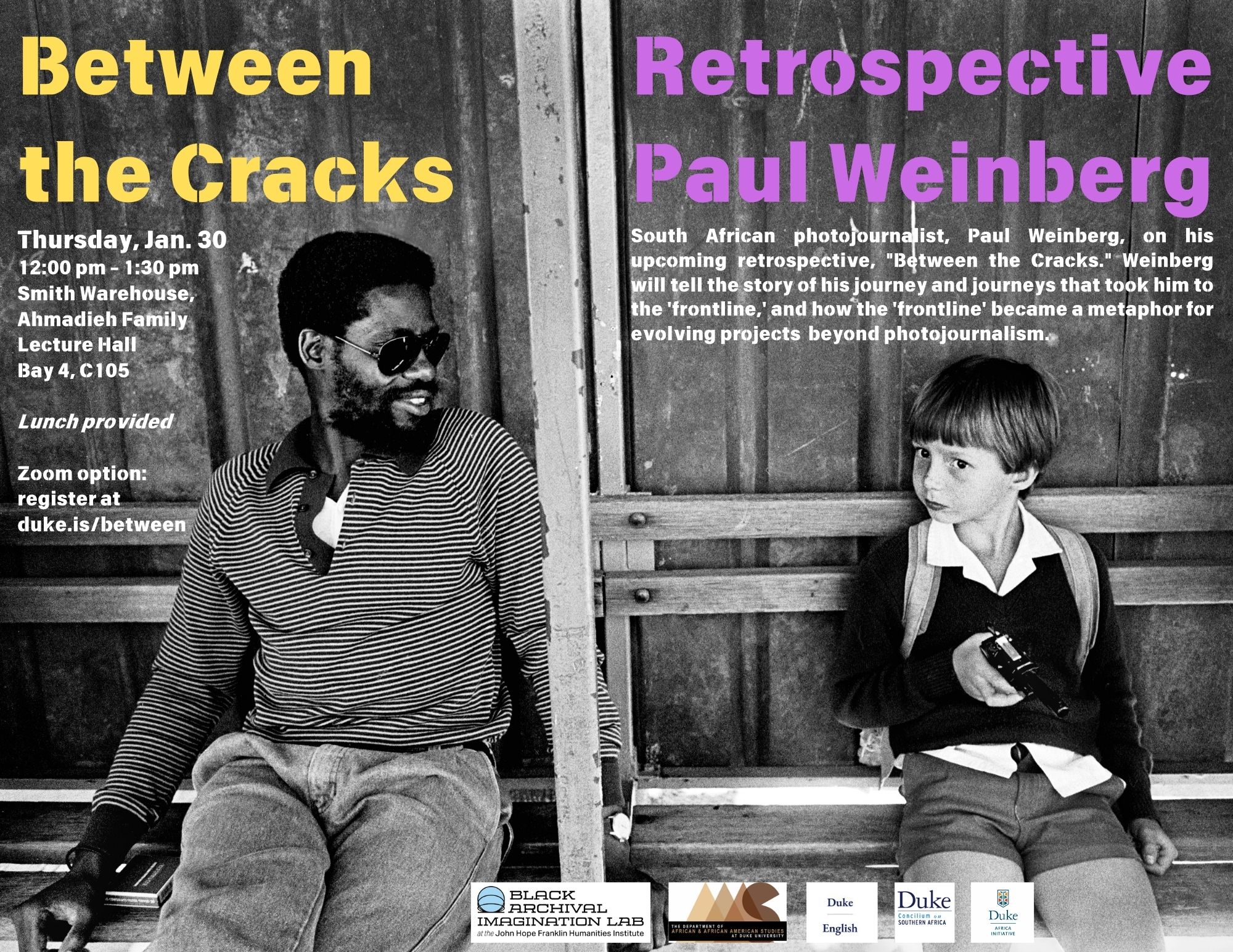

An event featuring South African photojournalist, Paul Weinberg, on his upcoming retrospective called “Between the Cracks.” He will tell the story of his journey and journeys that took him to the ‘frontline,’ and how the ‘frontline’ became a metaphor for evolving projects way beyond photojournalism.

Thursday, Jan. 30

12:00 pm – 1:30 pm EST

Duke Univ., Smith Warehouse, Ahmadieh Family Lecture Hall, Bay 4, C105

Lunch will be available for attendees.

Zoom option: register at https://duke.is/between

“Between the cracks, life continues with its pain and joy. During the “dark days”, apartheid shadowed me on all these journeys. It was always there consciously or not. It was in the lines of people’s faces or in the fascist bravado of military parades and numerous events echoed their presence. But it was the people I was looking at – watching how they reflected themselves and how I absorbed their reflections, how they danced with reality, how they made light in a dark space, how they embraced each other at great risk.” – Paul Weinberg, Travelling Light

“Photography became an integral part of how I was seeing the world; it gave me a passport to travel across the divides that were so prevalent at the time, and I used to go on all sorts of trips off the beaten track. I would enter the townships, hitch-hike, catch trains – anything that would break the mould of white and black, and whatever kept us divided. And the camera gave me a wonderful opportunity to explore and try to understand the world around me.” – Paul Weinberg, Then and Now

Bio:

Paul Weinberg is a South African-born photographer, filmmaker, writer, curator, educationist and archivist. He began his career in the late 1970’s by working for South African NGOs, and photographing current events for news agencies and foreign countries.

He was a founder member of Afrapix and South, the collective photo agencies that gained local and international recognition for their uncompromising role in documenting apartheid, and popular resistance to it. From 1990 onwards he is increasingly concentrated on feature rather than news photography. His images have been widely exhibited and published, both locally and abroad. He also initiated several major photographic projects, notably Then and Now, a collection of photographers from the collective photographic movement of the 1980s, Umhlaba, a project on land and The Other Camera about vernacular photography in South Africa.

In 1993 Weinberg won the Mother Jones International Documentary Award for his portrayal of the fisherfolk of Kosi Bay, on South Africa’s north coast. He has taught photography at the Centre of Documentary Studies at Duke University, and Masters in Documentary Arts at UCT. He currently works as an independent curator, archivist and photographer.

Background Information from Paul Weinberg:

“Making photography a career came to me unexpectedly. But when it came, it felt just right – a perfect tool to dance my way through the contested and turbulent South African landscape.

I bought my first camera at 11 years old. I became the official family holiday photographer and dabbled at high school in photographic and darkroom technique. But it was a hobby, a sideline activity.

Like all young white South African males of my age, I was conscripted into the South African Defence Force. My brother who had done his service a few years before as a storeman at Voortrekker Hoogte, advised me to ‘go and get it over and done with’. I had grown up in a liberal political household. My parents were members of the Liberal Party until it was banned in 1968 due to its multi-racial membership and its one person, one vote vision.

After finishing high school, I was conscripted into the South African army in 1974 and unlike my brother ended up in the infantry, an experience that was to shape my life and career. I then went on to study law at University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. Half-way through my law degree the 1976 Soweto uprisings happened. Fully aware that conscriptees like myself would be used to do apartheid’s dirty work, I abandoned law, registered as a conscientious objector and went to study photography, thinking that if I had to, I could leave the country with a skill. I then headed for Johannesburg where I thought I could disappear. For 10 years I avoided being arrested by the military and security police. I didn’t pay tax and lived like a refugee in my own country. My passport was always close at hand in case I needed to leave the country. It was a phase of my life where I fought back with my camera. Those early survival days turned into a career.

I have been a photographer for 45 years and have produced 20 books in my own right, either as a photographer, or author and photographer. I have also been involved in many collective projects, exhibitions and publications. I was a founder member of Afrapix and South collectives. Many associate me with the problematic term ‘struggle photography’. My life’s work has been vastly more nuanced and diverse than that. While I have been ‘witness’ to many key moments in southern Africa’s history, I would describe myself as a reluctant war and rebellious news photographer. Most of life’s work has been ‘beyond the news’ and engaged in in-depth visual story telling. I have always looked for the less obvious, predictable portrayals of society and without sounding pretentious, drawn to the lyrical.

I have taken many long and protracted journeys from the bush to the city and all that lies in between. I spent a period of 30 years documenting the ‘modern day’ San of southern Africa. This documentation culminated in a book called Traces and Tracks. For a period of 3 years I lived intermittently with and documented the fisherfolk of Kosi Bay as they struggled to hold on to their land rights and way of life. This project won the Mother Jones International Award. I have followed people working the land for decades, often living in close proximity to wildlife areas. This project became a book and exhibition called Once We Were Hunters.

In 1994 I was the official photographer for the IEC and witnessed intimately our historic birth of democracy. Land has been a central focus of my life’s work, people working the land and their relationships to it. After 1994 I embarked on a project called Back to the Land, documenting the return of resettled communities back to land. In a way both these projects closed the circle signified by the shadow of apartheid of which I observed through my camera in multiple ways for about 15 years.

Since then, I have been concentrating on projects that are mostly about celebration, in-depth and personal. Key projects in this period have been Moving Spirit, where for 10 years I documented rituals of spiritual practice; Durban, a portrait of an African City; Dear Edward, a book and exhibition about my family roots, where I turned the camera on myself; Musings in Muizenberg, a book about beach culture in the place where I now live; and most recently EarthSongs which explores landscapes of spirituality and dovetails with the earlier project Moving Spirit.

When, in the early 2000s, the bottom fell out of the world of photojournalism, the medium on which I was, financially dependent, I embarked on a career which was intuitive from very early on – working with the archive. In recent years I have worked professionally as a curator and archivist. It has been challenging and invigorating work, but in many ways it has also left me with major challenges. I consider archival work, particularly in South Africa, as a kind of cultural heritage activism. Much like how we viewed our work as photographers at the height of repression during apartheid, each archive that is conserved and digitally preserved, I view as a victory against amnesia and cultural neglect.

In recent times, my creative expression has also been articulated through video. I have made a number of documentaries with colleagues on issues as diverse as slavery, indigenous music and other aspects of life in South Africa. My archival work, film, and photography coalesce comfortably for me in that they are all part of a broader rubric of storytelling. Not only do stories break down barriers of race, class and geography, they are vectors in pursuit of understanding our individual and collective journeys as humans in this world. And, on a personal note, stories that animate neglected spaces and histories, encourage me to do more. ‘Story’ is a necessary practice in a country like ours with such a difficult past and in desperate need of healing. In that sense I remain as motivated as ever to continue the journey of storytelling that I began many years ago. That journey continues ..”.