Our project extends researchers’ powers by making scientific collaborations with computer tools — an increasingly important engine of research enterprise — easier, while also protecting data from being exposed. We seek to rejigger the balance of ease-of-access and privacy protection.

We have focused on building out new means of federating research applications, and over the life of our grant we have extended the concept of “CoCoA” applications. In a sense, we’ve cooked up a richer CoCoA, while keeping constant with the fundamental innovation that the original CoCoA laid out.

What is CoCoA?

In the main, “CoCoA” (“Comanage+Conext+Applications”) has focused on web-based applications, even though “a set of domain tools” could also imply a non-web or more “systems” platform (see this description of CoCoA). The most obvious examples are wikis and shared calendars, as Internet2 points out. CoCoA applications listed by SURFnet (surf.nl; Netherlands) are web-based and quite broad in scope, including “business management,” collaboration, video, and security.

CoCoA is an acronym composed from two perhaps unhelpfully named (and partially acronym’ed) technologies (COmanage and Conext, now OpenConext). But central to CoCoA is the ability to federate access to applications, and the process of rendering (or converting) an application for this manner of consumption on the web is called “domestication.” SURFnet provides a useful definition:

Domestication is described as the process of externalizing authentication, authorization and group management from applications. Domesticated application[s] typically use a[n] external authentication source like for example a SAML based identity federation, and communicate with group management and authorization systems to retrieve additional information on the authenticated user, his/her roles and rights.

Domesticated applications enable single sign-on features for users, as well as the ability to share group context between multiple applications. From the service provider point of view, externalizing identity and group management eases the burden of maintaining these kind[s] of account data.

Federating access is the defining goal, but a problem is having the right things to access

In some sense, having the right things in place for researchers is an issue of history and of habit. Researchers want to dive into their data with tools they know and that have a real relevance and credibility in their disciplines. The trouble? They can’t wait for some tools to be “domesticated” on the web in order for them to become part of the federated universe.

That match of web tool and research task is often delicate, and can get in the way of adoption of web-based and domesticated tools — they are less familiar at least, even though they may be functionally the same as the shrink-wrapped product on the PC.

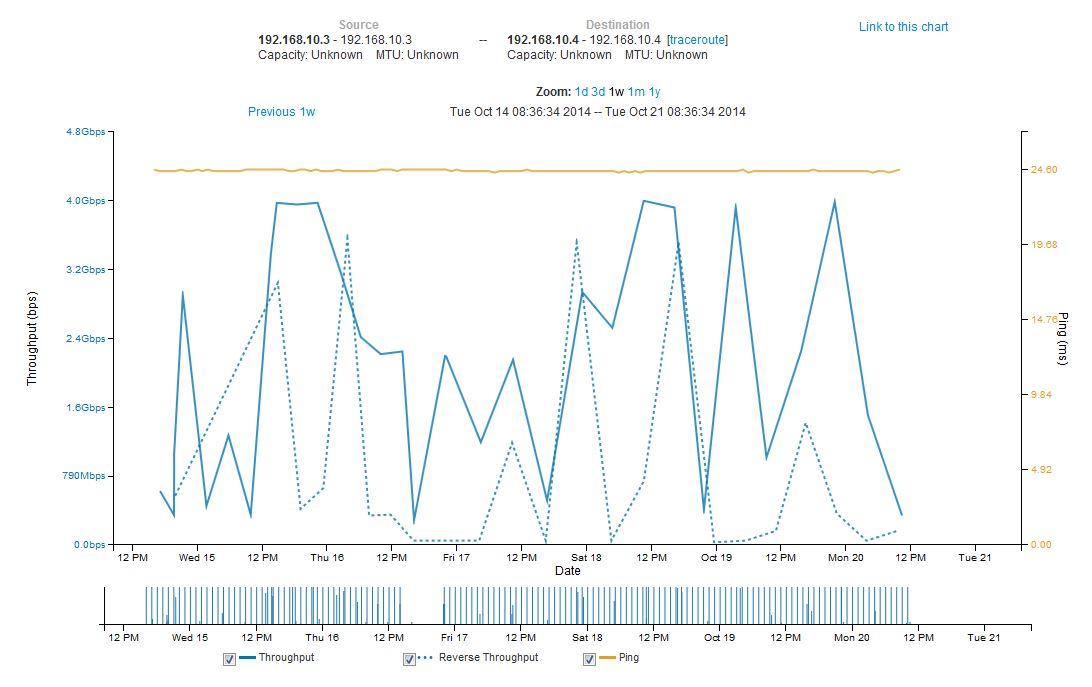

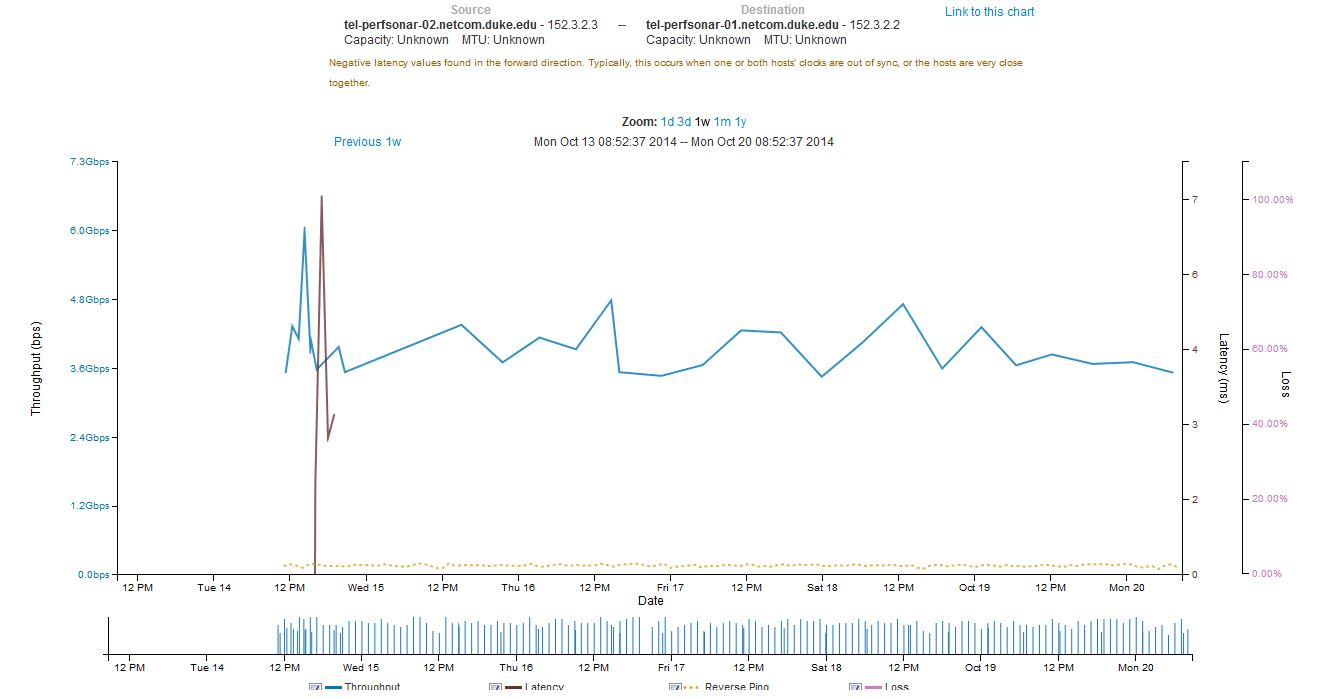

The tactic that we have taken in “domesticating” whole operating system platforms removes some of the trouble — sociological or psychological though it may be — by placing the federation and authentication steps prior to entry into what is, after all, a familiar place: a Windows or Linux desktop. Though that familiar sight appears within the context of a modern web browser, the feel is familiar and research applications work as usual, as Linux or Windows applications. We have found that the graphics performance is quite acceptable, especially for users who are on Duke campus networks. Even Youtube works, albeit soundlessly since we have not worked on passing audio through the middleware layers that do the tricks.

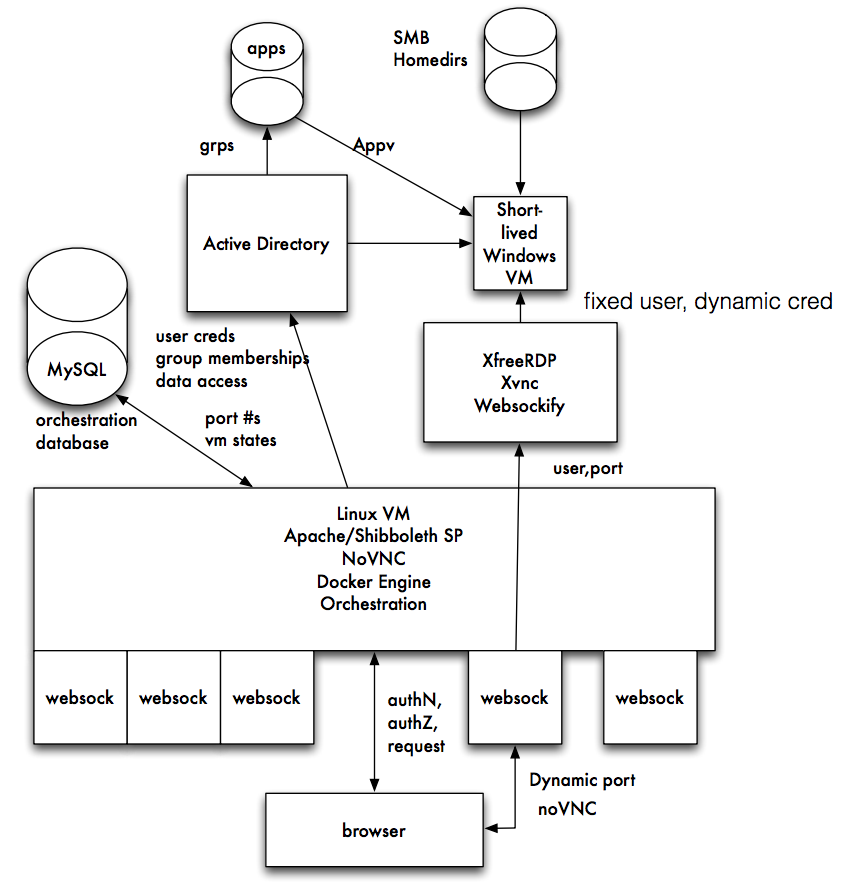

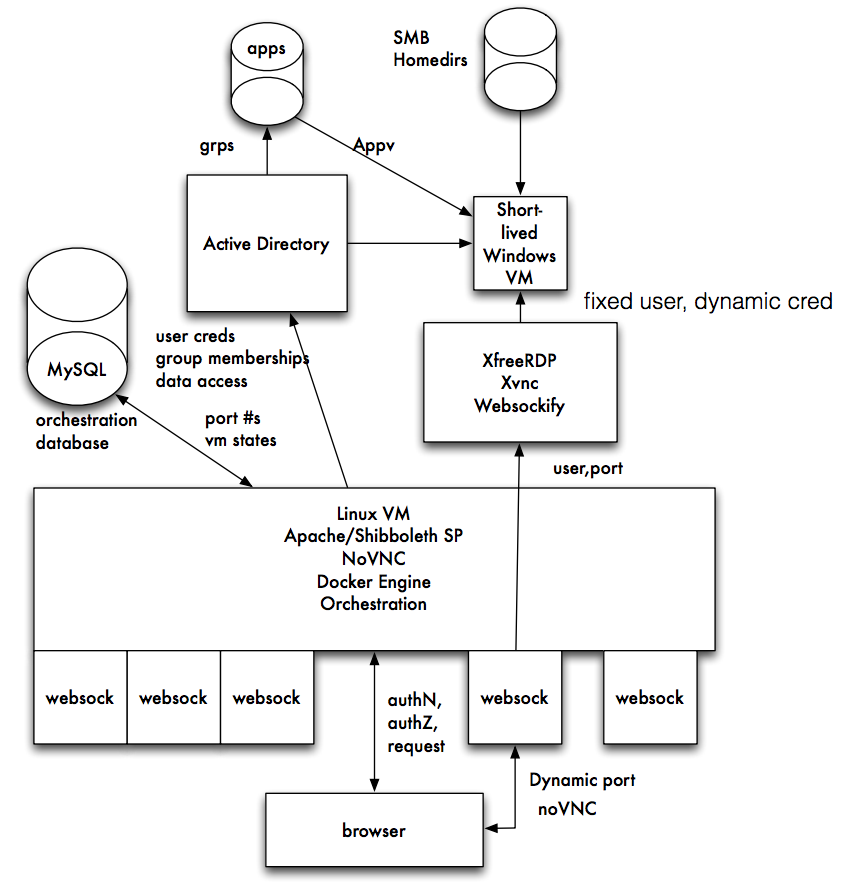

In a sense, the domestication we have accomplished relies more on glue than on hand crafted parts. Tools already available position the operating system so that displays can render desktops in a modern web browser. The glue is rather complex, as this graphical representation of a system for domesticated Windows machines illustrates:

(That schematic appears in a presentation Rob Carter made at Internet2’s Technology Exchange in October 2015. See Federated, Remote, Clientless Windows Access for the complete set of slides.)

(That schematic appears in a presentation Rob Carter made at Internet2’s Technology Exchange in October 2015. See Federated, Remote, Clientless Windows Access for the complete set of slides.)

The process goes like this:

- A user from University A points her web browser (at the bottom of Rob’s illustration) at a page to gain access to a Windows VM offered by University B

- University B determines whether the user qualifies for access by seeing whether University B counts her as OK, either by consulting internal records or rules and asking University A to confirm the user’s credentials (Rob’s “authN, authZ request”).

- University B maps the user to a temporary username on a virtual machine and passes the desktop of that machine through a system using RDP and VNC to render the desktop to the user in a web browser. The user’s claim on the virtual machine will persist, but the credentials for access to the virtual machine is unknown to the user.

- Storage resources required by the user are made available to the temporary user on the Windows machine.

- At the close of the session, records of the session are kept, but the temporary username and credentials are destroyed. The virtual machine (now inaccessible with the destroyed credentials) is retained for a certain period, so that the state of the machine persists and can be accessed by the user — though using another set of temporary credentials created for the next session.

One thing that is notable — aside from users witnessing the oddity of seeing a complete Windows desktop in a web browser — is that the authentication mechanisms on the web/client side actually are not directly tied with the authentication mechanisms of the Windows machine. That is, user credentials for access via the web (where the federation takes place) are different from the credentials operating on the Windows machines. In the Duke implementation, Windows-side credentials don’t even persist, but may be limited to single session. Credentials may live beyond a single login session to allow for long-lived calculations to complete. That connection of authenticated user and user-on-the-machine is done by the glue and by mechanisms that Rob has created to map the Real and Persistent User with an ephemeral counterpart on the Windows machine.

Rob called an early version of the system “Schaufenstern” for good reason: the system separates the “outside” from the “inside” by a sheet of glass, metaphorically speaking, through which you can see but which also prevents direct interaction. (Schaufenstern is German for display windows or shop windows.) That separation has security benefit, for by separating the mechanisms of authentication and coordinating them by other back-end means, computers can be shielded from exploits like “Pass-the-Hash” which exploit the persistence and transmission of credentials in networked Windows systems.

The set up for Linux machines is similar, though a bit simpler to deploy. Mark McCahill has done that, and the system has been in operation for some time now, with hundreds of instances (Docker-ized, of course!) serving both researchers and students.

Another CoCoA, maybe this one a bit tastier

Very fancy, you might say. Very fancy to see quickly deployed and personalized machines appear in web browsers. But how does this make my CoCoA more flavorful?

The point of CoCoA, at its most basic, is to ease collaboration across distances among people who can share common sets of applications. The fundamental resources for that have been developed using the Internet and web technologies, mainly because they are now ubiquitous and are so woven into the practices of research and scholarship. Also, administrative arrangements (constituted in Internet2, for example) have normalized the expectations and many of the tools that underlie trust transactions. Technology and trust together make “federated” authentication feasible.

But feasible doesn’t mean that anyone would want to do it, and thus the range of applications — the “A” in CoCoA — have to be compelling.

We know that researchers of all stripes use computers, and they share data and scripts so that they can experience and witness each other’s work on computers in a sort of rudimentary “collaboration.” We also know that many applications that researchers value have not yet themselves been domesticated for the web — and thus made in scope for federated access on the web.

Our work steps behind the application and in effect domesticates whole sets of applications by making their context — the operating system and its user desktop — the domesticated thing.