Courtesy of Florian Neitzert and Matthias Petras

Sustainability is one of the dominate issues of our time. In particular, public awareness about climate change has recently increased and the associated risks to society have been on the public agenda. On a political level, this culminated in the UN-Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. Since then, movements like “Fridays for Future” and “Scientists for Future” have garnered media attention by demanding a more consequential approach to tackling climate change. The economic transformation necessary to accomplish these groups’ goals present various risks and opportunities for economic decision makers and businesses. On the upside, the increasing demand for eco-friendly products and services provides an economic rationale to adapt to changes in market participants’ behaviour.

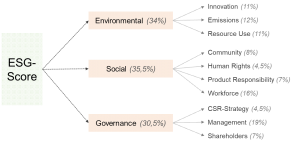

A pressing question remains: How can sustainable products, services, and investments be identified? Currently, there is no commonly adapted identification system. Therefore, the EU is committed to developing a taxonomy in order to provide guidance on the multitude of sustainability seals and labels. From an analyst’s and investor’s perspective, the so-called Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG)-scores provide a broadly used measure for evaluating the sustainability of firms.

ESG follows a broad definition of sustainability. By evaluating the environmental, social, and governance performance of entire firms or specific investments, ESG-scores are more than just indicators of the ecological profile of a firm. They should rather be interpreted as a multiple dimension indicator for corporate social responsibility. The term “corporate social responsibility (CSR)” may therefore be used synonymously with a firm’s ESG-performance, i.e., the consideration of environmental, social, and governance aspects in business decisions. ESG-scores are a measure of the quality of these efforts. Standardized ESG-scores are provided by Thomson Reuters or MSCI.

Importance of CSR for banks

Usually, banks provide capital to firms with both high and low ESG-performance. Recently, so-called “sustainable banks” have become popular, providing services exclusively to projects with high ESG-scores. In general, banks are well-advised to provide sustainable investment opportunities in order to cover the growing demand for such investments. At the same time, banks are predestined to finance the intended ecological transformation of the economy, particularly in bank-based economies. According to the EU Commission’s Action Plan, Financing Sustainable Growth, banks play a key role in transforming the economy into a resource-efficient circular economy. Financial actors can promote integrative growth by allocating capital to sustainable investment projects.

To accelerate the transition towards a resource-efficient circular economy, additional incentives are currently discussed at the political stage. A top priority on this agenda is a bank regulatory privilege for “green” investment projects (green supporting factor), inspired by the supporting factor for small and medium-sized enterprises. However, regulatory incentives only make sense if such investment projects are less risky and increase financial stability.

Aside from their general relevance for society, climate risks are particularly relevant to the banking sector. Risks due to climate change can materialize as additional credit risk, market risk, and reputation risk. Moreover, early adoption to meet expected future regulation can eliminate the need for late and costly adjustments. However, it remains unclear how sustainability and ecological performance relates to default risk and portfolio risk.

Improved governance performance may also reduce bank risk. It is reasonable to assume that better governance reduces operational risks. Moreover, socially conscious efforts may prevent reputational damage.

Research approach

Our study provides empirical evidence on the effects of ESG-performance on bank risk. While extant literature includes several studies on the relationship between ESG-performance and banks’ financial performance, little evidence exists concerning the effects on bank risk. Our contribution is twofold: first, we provide empirical evidence on the relationship between ESG-performance and bank risk. As measures of idiosyncratic bank risk, we use default risk and portfolio risk. Second, we perform an exploratory in-depth analysis of the underlying drivers of the impact of the ESG-score on bank risk. In particular, we differentiate the three pillars of the total ESG-score and study their impact drivers on a detailed sub-component level.

Our data comprises 3,392 banks from 121 countries, covering the period from 2002 to 2018. We retrieve bank fundamental data and ESG-performance data from Thomson Reuters’ Eikon. In order to study the effects of ESG-performance on bank risk, we apply multivariate regression models with controls for bank specific and macroeconomic factors. We analyze the effect of CSR on both default risk and portfolio risk. Specifically, we use the z-score as a proxy for default risk and risk density to measure portfolio risk. In order to explore the drivers of the effect of ESG-performance on bank risk in detail, we differentiate the three pillars of the ESG-score and consider the individual effects of the ten sub-components as well. Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown of the ESG-score.

ESG-performance mitigates bank risk

Our first hypothesis is that the overall ESG-score indicating the banks’ total ESG-performance reduces idiosyncratic bank risk. Extant literature provides empirical evidence for non-financial companies. We confirm empirically that this negative relationship also holds for banks. Both default risk and portfolio risk decrease with statistical significance.

Our second hypothesis builds on the decomposition of the ESG-score into its three pillars. We hypothesize that each dimension on its own should have a risk reducing effect as well. However, we find an ambiguous picture. We find significant and negative coefficients for the environmental pillar. The environmental performance reduces default risk and portfolio risk in our sample. The environmental pillar consists of three sub-components. Looking at these pillars in detail, we find that all of the subcomponents (i.e., Environmental Innovation, Emissions, and Resource Use) support and drive this effect. Building on risk management theory, we argue that investing in next generation green technologies is less risky in the following years than investing in less promising business models. This argument is particularly relevant if investments are made in state-sponsored new technologies. Because of more stable income streams, lower balance sheet risk is also associated with lower default risk. Additionally, reputation theory can explain higher and less volatile income streams and therefore lower default risk. Environmental engagement is predestined to improve the reputation and add to a green, young, and innovative image of the bank.

Figure 1: Breakdown of the ESG-score by Thomson Reuters

The social and the governance performance of the bank show a default risk reducing effect, but no significant effect on portfolio risk. These results can be explained by reputation theory and stakeholder theory. Additional efforts for good governance signal a stable and considerate risk management. As a consequence, earnings are stabilized. Social efforts have the potential to improve the image and reputation of the bank. Banks with a better reputation may even have higher earnings. Both reduce the probability of default. The picture of the sub-components is again ambiguous. Within the governance pillar, we identify that the Management score affects default risk negatively and significantly. The CSR-Strategy contributes to both a reduction of the default risk and the bank’s portfolio risk. Considering the social pillar, we identify Human Rights and Product Responsibility as risk reducing factors for both risk measures. For the Workforce score, we observe a risk reducing effect on default risk.

Our third hypothesis investigates the impact of controversies on bank risk and assumes that controversies increase idiosyncratic bank risk. Controversies may be lawsuits, management departures, or allegations of social and ethical misbehavior. Reputation theory suggests that those banks which care about their reputation do their business more carefully and have less risky asset portfolios. Our results provide empirical evidence that controversies increase default risk and portfolio risk. In line with reputation theory, the risk density is lower for less controversial banks. We explain the higher default risk of controversial banks by their lower earnings in the years following the controversial events and more volatile earnings in general.

Implications

Our study shows thatthe ESG-performance of a bank has a mitigating effect on risk. Therefore, we provide additional rationale to engage in ESG-enhancing activities. Our results might serve as encouragement for banks to engage in ESG-activity, in addition to the already growing customer-demand for ESG-investments and obvious regulatory trends in favor of engagement in projects with a strong ESG-profile. However, regulators are always well-advised not to use the capital regulation framework as a political instrument to foster investment in these sectors. Despite the evidence provided in our study, it remains unclear whether an additional increase in ESG-performance leads to a further mitigation of bank risk. It is possible that an additional increase in ESG-activity yields a decreasing marginal benefit or, at some point, even a decreasing effect. If this is true, a green supporting factor would lead to perverse risk-taking incentives at the cost of idiosyncratic bank stability.

Very interesting article.

Very interesting article.