Given the emphasis on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) in the media and among the finance community, one could easily believe that capital markets are a major contributor to the goal of limiting global warming. We argue this perception is largely false; a narrative strongly pushed by the finance industry to highlight green initiatives and, in so doing, block further (potentially profit-reducing) regulation.

The basic economic idea behind green or sustainable investment assumes that “green” investors derive utility from both the financial gains they earn holding the firms’ shares and from the positive social or environmental impact of these firms. For instance, investors could start buying shares of wind farms, even though they are less profitable than coal-burning energy firms. The wind farms would then experience a (one-off) share price increase, which is associated with lower financing costs, allowing further green investments. Investors happily accept lower financial returns for perceived environmental benefits.

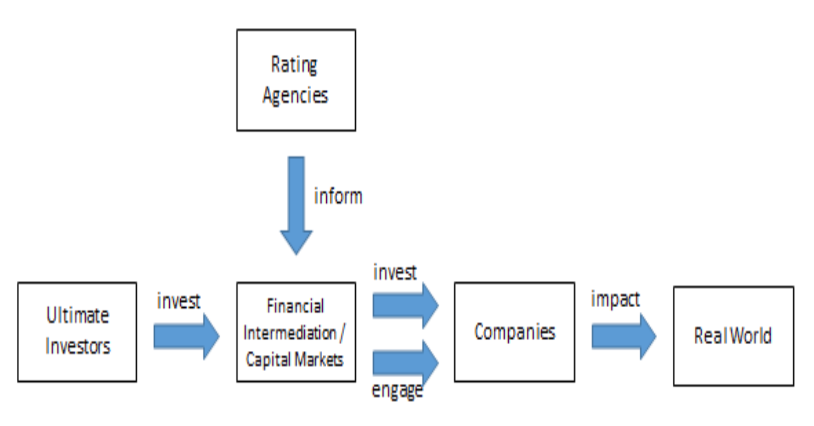

In our recent paper, we analyze the ESG investment process at the micro level: households are the ultimate investors that use some sort of financial intermediaries, such as banks or mutual funds. These, in turn, use ESG ratings either produced inhouse or from rating agencies to inform their investment decisions. They then give loans to firms or buy shares or bonds from firms to deliver (mostly financial) returns to the ultimate investors and to earn their fees. The newly acquired green funding allows firms to change their behavior – e.g., reduce their CO2 footprint– and thus, help mitigate global warming.

Recent research has found, however, that this process is broken in various places as illustrated in the figure below:

Many green investors are less interested in the impact of their investments in terms of CO2 reduction, but more in the good feeling derived from investing in green assets (“warm glow”). Authors from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority have asked, “[h]ow much is the world willing to pay to save the Earth?” and concluded, “[s]adly, not much.” For instance, there is little difference between the returns of green and traditional bonds on average. Green is allowed to hurt a little, but not much in terms of financial returns.

Asset managers love to label their funds “green” or “sustainable” – because this ensures higher demand and higher fees for otherwise near-identical funds. As an insider put it, one firm “reports externally that a large part of the investments are in ESG-compliant investment strategies, but explains internally that it is only a fraction…The sustainability propaganda and rhetoric of [the firm], but also of other financial institutions, got completely out of control.”

Rating agencies are central to the ESG investment process as they are a key source of information for creating investment products and for making investment decisions. However, their ratings of the same firms differ widely, and what they measure is mostly the risk the firms experience from future regulation, not the risk the earth’s climate experiences from further operation of the firms.

Finally, green investments only make a difference to climate change if the investment would not have been done without the green funding: if a new refrigerator is environmentally better than the old one and pays off by saving money due to lower energy consumption, then a firm will buy it regardless of whether the funds used are labeled green or not. This “additionality” is key, as the green funding needs to cause environmentally friendly activity, otherwise nothing changes. Based on close to zero return differences to conventional products, little impact on the “real world” can be expected.

As a result, green finance is more accurately seen as a source of additional fees for the finance industry rather than a means of actual CO2 reduction (or similar good things for the environment). However, few of the people involved seem to care. Investors feel good. ESG rating agencies come into being and flourish. Accountants, commercial and investment banks, asset managers etc. prosper. Companies get (slightly) cheaper funding and a better image. Regulators look busy. Politicians can showcase action and change. And last but not least, business schools are able to offer green investment classes, heart-warming case studies, and a good conscience. Everybody is happy. Only one thing is decidedly unimpressed: the earth’s temperature, which continues to rise.

We should stop waiting for the capital markets to do their magic with “sustainable finance” and instead focus on regulating firms’ actions and emissions directly.

Michael H. Grote is Director of the Frankfurt Institute for Private Equity and M&A at the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

Matthew A. Zook is a University Research Professor at the University of Kentucky

This post is adapted from their paper, “The Role of Capital Markets in Saving the Planet and Changing Capitalism – Just Kidding” available on SSRN.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Global Financial Markets Center or Duke Law.

Very interesting study and position of the two authors, who look at the topic of sustainable investments apart from the general hype a little more critically. I do share the view that anyone who wants to invest their money should take a closer look at companies in terms of sustainability. But I also think it is naïve to expect that sustainable investment alone will change the world. Especially since we still have to consider the issue of “greenwashing” in this context.