This picture, taken on the Brooklyn Bridge on November 17th by Mother Jones reporter Josh Harkinson, is one of thousands of images generated by the Occupy Wall Street movement. The sign is at once a declaration and a question: “Something is Happening.” But what, precisely, is it? And were will it take us?

It’s now just over two months since protestors pitched the first tents at Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan, affectionately dubbed “Liberty Plaza.” I’ve found myself riveted by the daily twists and turns of this story, the way a quirky, playful idea first floated by Adbusters rapidly became an energetic movement. I’ve followed the events largely from afar, the way I follow football: watching it live via ustream channels or on youtube, discussing it on twitter, and talking about it with friends. But there are many people like me out there, I think — interested, sympathetic, active spectators. Indeed, the Occupy movement has blurred the boundaries between observation and participation. Its open, fluid, and leaderless form — often cited as a liability — is turning out to be one of its greatest strengths. It seems to me at least ideally tailored for the times, for a moment when political certainties seem increasingly dubious, and where it’s incredibly difficult to get clarity about what lies ahead for our nation. But the movement has already managed something quite important: it has sent a gentle but potent buzz through the body politic, shifting — ever so slightly — the terms of debate and the forms of political imagination available in the U.S. and beyond.

It’s impossible to know what will happen next: events keep unfolding furiously, day after day. But it might be worth trying to make sense of the unexpected processes at work during the past two months.

The movement found its local expression here at Duke and in Durham. Though Occupy Durham wasn’t able to set up a permanent encampment for more than a few days, protestors hold regular General Assemblies and organize other events on the main plaza in the center of the city. They created an exhibit of short personal narratives by “part of the 99%,” and hung them in the plaza for a few days. At Duke, meanwhile, a small but devoted group of students set up tents right in the center of campus, not far from the university’s iconic chapel. Today the tents came down for Thanksgiving break but the tables and chairs are still there, along with a sign that announces, cutely, “BRB” — Be Right Back. The encampment has the permission of the campus administration. The whole process has been very congenial; the students, for instance, took care not to hold assemblies when there were weddings scheduled in the nearby chapel. It has involved assemblies and a series of noontime discussions with faculty members about issues related to the Occupy movement. To be sure, Duke does have a particular relationship to camping out; each Spring, students create a small tent city where they live for several weeks awaiting tickets to the Duke-UNC game. So it would have been a glaring contradiction not to allow the Occupy protestors to do the same. Still, as Cathy Davidson has recently written in an important piece on universities and the Occupy movement, credit goes to the Duke administration for having taken a much wiser and more ethical course than many other universities in the past weeks, most notably UC Davis and Berkeley, but also Harvard.

There has been plenty of sarcasm and sneering both on and off the campus about this group; “the 1% is occupying itself!” declared one rapidly circulating photo of the encampment. But of course Duke, like any university, is a complex and diverse place, and there are plenty of students who are not particular wealthy (50 percent receive financial aid). What the Occupy movement taps into, in any case, is a broadly sense that things are not going in the right direction, that the opportunities awaiting college graduates will be much narrower than what they once expected. That is why, as one Duke student wrote, Occupy manages to scare some students, just a little bit, even as most ignore or make fun of it. Anxiety about the future — the sense that it is growing dimmer with each day — can gnaw at you. And when individual anxiety finds some kind of public, community expression, it can rapidly become a potent force. That intersection, between individual sufferings and public mobilization, is the key to any social movement.

The rapid spread of the Occupy movement, of its slogans and symbols, has been unexpected. It’s a truism of American politics that any attempt to mobilize people along class lines faces many obstacles. By declaring “We are the 99%,” the Occupy movement tried to skirt that problem, insisting on a radical inclusiveness, and even inviting the 1% along as well. But in the many critical responses to the movement bouncing around in the media and on twitter (“Get a job!” is a favorite refrain, as if the whole movement is the result of the leisure time of lazy unemployed people), you can see how challenging it is to break through established attitudes and codes.

The Occupy movement has nevertheless managed to do so, creating a new space for people to articulate a critique of the social order. The movement has become a magnet for a powerful, diffuse, but widely shared sense of deep unease about the shape of our institutions and their inability to address the pressing concerns of individuals and communities. That the anxiety and anger seems to run so deep is perhaps why the movement has generated so much concern, alarm, and especially in recent weeks, police repression.

For some time now, younger generations of Americans have been labeled cynics, experts at ironic detachment. In the face of the basic observations that have driven the movement — that financial institutions exercise a tremendous amount of control over our society and our destinies while also profiting from a remarkable level of impunity — we’ve come to expect, even embrace, a pragmatic cynicism. That’s the way it is: money talks. The political process is corrupted by money, sure, but there’s nothing we can do about it. The only solution is to work on oneself, create a persona curated especially for success in the world as it is, for success represents a certain kind of escape from the constraints placed on us by the social system. Cynicism and irony in the face of the political process are in many ways reasonable, and indeed now so well anchored in our collective personality as to be almost unexceptional; they are a daily currency of commentary and exchange.

What anchors the Occupy movement, however, is a profound refusal of cynicism. When I stopped by a General Assembly at Occupy Durham a few weeks ago what struck me (and what struck many other early observers of the movement) was the the honesty and commitment to democratic process. It was striking and moving to see a diverse group of extremely diverse people earnestly discussing matters of immediate political concern, sharing fears and hopes with strangers. In a circle, they really listened to each other, for a long time. They did not, in the end, come to much of an agreement. Meetings are frustrating, open-ended, surely annoying at times. And yet there was a palpable excitement at the fact of actively taking part in an open-ended public debate.

The “leaderless” quality of the movement, its devotion to process — exemplified in the “People’s Mic,” hand-signals, and a general disposition to facilitating public expression through costumes, signs, banners, and posters — is its key strength. If the Occupy movement has been a revelation to many it’s partly because of how well it calls attention to a profound absence in our current landscape: the absence of a public sphere that is not tied up either with government or corporate institutions (including the media). And what has been powerful about these events is seeing groups of people essentially with their backs turned to power, facing one another, speaking to one another.

Despite the earnestness, politeness, and often relatively small size of Occupy meetings and encampments, they have faced increasingly strong police action. In some places, the back and forth has been almost farcical: people at Occupy Denver, forced to take down their tents, built an igloo, which was in turn destroyed by the police — inciting a debate about the precise legal status of an igloo in a park. Later, when the mayor demanded the group elect a leader to speak to local officials, they elected a very smart looking border collie.

But the mounting reality is one of mass arrests on a scale we have not seen for quite some time in the U.S. The Tea Party rallies that began in the summer of 2009, for instance, never led to arrests or police intervention — even when protests arrived carrying guns. Going back further to the 2003 massive rallies against the war in Iraq, there were comparatively few arrests. Such rallies, of course, tended to be more conventional political marches, with permits approved in advance, often occupying public space for a delimited time. The Occupy protests, in contrast, have purposefully pushed the boundaries further by actually creating encampments and organizing smaller, mobile actions through the use of social media.

You have to go back to the anti-World Trade Organization protests in Seattle in 1999 to find something that parallels the kind of churning confrontations we are now seeing. Even that, though, was confined to one city, whereas the Occupy movement is thoroughly national. The New York Times recently noted that the total number of arrests during the last two months — over 4500 — has now surpassed the number of arrests carried out by the Iranian government during the 2009 “Green Revolution” protests. Obviously the two situations are radically different: the Iranian protests mobilized a much broader sector of the population and seemed to represented a greater immediate threat to the government. In response, the regime shot people in the streets, executed some prisoners, and tortured many others, and ultimately stifled the movement. The Occupy protests take place in a parliamentary democracy, where free speech is (mostly) protected. They are not directed against a particular government figure, and they are not organized around mass public rallies of the kind we saw in Iran in 2009 and more recently in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere. Instead, they have been focused on occupations of public space, and small, rolling protests. In fact, the numbers involved have been relatively small — even in New York and Oakland — and many of the encampments across the country are quite tiny, involving dozens of protesters or even fewer.

Nevertheless, in recent weeks, police attacks on the protests have been escalating. There has been, it seems to me, an odd disjuncture between the actual challenge posed by the demonstrations and the weight of the police response. That was strikingly clear in Chapel Hill recently, when a group of protestors loosely linked to the Occupy encampment of the cities took over an abandoned building. In order to drive them out, the Chapel Hill police sent in a heavily armed swat team, as shown in this widely circulated photograph.

Such police action against the protests has, consistently during the past two months, catalyzed and oxygenated the movement. It has been crucial in transforming it from a relatively small and potentially marginal movement into something of national proportions.

What explains the often heavy-handed tactics of the police? Local governments have the option of taking a very different approach, as a few have: simply taking the encampments as a minor issue requiring some supervision. Police and city officials can cooperate with individuals in the camps to make sure there is no criminal activity, that areas are kept clean, etc. If this approach had been followed in more places, notably in New York and Oakland, the movement would likely be weaker now than it is, and may even have started to peter out. Camping out in public places, after all, is pretty tiring work. Much of the energy of the encampments was taken up by simply dealing with the daily issues that came up — providing food, negotiating tent space, etc. And as encampments last longer and longer, such issues inevitably get more complicated and probably harder to deal with.

Instead, Bloomberg — after having initially responded relatively kindly to the occupation — ultimately decided to shut it down. The NYPD worked hard to minimize the coverage of their destruction of the encampment in Liberty Plaza — going in in the middle of the night, blocking airspace above the park to prevent images from news helicopters, and even arresting several journalists. They even smashed the computers confiscated from the site, presumably to destroy any information stormed on them. Nevertheless, videos of the raid made it out, and within two days the police and mayor were facing a rolling set of demonstrations throughout the city. Instead of ending the Occupation, the police seem now to have metastasized it, creating a situation that will probably be far more difficult to police than the largely self-governing city in Liberty Plaza was. Many are now concluding that the eviction from the park may ultimately have been a boon, freeing up the movement and spurring it on.

Watching these events unfold, you do wonder to what extent police forces have yet to fully internalize the fact that everyone now has an iPhone, and that every single action they take will be photographed, filmed, and immediately uploaded onto YouTube. Police are used to filming protestors, in some cases for use in trials afterwards. For some time protestors have been filming and photographing police back. Still, there much more documentation of every police move now than there has ever been. If you watch a ustream of some of these protests or attend them yourself, you’ll notice that any time the police arrest someone iPhones pop out from everywhere, creating an instant archive that can be put to use immediately in the broader terrain of symbolic warfare over the meaning of the movement.

This level of instantaneous representational combat is in fact relatively new. The 2009 protests in Iran were the crucial pioneering movement in this regard, using twitter and YouTube to create an alternative narrative. It’s no accident that Liberty Park, before it was destroyed, included a large portrait of Nedjma, the woman whose shooting by Iranian police during the protests was broadcast around the world, becoming a martyr and a symbol.

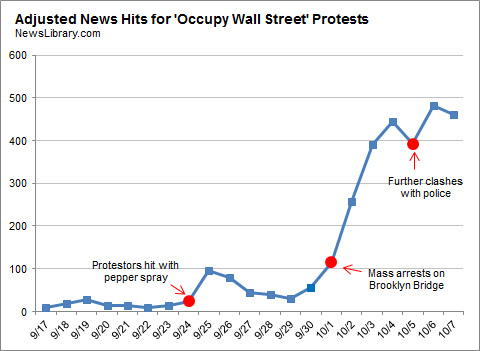

Looking back, it’s clear now how the conscious production and circulation of certain images has been crucial in defining and spread the movement. The process began in earnest with this video, viewed 1.5 million times, of police pepper-spraying two young women. This video brought a sudden spike in media attention to the movement.

It continued with the arrest of 700 protestors on the Brooklyn bridge (including the striking arrest of a child, caught on video)

Nate Silver at 538 offered an analysis of media coverage that makes the point clearly:

Heavy-handed police tactics, of course, might have gotten a certain kind of analysis in the media itself that could have minimized sympathy for the movement. But the proliferation of videos made by participants or observers has played a crucial role here. The mainstream media has almost never reported incidents first. Instead, the media catches up with events after they’ve been circulated on twitter and YouTube, and then comments on them. This also means that social media has allowed protestors to themselves to shape the symbolic terrain of how the movement is interpreted. Nowhere was this clearer than with the uploading and viral circulation of the video of a former Marine Sergeant, Shamar Thomas, dressing down a long line of police officers for using violence against protestors. Now seen almost 2.8 million times on Youtube, it has become an iconic image, twisting and confronting all the usual tropes and story-lines about patriotism, courage, and the place of the military in our society.

Shamar Thomas insisted to police in New York that the U.S. shouldn’t be treated as a war zone, that there was “no honor” in battling unarmed protestors. The video of Thomas, first posted on YouTube on October 16th (in a shorter version than the above), was followed by a video of another veteran, Scott Olson. In the case of Olson, the drama was different: Olsen, who had fought in Iraq and survived, had come home to the U.S. only to be seriously wounded during clashes over the eviction of Occupy Oakland protestors on the night of October 17th. The scene of Olsen’s wounding has been re-edited and circulated in many different videos, but perhaps the most striking is the one below, which has the odd feel of a war movie — as a crowd of protestors rush out of the smoke carrying Scott Olson and crying “We need a Medic! We need a Medic!”

These events helped spur the creation of Occupy Marines, a group of veterans supportive of the movement, as a well as the general strike that shut down the port of Oakland. During that strike another veteran, Kayvan Sabeghi, was beaten up when he stood in front of a line of advancing police, saluting them at one point.

The prominent place of veterans in the such representations of the movement has been crucial symbolically. In the 1960s, returning Vietnam Veterans formed a spine in the anti-war movement. Indeed, veterans groups (led by World War II veterans) organized some very early anti-war marches at the time. The presence of veterans like Olson and Thomas in the movement helps us understand part of what is happened here. We have had more than a decade of war, involving huge mobilizations of young men and women in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soldiers and their families have carried an extremely heavy burden. They have returned to a society where — in part because of massive government deficits caused in significant part by the cost of these wars — many have found difficulties finding stable employment. As was the case after Vietnam, the after-effects of combat are taking their toll, and suicides are vying with the number of combat deaths in ending the lives of soldiers or ex-soldiers. Some veterans have seen the Occupy movement as a forum through which they can express grievances about their experiences, notably about cuts to their benefits and pensions. Because the fact of veteran involvement in the anti-Vietnam war protests often forgotten or actively obfuscated, usually replaced by the image of veterans being harassed by protestors — a process carefully analyzed in Jerry Lembcke’s book The Spitting Image — the presence of veterans in this new protest movement seems to surprise many. But it is in fact part of a long tradition (going back to the radical politics of highly-decorated Marine officer Smedley Darling Butler in the 1930s and the occupation of Washington by the Bonus Marchers) of veterans taking an active and leading role in protests movements in the U.S.

During the first weeks of the Occupy movement there was comparatively little action on college campuses. Recently, though, that has changed dramatically. The events at Berkeley have served as a catalyst for a movement that now seems poised to paralyze the entire UC system. Watching this unfold has been slightly surreal. On a campus whose self-presentation of itself involves much celebration of its days on the vanguard of the political struggles of the 1960s (you can get a coffee at the “Free Speech Cafe,” decorated with pictures of heroic students confronting the administration for the right to protest), police beat up students and a former Poet Laureate and dragged a professor by the hair. You might think the administrators at the UC system might know the history of their institutions well enough to find a way to avoid the blunders of their forebears from the 1960s. At the very least, they might have consulted with any number of their faculty for a quick primer on the way police violence spurs the expansion of student movements. In these cases, again and again, police action against small groups of protesters helped to spur and expand student movements. That happened at Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement, and at Madison in October 1967, where police tear-gassed a small demonstration right as students were going from one class to another. May 68 in Paris was triggered by the entry of police into the Sorbonne. Chancellor Katehi of UC Davis, in fact, witnessed the brutal suppression of a student strike in Athens in 1973, as she pointed out in her apology to the students today — though that wasn’t enough to prevent her from ordering police to take down the student encampment last week.

Though it’s barely been a week since the violence at Berkeley, the cascade of events since then now almost seems inevitable. Protestors at UC Davis set up a camp in solidarity with the Berkeley students. The administration sent in the police to dismantle the camp. What happened next was captured on this video. Already viewed by 1.5 million viewers on Youtube and widely shown in the mainstream media, it became an instant parable.

A remarkable mix of four different videos from the incident provides an event more vivid representation of the strange, almost surreal, set up and action by the police — the long, theatrical shaking of the pepper spray bottle, perhaps in some hope that this would be enough to make the students leave, culminating in the spraying of the students.

As of today, the situation in the UC system seems explosive: during the past years UC campuses have seen a steady set of cuts, and students increasingly have the sense that the educational opportunities meant to provide them with social mobility are being whittled away. As I write, a new, bigger occupation at UC Davis — complete with a Geodesic Dome — is underway. In New York, meanwhile, the campus of the New School is also occupied, and protests directed at potential tuition hikes at CUNY are ongoing. There are, undoubtedly, similar movements stirring on many other campuses throughout the country.

What the Occupy movement has managed to do in the past months is to produce a set of powerful symbols and narratives that both illuminate and challenge the current order. The protestors have, in a sense, drawn out the institutions of power in our society, creating dramas of confrontation that are forcing difficult but crucial questions out into the open. Those who watch the pepper-spraying at UC Davis, or the destruction of the lovingly collected and curated “People’s Library” at Liberty Plaza, are summoned to take a side. The issues the movement is seeking to address — about economic inequality, the corruption of political life, the dismantling of public institutions, the increasingly impossible to bear economic burdens placed on students — have to be tackled head on. So, too, does that fact that so many people feel left out and disenfranchised in our current social order.

The commitment to process and non-violence has been central to defining the movement from the beginning. So has the spirit of humanity, humor, and openness to various perspectives and projects. Maintaining that approach will be crucial if the movement is to continue to have an impact on our public debate.

One of the most powerful illustrations of the the moral possibilities movement took place at UC Davis, documented in the video below. There, the discipline and commitment of the student protestors in the face of the police has shamed the administration. Their dignity in the face of violence makes it clear that something really is happening, and that the future may, finally, be in good hands.

I find that this is fairly representative of the entire movement.

Great article! Would love to read some more!

Excellent article, people are dissatisfied with our political, financial, and educational systems. Unemployment is high, yet wall street gives high bonuses to its executives. The politician in Washington are fighting over payroll tax extensions at a time when most Americans can’t afford to pay another $40 per check in taxes, while the rich are exempt. Schools have to deal with funding cuts by raising tuition fees. That’s the reason why the younger generation feel the need to protest.

Really well written, well thought out post! Here is my only thing…I don’t know how to necessarily conceptualize the term “participant.” By this I mean, people regard their Political participation by joining the “I support the Occupy Wallstreet Movement” Facebook fan page. Whereas, others are actually in the midst of things exercising their Political voice by protesting. Therefore, it is somewhat hard for me to form a definitive opinion as to the extent to which I support the movement.

As you mentioned here:

“During the first weeks of the Occupy movement there was comparatively little action on college campuses. Recently, though, that has changed dramatically.”

..I find that this is fairly representative of the entire movement. Just from the documentation I have tried to follow on the news, the movement seemed to be driven by Politics although the extent to which the movement was occurring was inconsistent through the first two months. I think this needs to be something to be accounted for in general (when talking about the Politics and Economics of the movement as a whole. In general however, Great article! Would love to read some more!

Cheers.

Pingback: What Has Happened? | Possible Futures

Pingback: Sunday Links « Gerry Canavan

Pingback: Sunday Reading « zunguzungu