and often incorporate items that analogize death, prosperity, intelligence, or some such. As can be seen in the Baschensis still life (below), the collection of diverse stringed instruments highlights their shapes and resonances. Worm’s Museum is notable not only for the collection of animals considered “exotic” during his lifetime, but also because of the use of perspective; it appears that a large sturgeon, a bear, and a set of antlers are all equal in size. Both examples are represented in Norman’s paintings, but in different ways. His clarinets and bugles use a similar “point of light” that casts shadows from a particular angle in still lifes, while the depiction of uncommon animals for the sake of highlighting exoticism is abundant in this particular curiosity.

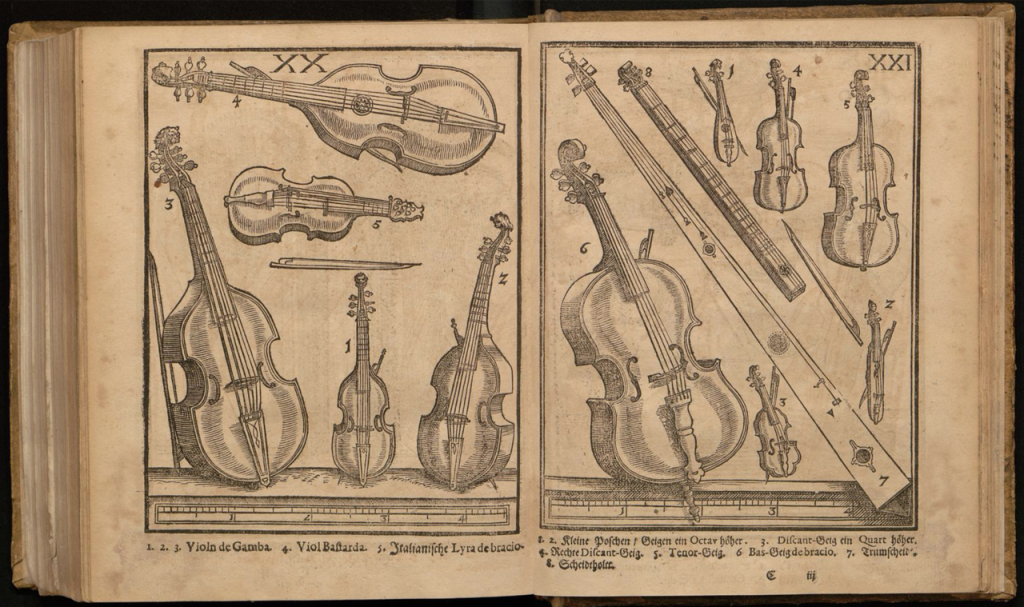

The ruler in Norman’s paintings is unique for its adornments, but it also represents a long history of instrument sketches. Michael Praetorius’s 1619 Theatrum Instrumentorum is a notable connection because of Praetorius’s use of the “Brunswick foot.” As shown below, the printed book provides illustrations of instruments to scale, based on the ruler at the bottom of the pages. Musicologist Matthew Zeller has translated Praetorius’s inscription for the ruler: “[The Brunswick foot] is the correct length and measure of a half Schuh or foot according to the ruler, which is a quarter of a Brunswick Ell; and according to this, all of the drawings of the instruments that follow have been adjusted to the little ruler always set with them” (138). While Praetorius’s ruler is comprised of five sections and Norman’s displays eight inches, they are otherwise similar in their ability to portray the sizes of instruments and their proportion to one another.

Norman’s ruler showcases particular artistic genres and historical precedent, but it also highlights the ethos of the Eddy’s donation of their collection to an academic institution. In Norman and Ruth’s 1977 letter to Terry Sanford, then President of Duke University, they stated their wish “to commit our antique musical instrument collection, paintings, and supporting materials to Duke University … as we believe very deeply in the future of Duke, its musical arts programs, and in the capital campaign to add to the strength of the University.” At the time Duke’s music department was developing a graduate program for musicology, and in a 1981 memo to Chancellor Kenneth Pye, Dean Craufurd Goodwin noted that the collection “would be an essential basis for courses in ‘organology’—the study of ancient instruments.” In a separate 1981 memo between two Duke employees, the collection was described as being of “interest to the general public and to students,” and that “interest in the arts … in the southeast could be further developed” with the collection being housed on campus. Both Norman and Ruth did indeed have an interest in cultivating organological study in a part of the country that did not already house a well-known instrument collection, like in New York or Boston.

While the ruler reflects influences from artistic genres, its primary use to depict instruments to scale demonstrates a pedagogical orientation. Many of the paintings were completed soon after the respective instruments in the collection had been restored. Norman’s creative output, then, is associated with his work as a restorer and collector, as well as his aims to provide an institution in the Southeast with a robust collection for study. That this representation is present within Norman’s paintings, some completed two decades before their eventual donation to the university, speaks to the Eddys’ long-standing intention for their collection to continue its life in the hands of students.

By Nick Smolenski, Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology, Duke University

with thanks to Dr. Matthew Zeller for his help