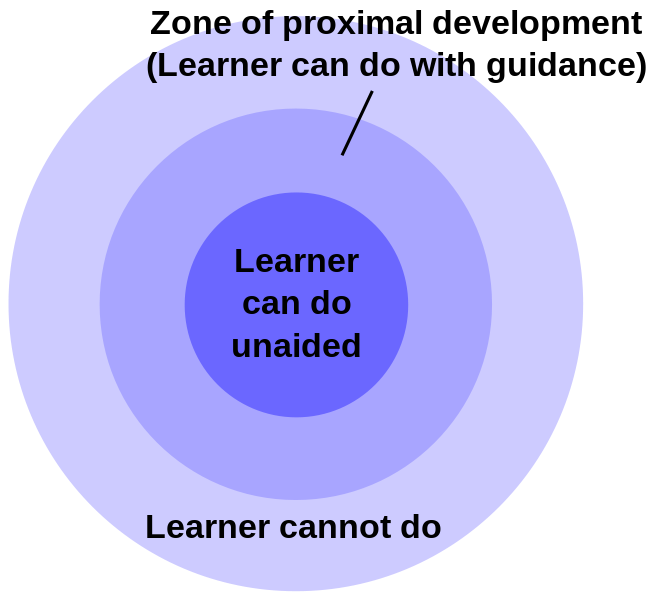

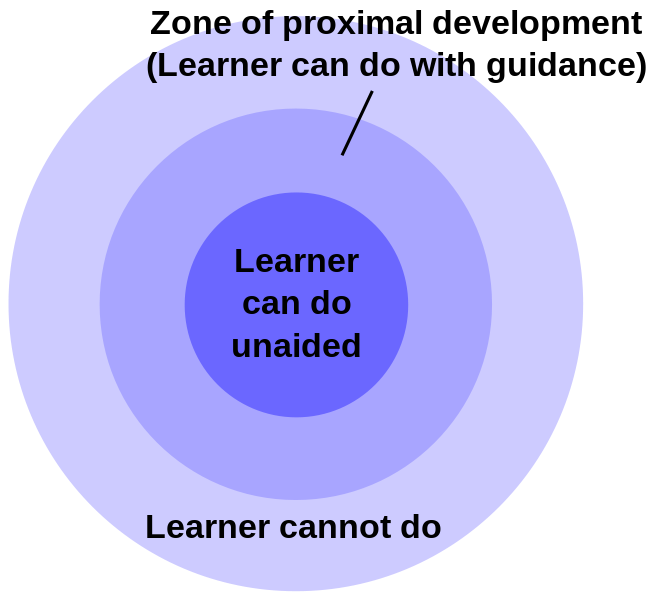

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is an idea from Lev Vygotsky. It represents what a learner can do when given sufficient help. See below for a diagram explaining it.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_of_proximal_development

In essence, there are three areas (or zones).

-

- What a learner can do without help.

- ZPD – What a learner can do with help.

- What a learner cannot do, regardless of how much help they receive.

Vygotsky originally developed this idea while studying children’s cognitive development and within the context of social interactions. However, we can still apply it to our own learning settings. The ZPD is where learners are provided scaffolds to help them succeed. Scaffolds are support “structures” that help a learner succeed. They come in many forms, such as a teacher pointing out pertinent information, asking critical questions, and nudging a learner in the right direction, or a homework that starts with simple questions using a single concept and then progresses to more complex questions that use multiple concepts. Over time, this scaffold is slowly removed or fades away, such that the learner can complete the task independently. Once they are independent, this moves the learning objective (i.e., the thing they are learning) from the ZPD into the “learner can do unaided” zone.

Differentiating whether Help is Scaffolding

When it comes to receiving help on a task that is intended to support achieving a learning objective, it’s important to consider whether that help is scaffolding the learning process. One way to do this is to assess how germane that help is to the learning objective. The way to assess help’s germaneness is by considering how much of that help/support needs to be faded away for the learning objective to be achieved. If that help were not available, would the learner have been in the zone of “learner cannot do”? Notice that the question centers around the learning objective, not the task that the person does to help them achieve that learning objective. Here is a concrete example:

-

- Task: Draw a picture of your dream house.

- Learning objective: Apply key techniques to create a drawing that accurately depicts perspective.

- Help germane to the learning objective: Giving direct instructions on where to place a ruler to draw line guides or stating where vanishing points should be.

- Help not germane to the learning objective: Offering ideas for potential dream house features, such as what colors to use.

The help’s germaneness to the learning objective is not necessarily black and white. For example, offering ideas that would make the drawing easier, such as giving feedback on reducing the number of windows so it’s easier to draw, could be germane to the learning objective. It would depend on the context and could require a judgment call between the learner and the teacher.

Whether the help is germane does not determine whether the help is “bad” or “good” for the learner’s learning. Once again, it will depend on context. The primary question is whether the help would prevent the learner from achieving the learning objective. Is the help scaffolding the learning such that it will/can be properly faded, and eventually the learner can work independently? For example, asking a tool to always place the line guides means the learner never practices making the judgment call of deciding where the lines go. While a teacher would be aware of how often the learner asks for such help and carefully fades it away, or has a direct conversation with the learner if they see overreliance on that help.