It has been mentioned that the first (in the world) Chekhov monument, which was estabished in Badenweiler in 1908, was soon melted down, the Chekhov Salon brochure reports (http://www.literaturmuseum-tschechow-salon.de/de/schriftsteller.html?file=files/litmus/pages/schriftsteller/broschueren/museum-GB-200516-webs.pdf). With many delays (apparently related to various political crises), a stone was eventually put up to replace it in 1963. I did not find this stone so it would be unfair to post a picture of it here, but you can find everything in the brochure link. What compelled me more was the story of Georgi Miromanov, who was director of the Chekhov Sakhalin Book Museum in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk on Sakhalin Island

(for details, scoot down a couple of posts). Having recently visited this museum I felt personally invested in the story. Some time after 1985, Miromanov promised Badenweiler that he would give the city a new monument by 1990 in time for the 130th anniversary of Chekhov’s birth. Considering that there are at least nine time zones difference between the two locations, not to mention 7374.557584 miles (11,868 .2 kilometers), plus, inevitably, such factors as world politics and money, this would seem to be a difficult promise to keep. And yet, as the brochure reports, in the fall of 1990 Mironamov, together with his son and the sculptor Vladimir Chebotaryov,

(for details, scoot down a couple of posts). Having recently visited this museum I felt personally invested in the story. Some time after 1985, Miromanov promised Badenweiler that he would give the city a new monument by 1990 in time for the 130th anniversary of Chekhov’s birth. Considering that there are at least nine time zones difference between the two locations, not to mention 7374.557584 miles (11,868 .2 kilometers), plus, inevitably, such factors as world politics and money, this would seem to be a difficult promise to keep. And yet, as the brochure reports, in the fall of 1990 Mironamov, together with his son and the sculptor Vladimir Chebotaryov,

arrived in Badenweiler in an old army truck with the new memorial which they had declared scrap metal at the various borders they had crossed on their arduous way from the Pacific Ocean.

It was a journey worthy of Chekhov’s own trek in the reverse direction in the spring and summer of 1890 (take note, it took place on the centennial of that journey). And my comfortable, leisurely trip by train to Sakhalin in 2019 is a faint tribute, as I now learn, not just to Chekhov but to Mironamov. Who has chronicled the bureaucratic, financial, and logistical obstacles this new statue faced along its way? I am reminded of other journeys that cover some of this itinerary, such as the 2015 Rally Rodina trip undertaken by four guys on Ural motorcycles:

(https://www.maximprivezentsev.com/rally-rodina)

also highlighting Chekhov’s trip and book (there’s a movie). And others people have taken, not always even leaving a trail. According to the Chekhov Salon brochure, this was the first Russian monument in Germany after the collapse of the Soviet Union, which reminds us that that FIRST Badenweiler Chekhov monument was the first Chekhov monument in the world. (Let us hope that THIS one will not be melted down to make bullets. Politicians are always threatened by the voices of artists). In short, Chekhov fans, keep your eyes on Badenweiler. Having overcome all physical, economic, and political obstacles in his way, having achieved his goal of restoring a Chekhov monument to Badenweiler, Miromanov suffered a martyr’s fate: on his way back to Sakhalin, reports the brochure, while passing through SUMY, Ukraine (a Chekhov hot spot and place of great creative activity that was on my itinerary until February 24, 2022), Mironamov died of heart failure.

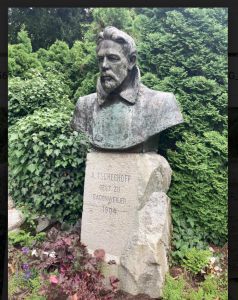

This monument stands just below Badenweiler Castle on a very high hill overlooking the German countryside, which you have walked up. The pilgrim follows a clear trail of signs along the footpath until the statue gently appears in view on the hill above you

.

.

Appropriately, for our hero, who was himself a passionate gardener, it stands above a nice little garden, teeming with flora and fauna (salamanders, two small white butterflies in love, a throng of invisible buzzing insects, and a placid, golf-ball-sized snail).

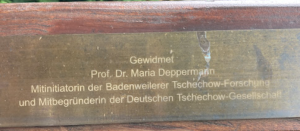

A generous Chekhov reader (one of the many quiet heroes in this story) has set up a bench here where you can sit and breathe the fresh air and look over the view that someone very thoughtful thought up for you and Chekhov to contemplate.

Sitting here on the bench, one continues to ponder matters of spirit–the word’s origin in  breath–respiration, for which we are particularly grateful on this stop on our journey, and its place as the origin of art–inspiration, and, we hope, of healing. In addition to the monuments in stone and bronze, in photographs and street-and-square names, Badenweiler also offers up a monument in spirits, a Tschechow wine, a gentle red, with which you can nurture your own on the Katharina terrace, upon your descent from the hill to dry land .

breath–respiration, for which we are particularly grateful on this stop on our journey, and its place as the origin of art–inspiration, and, we hope, of healing. In addition to the monuments in stone and bronze, in photographs and street-and-square names, Badenweiler also offers up a monument in spirits, a Tschechow wine, a gentle red, with which you can nurture your own on the Katharina terrace, upon your descent from the hill to dry land .

Leave a Reply