Nimen Hao! and Good morning!

I am delighted to be welcoming you to Duke Kunshan University on behalf of the faculty. “Delighted?” Perhaps not the right word. No, I feel something more akin to what the ancient Greeks would label deinos, a feeling associated with human regard for things too strange or divine or complex to comprehend, a word that connotes a great deal of respect, even reverence, and more than a little bit of awe or even fear. We see this word in the first half of dino-saur, literally a “deinos lizard.” In American slang, the adjective that leaps to mind is awesome, and so perhaps I should best say that I am both delighted and awed to welcome you on behalf of the DKU faculty. This is an awesome undertaking, and yes, not so unlike a dinosaur, large and impressive, something to respect, even reverence, hard to wrap your mind about as a being —and a bit scary too.

My name is William Johnson, and I am a Professor of Classical Studies at Duke. Classics or Classical Studies in the West means the study of ancient cultures around the Mediterranean, and the term “Classics” implies in particular study of the ancient Greeks and Romans from roughly 800 BCE through to about 300 CE. I am, in particular, a scholar of ancient Greece — its language, literature, history, and culture.

The two most common questions about DKU that I get asked —and I assume the same is true for my faculty colleagues— are: (1) why is Duke interested in starting a campus in China? (2) why are you interested in it?

Why Duke in China? Answers of course will be many and multiform for such a complex undertaking, but tend to center around issues like the importance of China on the world stage, China’s burgeoning economy, its interest in further development in areas like management, science, health, together with Duke’s strength in areas like business, science of all kinds, and global health. In more vague and general terms DKU can be described as an extension of the global strategy that Duke now embraces. These are all important. But in my view, a more essential answer could well flow from what happened just now, in the simple act of my introducing myself. Think about what happened there. I could not assume, as I could in America or England or Italy or Germany, that even a highly educated audience would know what “Classics” or “Classical Studies” meant. Moreover, I had to position this as what is classical in the West, since I am well aware of the fact that there is a very different classical in the East, with a very different notion of the ancient that one looks back to — and by implication the beginnings that one looks back to. Ancient philosophy suggests not Socrates and Plato, but Confucius; ancient empire brings to mind not the Persian and Athenian empires but the Qin and Han dynasties; ancient historiography begins not with Herodotus and Thucydides but Sima Qian; the birth of drama means not Greek tragedy but early Chinese opera. So, I have to specify what it means that I am called a Classicist, since I am not a student of what is classical or even ancient from any but a Western viewpoint.

Now that may seem a small thing, but it’s a big thing, a very big thing, deinos as the Greeks would say. In the West, when we sketch out a rough developmental history of what we call the cosmopolitan perspective, that history runs something like this: at first people identified with their family and kinship group (a person might say, “I am one of the Alcmeonidae, a powerful Greek family”). As societies developed civic institutions, that identity could then embrace not just the family clan but a tribe or a city (“I am an Athenian, one of the Alcmeonidae”). After the conquering of much of the Mediterranean and Near East by Alexander the Great, identity shifted to include all those who spoke your language and had shared cultural traditions (“I am a Greek, an Athenian, one of the descendants of the Alcmeonidae”). Then as nations developed, identity could center on the national impulse, which is essentially cultural but also territorial (“I am an American, a Greek American, who speaks Greek and English, and whose parents came from Athens and claim to be from a prominent family”). Note how in each developmental turn, the perspective becomes wider: one can now be American, even if Greek in heritage and in language, and ultimately from Athens, which, however, like the identification with a family of prominence, is at a remove. This is an increasingly cosmopolitan outlook, with all that flows from that, but it is still very much rooted in the Western perspective.

Duke’s global initiative in general, and DKU in particular is, by this analysis, another turn of the screw. In order even so much as to introduce myself, I have to step away from my comfortable Western assumptions about who I am (a “Classicist”) and come to grips with the fact that Classics should be a more embracing term, and that only from a blinkered or even half-blind vision can words like “classical” and “ancient” reasonably denote only ancient Greece and Rome. The possibilities for global collaboration at DKU will be rooted in particulars, like management and science and health and archaeology and humanistic inquiry, but underneath all this is a much larger issue: the potential for working out shared visions and mutual understandings that lead, on both sides, not only to engaged interactions but to the development of a more cosmopolitan viewpoint that, however, remains rooted in the particulars of who we are and where we come from (one might say,”I am an educated person, a citizen of the world, though, yes, also an American, Greek by heritage whose family is said to have come from a once-powerful family in Athens”). The DKU undertaking has potential, then, that is truly deinos, huge, dynamic, complex, something to respect, to nurture, to admire, an undertaking that in its sweeping possibilities truly inspires awe.

Now as to the second question, What is my interest in DKU? that will be a more personal matter for each of the faculty. Part of my own answer I have already given: I am very excited by the possibilities of DKU, and I too want a share in this fresh cosmopolitan view. Moreover, like several of the faculty, I have close personal ties to China.

At bottom right of the collage at left is our “yoga baby,” my daughter, Benita Xiaogu, on the very evening of her adoption in August 2003, in Guangxi Province. (Benita is now twelve years of age, and you will see her around.)

But we decided to adopt in China for good reasons, and high on the list was a deep interest in coming to know and be a part of this other ancient culture — that is, a culture of similar antiquity to the Greeks and Romans we had studied for our Yale doctorates (my wife Shirley Werner is also a Classicist; you will see her around too).

That these two independently forming ancient civilizations — the Mediterranean peoples on the one hand, and “China” on the other — may have an interestingly larger story to tell than the individual histories they offer is easily seen. I hope that some of the details of that will come out in the course I am teaching, but we can use a visual image to demonstrate quickly how interesting an exploration of parallel antiquities can be.

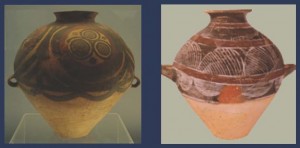

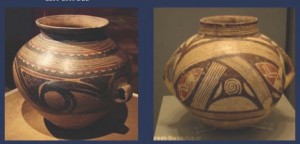

At the far left is an ancient Chinese pot that resides in a museum not far from us, in Shanghai, which comes from around 2000 BCE. Beside it, at the right, is another ancient pot, this one from the Lerna in the Peloponnesus area of Greece, a pot imitating the so-called Minoan Culture, from roughly the same time. Below are two other neolithic pots, the left from China, the right from Greece. There are differences one can point to, but the similarities are striking, to say the least.

What interests me, as a cultural historian, is what narrative or narratives one might create from this parallel. The story that this goes back to an unknown cultural exchange in the neolithic period has been proposed, but is widely rejected by scholars. More tenable, and considerably more interesting, might be to ask questions like, why is it that in ancient societies, advances in pottery techniques seem to go along in parallel with other advances like the development of civic institutions, such as villages and cities and legal systems, or even more sophisticated formations such as empire. And why does this development include not only formal advances such as the ability to make larger or lighter pots, but also refinement of artistic technique and aesthetic beauty, which seems to move along a path from geometric to figured representation? Even this small example exposes at once, then, why I as a scholar of the ancient Mediterranean find ancient China so very intriguing, and why I find interesting the opportunity to bring to a class in China the narratives of how the Greeks are said to be the “originators” of culture in the West.

What interests me, as a cultural historian, is what narrative or narratives one might create from this parallel. The story that this goes back to an unknown cultural exchange in the neolithic period has been proposed, but is widely rejected by scholars. More tenable, and considerably more interesting, might be to ask questions like, why is it that in ancient societies, advances in pottery techniques seem to go along in parallel with other advances like the development of civic institutions, such as villages and cities and legal systems, or even more sophisticated formations such as empire. And why does this development include not only formal advances such as the ability to make larger or lighter pots, but also refinement of artistic technique and aesthetic beauty, which seems to move along a path from geometric to figured representation? Even this small example exposes at once, then, why I as a scholar of the ancient Mediterranean find ancient China so very intriguing, and why I find interesting the opportunity to bring to a class in China the narratives of how the Greeks are said to be the “originators” of culture in the West.

As you will have noticed both from the course catalogue and my remarks here, I have a deep interest in beginnings, and I wish in closing to focus on that aspect of the DKU undertaking. I have recently been reading a fascinating account of how road systems and the metaphor of journey influenced ideology and thought in China’s classical era. All journeys, real or metaphorical, have a beginning, of course, and in the classical era in China it was usual to start one’s journey with elaborate ritual and prayers. As it happens we have one splendid example of prayers for the road from that era. It runs,

In a felicitous year and a good month, an auspicious day and a fortunate hour, may you be very happy when you set out in the light of dawn…. May you mount the chariot and have the road open before you. May the Wind Monarch and the Rain Legions wet down the road [to reduce the dust]. … May the Green Dragon travel at your side. May the White Tiger help you advance. May the Vermillion bird [the sun] lead you. May Xuanwu [god of night and darkness] be your companion. … May you have joy without end.[1]

Now for a student of ancient Greece, when one reads of the traveler’s chariot and the divine companions, what springs to mind is another poem, by the early philosopher-poet Parmenides, a poem which seems almost naturally to follow the Chinese prayer. That runs:

It is the mares that bear me, as far as my heart desires, as the divine maidens place me upon the auspicious path of the Goddess, a path that can carry a man with understanding as far as the stars. Thereon am I borne, as the wise mares strain to pull the chariot … with the maidens, Daughters of the Sun, hurrying to escort me, having left behind the House of Night for the light, pushing the veils from their heads with their hands. Ahead are the gates of the paths of Night and Day … and straight through them did the maidens drive the chariot and mares, along a large and open road. The Goddess received me kindly, took my right hand in hers, and spoke to me: “Youth, attended by immortal charioteers, you who come to our House by these mares that carry you, welcome. For it was no bad fortune that sent you forth to travel this road (lying far indeed from the beaten path of humans), but Right (themis) and Justice (dikê). And it is right that you should learn all things….

An auspicious day, an auspicious path indeed. On behalf of the faculty, then, it is with great pleasure that I say, “let it now begin.”

William A. Johnson, Professor, Duke University and interim Chair of Faculty, DKU

[1] From Michael Nylan, “The Power of Highway Networks during China’s Classical Era (323 BCE–316 CE): Regulations, Metaphors, Rituals, and Deities,” in Highways, Byways, and Road Systems in the Pre-Modern World (edd. S. Alcock, J. Bodel, R. Talbert, 2012) 33-65.

威廉–约翰逊教授在开学典礼上的发言稿

你们好!早上好!

我很高兴代表全体教师欢迎你们来到昆山杜克大学。“高兴”?也许不够确切。我现在的感受更类似于古希腊人用“deinos”这个词所表达的含义,一种人类在面对非常陌生、或神圣、或复杂得难以理解的事物时的情感。这个词带有非常多的尊敬、甚至是崇敬,还有不少的敬畏甚至是害怕的意思。英文“dino-saur”(恐龙)的前半部分就源自于这个词,就是“恐怖的爬行动物”的意思。在美国俚语里,最接近的形容词就是“awesome”(令人敬畏的,极好的),所以我或许应该这样说:我很高兴而且很“敬畏”地代表全体教师欢迎你们加入昆山杜克大学。这是一个令人敬畏的事业,跟恐龙其实有相似之处,庞大而令人震撼、值得尊敬甚至敬畏,一种超乎一般人想象的存在。当然了,也有一点吓人。

我叫威廉-约翰逊,是杜克大学的古典研究教授。西方的古典学或者古典研究指的是对环地中海古代文化的研究,而“古典学”这个名词特指对公元前800年到公元300年之间的古希腊和古罗马的研究。我本人是研究古希腊的学者,包括语言、文学、历史和文化。

关于昆山杜克大学,经常有人问我这两个问题,估计其他的教授也是一样被问到。这两个问题是:1.为什么杜克大学有兴趣在中国办学?2.为什么你本人对此有兴趣?

杜克为什么来到中国?对于这样一个复杂的事业来讲,答案当然有很多,但都基本围绕在中国在世界舞台上的重要性、中国蓬勃发展的经济、中国致力于在管理、科技、医疗卫生等领域的进一步发展,而杜克大学恰恰在商业、各种科技领域和全球健康方面处于领先地位。用更抽象和概括的说法,昆山杜克大学可以被看做是杜克大学现在所坚持的全球化战略的一个延伸。这些都是很重要的原因。但是从我个人的角度,通过我刚刚自我介绍的简单方式就可以得到一个更关键的答案。想想刚才发生了什么。我不能够像在美国、英国、意大利或者德国那样想当然地认为听众会明白“古典学”或者“古典研究”是什么意思,尽管听众们都是接受过高等教育的。不仅如此,我还必须指出这是“西方”对古典学的定义,因为我非常清楚在东方对“古典学”的定义是非常不同的,而且对于“古代”的概念也是不同的,也意味着对于“起点”的定义是不同的。在中国,“古代”哲学指的不是苏格拉底和柏拉图,而是孔子;“古代”帝国让人想到的不是波斯和雅典帝国,而是秦朝和汉朝;“古代”史学的先驱不是希罗多德和修昔底德,而是司马迁;戏剧的“诞生”指的不是希腊悲剧,而是早期中国戏曲。所以我才必须明确指出我被称为一名古典学者的含义,因为我仅仅从西方文化的角度研究,而并不是从事其他文化背景下的“古典”或者“古代”研究的学者。

这也许看起来没什么大不了的,但其实这是非常非常重要的,希腊人会说是很“deinos”的。在西方文化里,如果要概括我们称之为“国际化视角”的发展简史,差不多应该是这样的:最初人们的身份取决其所属的家庭和家族(某人会说:我是Alcmeonidae家族的成员,一个强大的希腊家族)。随着社会发展出市政机构,则人们的身份不仅仅取决于所属的家族,还包括所在部落或者城市(“我是雅典人,Alcmeonidae家族成员”)。在亚历山大大帝征服了地中海和近东的大部分地区后,身份的认同转变为包括所有跟你说同一种语言并有着同样的文化传统的人(“我是希腊人、雅典人、Alcmeonidae家族后裔”)。然后随着国家的发展,身份认同就带上了国家的色彩,本质上是以文化为划分的主要依据,但也可以以领土划分(“我是美国人、希腊裔美国人、说希腊语和英语、父母来自于雅典,据说祖先是名门望族”)。请注意,每一次的发展变化都让视角变得更宽广:虽然是希腊后裔、说希腊语、先辈来自于雅典,但这个人还可以是美国人。然而,祖先是名门望族这类的身份认同已经消失了。这就是一种越来越国际化的视角,尽管覆盖面极广,但基本上还是根植于西方文化的视角。

总体来讲,杜克大学的国际化战略,尤其是昆山杜克大学的建立,根据上述分析,是国际化视角的进一步拓展。即便是做简单的自我介绍,我也必须放开我已经习惯的关于我身份的西方定义(“一名古典学家”)并且认同“古典学”这个名词应当有更加宽泛的含义,把“古典学”和“古代”这样的名词含义局限在古希腊和古罗马的范畴是以偏概全、坐井观天的做法。在昆山杜克大学开展的全球合作将基于具体的学科,比如管理、科学、医疗、考古和人文等等,但这些都建立在一个更广义的问题之上:合作建立共同的理想并相互了解,进而让双方开展合作,并建立一种更加国际化的视角,但同时仍然根植于我们不同的个体以及所代表的国家和文化(一个人可以说:“我是一个受过良好教育的人,一个世界公民,但同时我还是一个美国人,希腊后裔,祖先据说在雅典曾经是名门望族”)。这样的话,昆山杜克大学就有可能成就真正“deinos”、伟大、充满活力、复杂、令人尊敬、值得鼓励、值得仰慕的事业,一个会带来无限可能性的真正让人敬畏的事业。

关于第二个问题,我到底为什么对昆山杜克大学感兴趣?每个教师的答案都会见仁见智。我已经给出了我答案的一部分:我对昆山杜克大学未来所能够带来的各种可能性感到非常兴奋,而且我本人很希望都够享受到崭新的“国际化视野”。此外,跟几位其他的教师一样,我和中国有着很亲密的关联。屏幕中间显示的就是我们喜欢称之为“瑜伽宝贝”的我女儿的照片,她叫贝尼特-晓顾,这是在2003年8月领养她的那个晚上照的,地点是中国广西。(贝尼特今年12岁了,你们会经常看到她的。)我们当初决定在中国领养孩子是有很多原因的,其中重要的一条就是对中国古老的文化有着浓厚的兴趣,并且希望投身其中。中国文化与我们夫妇在耶鲁攻读博士期间所研究的古希腊和古罗马同样源远流长。(我爱人雪莉-维尔纳也是一名古典学者,你们也会经常见到她的)。

显而易见,地中海文明和中国文明这两种独立形成的古代文明除了各自璀璨的历史之外,有着令人着迷的共同点。我希望通过我在昆山杜克大学讲授的课程来呈现一些具体的细节,但我们可以通过视觉影像来快速展示对平行的古代文明进行研究是多么有趣。屏幕的左上角是展示在离我们不远的上海博物馆里的一件中国古代陶器,年代是公元前2000年。现在我给你看另外一件古代陶器,来自于古希腊伯罗奔尼撒半岛的莱尔纳,是仿效大概处在同一历史年代的迈诺安文化的陶器。下面是两件其他石器时期的陶器,左边是中国的,右边是希腊的。我们可以找出其中的差异,但是其相似程度让人惊诧。作为一个文化历史学家,让我感兴趣的是,人们会如何去解释这种平行文化的相似度。有种理论说这是因为早在石器时代,这两种文化间就有了某种不为人知的交流,但学界对这种理论持广泛的否定态度。更站得住脚也更有趣的是提出这样的问题:为什么在古代社会,制陶技术的进步好像是与其它社会进步平行同步发展的,比如市政机构,包括村庄、城市及法律体系,甚至是更高级更复杂的组织形式,比如帝国。还有为什么这种技术进步不仅仅包括形制上的,比如制造更大或者更轻的陶器的能力,还包括艺术技巧和美学上的提升,而这好像是沿着从几何线条到图形表达的路径发展的?虽然这只是个很简单的例子,却能够说明为什么我作为一个古代地中海文明的研究学者会觉得古代中国如此令人着迷,以及为什么我会有兴趣把我教的课程带到中国来,阐释为什么古希腊被认为是西方文明的“起源”。

通过我执教的课程的简介和我今天的发言,您可能注意到了我对事物起点的浓厚兴趣,所以我希望在结尾时关注于昆山杜克大学的这个方面。我最近读了一些论述,关于道路体系和关于路途的比喻如何影响了中国古典时期的意识形态和思想。所有的旅途,无论是真实的还是比喻的,都当然会有一个起点,而且在古代中国,通常会在旅途开始的时候举行隆重的仪式并祈福。我碰巧找到一段那个时代关于旅途的祝文,是这样写的:

今岁淑月,日吉时良。爽应孔加,君当迁行。……君既升舆,道路开张。风伯雨师,洒道中央。……苍龙夹毂,白虎扶行。朱雀道引,元武作侣。……长乐无疆。

作为一个研究古希腊的学者,当读到这种乘上马车开启旅途,并有神兽作伴的诗句时,会有另外一首诗跳入我的脑海,是古希腊哲学家和诗人巴门尼德的作品,这首诗几乎可以非常自然的和上面这首中国祝辞衔接。这首诗是这样写的:

乘着骏马,朝着心灵的方向,圣女指引我走上女神的吉祥之路,让思想如星空般广袤。骏马奋蹄,我乘车飞驰……圣女们是太阳神的女儿,护送我前行,将黑夜抛在身后,向着光明的方向。黑夜与白昼交汇之门就在前方……沿着宽阔的吉祥之路,圣女们驱动骏马和车驾呼啸而过穿越大门,和蔼的女神在那里迎接我,牵起我的右手说道:年轻人,乘着圣女们驾驶的马车来到我的面前,欢迎你!让你踏上这条旅途的决非厄运,而是正直和正义,你将因此而得以学习世间万物的奥秘……

一个吉祥的日子,一条吉祥之路,的确如此。我谨代表全体教师,怀着愉悦的心情对你们说:“让我们启程吧!”