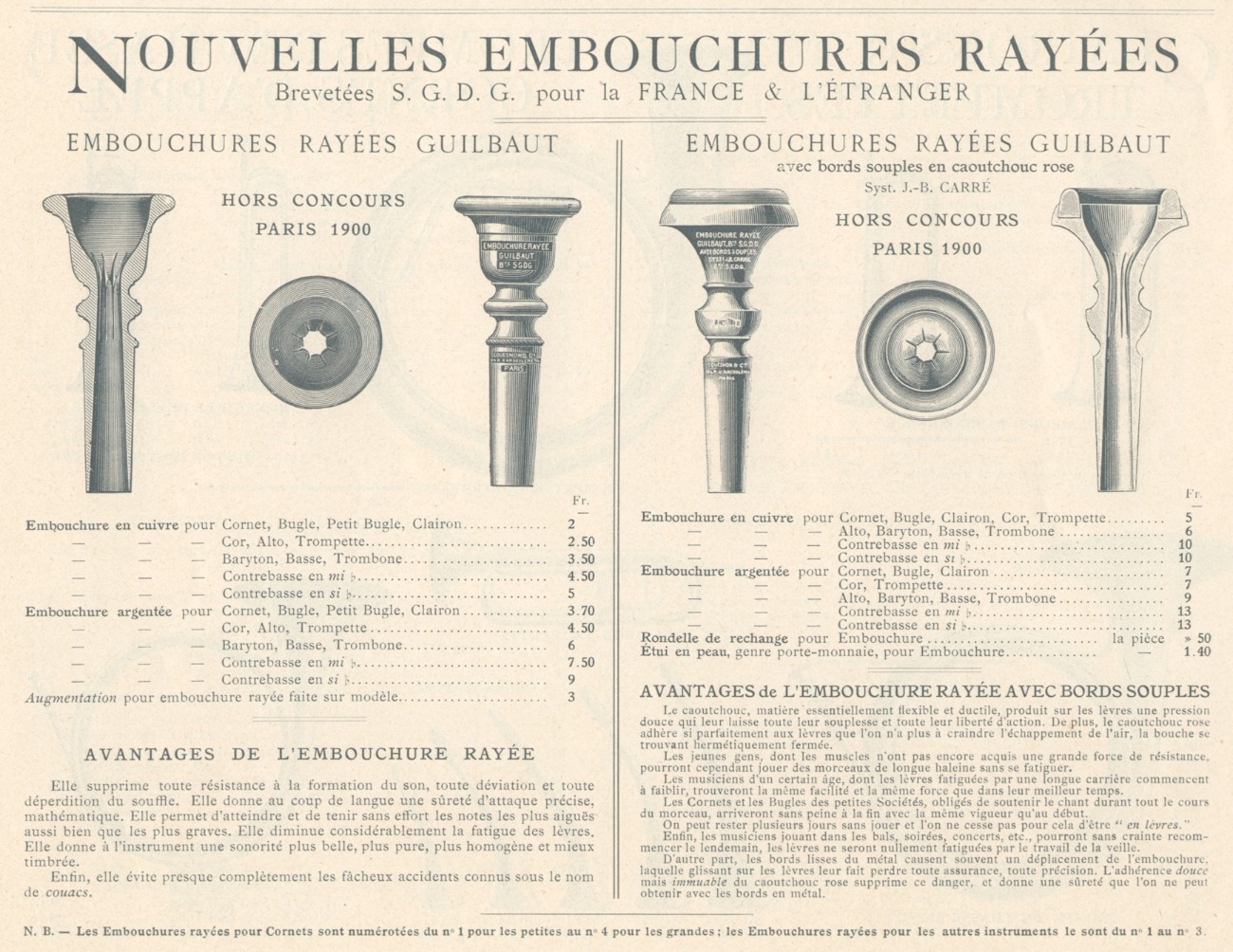

E. Guilbaut is somewhat of an historical enigma. Despite his high-profile accomplishments at the turn of the twentieth century—named President of the “Association des Cornettistes de Paris” and the inventor of the “embouchure rayée,” or groove-throated mouthpiece—little else is known of his history. Guilbaut developed his mouthpiece at Couesnon & Cie, considered the most famous musical instrument company in the Western world by the end of the nineteenth century. An entry from a surviving Couesnon catalog (shown above) promotes the grooved mouthpiece as a new and fundamentally improved tool for any brass player of any skill level. Curiously, this revolutionary adaptation disappears entirely in Couesnon catalogs from 1910 and is never featured again, though groove-throated mouthpieces have continued to be developed by other instrument makers (even in the present day). Guilbaut’s name vanishes as quickly as the grooves themselves, and thus the Couesnon cornet mouthpiece in the DUMIC collection can be dated ca. 1900–1910.

While Guilbaut produced a number of groove-throated mouthpiece models, one in particular stands out from the others because of its soft rubber rim (“bords souples en caoutchouc rose”). The width of the metal rim, underneath the rubber, is about as wide as other Guilbaut cornet mouthpieces. As the above photos show, the rubber creates a narrower rim, privileging flexibility and range over endurance. The cup and throat are also quite narrow, which creates a brighter tone and relieves fatigue. The grooves in the throat help to minimize resistance and encourage more lip vibration, expanding range and broadening tone quality in the process. According to Guilbaut, these effects were caused by the grooves directing air more immediately through the throat and backbore, rather than it circling within the cup and creating additional resistance.

Couesnon’s catalog details how the new groove-throated mouthpiece was advertised to the average consumer. The rubber rim was promoted not only for comfort, but as a pedagogical aid. Younger players “whose muscles have not yet acquired great resistance” will find that the mouthpiece helps to produce the necessary level of resistance while simultaneously alleviating lip pressure, a bad habit which often leads to poor technique. Couesnon also reaches out to professional players and older novices, suggesting that fatigue and inaccuracy is a thing of the past. They allude to its universal application in musical settings by listing balls, parties, and concerts as ideal events to play on the mouthpiece. While they are not listed, outdoor events such as processionals, parades, and military events would have also been ideal considering the shape and material of the mouthpiece.

If the mouthpiece was as ubiquitous as the catalog suggests, why did Couesnon cease production in less than a decade? While sales are what ultimately drive or stall production—I suspect this case is no different—the company’s history and successes provide a more holistic explanation, namely that Couesnon had the resources and creative fortitude to experiment with new technologies. By 1900 Couesnon & Cie was known across Western culture as an award-winning brand in quality, accuracy, and innovation of musical instruments. Guilbaut’s groove-throated, rubber-rimmed mouthpiece just happened to be an innovation that was short lived.

Couesnon was initially established and named after Auguste Guichard in 1827 before Pierre Gautrot, brother-in-law to Guichard, took over as proprietor in 1845. The company opened its first factory in Château-Thierry in 1855, and by 1890 it employed over 200 instrument makers (the largest musical instrument factory at the time). Business partners and company names changed periodically until 1882, when the business opened a factory in Paris and became permanently known as “Maison Couesnon.” Historian Thomas Le Roux details how its social and architectural prominence contributed to its role as a leading innovator of brass, percussion, and woodwind instruments. Amédée Couesnon, son-in-law to Pierre Gautrot, was CEO when the company was awarded a gold medal at the 1889 World Exhibition in Paris, celebrated especially for their instruments’ “good quality and accuracy.” By 1900 Couesnon was asked not to compete in the Exhibition because they had swept whole categories each year. Amédée was later knighted by the Légion d’Honneur in 1893 before assuming the position Officer of the Academy in 1895. Couesnon & Cie expanded to eleven factories in 1911, while Amédée’s son, Jean Couesnon, facilitated the company’s partnership with Columbia Phonograph Company in the United States, thus cementing its international legacy before its steady decline caused by the 1929 market crisis.

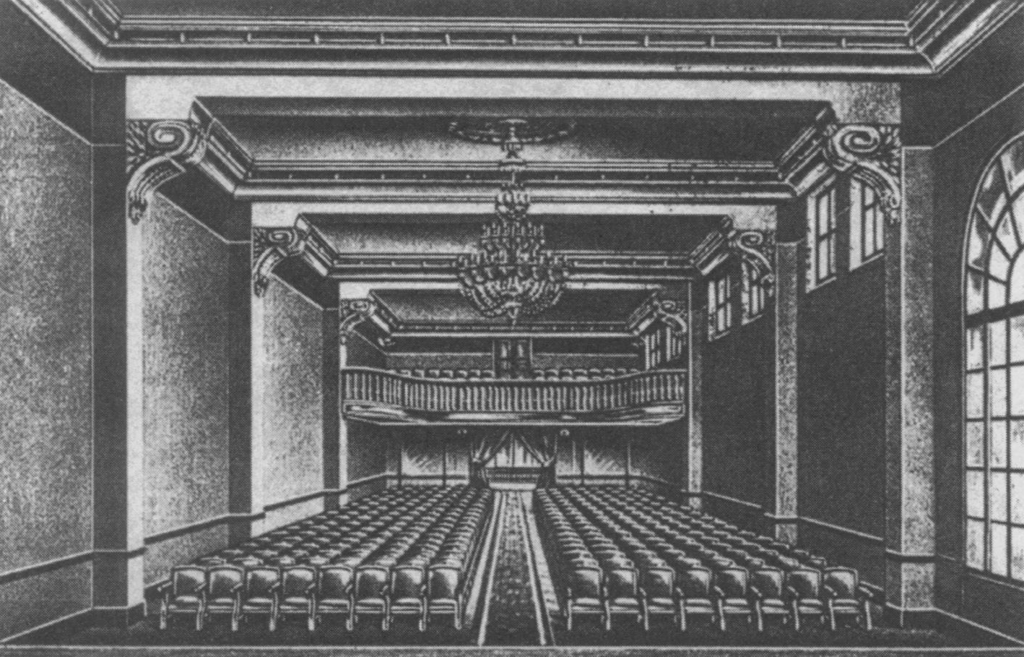

Maison Couesnon’s most visible and celebrated factory was located in the 11e Arrondissement of Paris (94 Rue d’Angoulême). In the first decade of the twentieth century the factory expanded to two buildings, complete with a covered hall and a courtyard between them. The second building became Couesnon’s lavish “La salle de l’harmonie,” within which orchestras would perform concerts and musicians could test their instruments in a controlled acoustical setting. Le Roux notes that the hall and courtyard became important spaces in which social classes uniquely intermingled throughout each season. Maison Couesnon thus became a cultural epicenter as well as a site for quality craftsmanship.

With this company history in mind, Guilbaut’s “embouchures rayées” can be viewed as a representation of musical invention at a time when Couesnon was at its financial and cultural height. Even though Maison Couesnon was asked not to compete in the World Exhibition because of their winning so many awards, they were still allowed to present new models and promote their products. Couesnon became the gold standard for brass instruments in particular; hiring staff to cultivate new techniques like the grooved throat was paramount to their continued success. The legacy of the groove-throated mouthpiece is integral to understanding the impact Couesnon had on the greater musical instrument industry. While Guilbaut’s mouthpiece was short lived, the technique was picked up by other instrument makers in post-war America and continues to be developed since its invention over a century ago. That a single mouthpiece can illustrate the cultural and creative impact of a French instrument company speaks to the profound influence of the elusive Guilbaut.

By Nick Smolenski, Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology, Duke University