Thanks to a generous gift from the Lauder Family Foundation and the support of the Center for Jewish Studies, the whole class went on a trip to Italy over spring break. During our time in Italy we built on our historical knowledge, reflected on how seeing sites in person changed our interpretations of the we have read, and considered what new questions our visits raised for the next part of the course, which will be guided by students’ individual research projects. While a range of courses would benefit from the addition of a travel component, Jewish Italian literature and history are especially rich and complex topics that have garnered increasing scholarly and popular attention. In large part because of this trip, students have found precise research topics that will contribute to current discussions about the significance of Jewish Italy and its literatures.

Below are the students’ trip blogs, also linked by their names. While a few of them share that we were not always lucky with weather (and in Venice had to readjust our plans due to acqua alta), we were very lucky with our guides.

I am grateful to these guides, the Lauder Family Foundation, the Center for Jewish Studies — especially Serena Bazemore and Professor Laura Lieber, Professor Martin Eisner – the other professor helping to lead the trip, and the wonderful Duke students of the class for ensuring that the experience was educational, fun, and unforgettable. The students’ blogs reveal how their personalities and interests helped shape our understanding of Jewish Italy.

March 10th: Arrival: Moses & San Clemente by Madison Cook.

March 11th: The Roman ghetto with Yael Calò by Tiffany de Guzman.

Catacombe ebraiche di Vigna Randanini with Yael Calò and Sara Terracina by Naveen Hrishikesh.

March 12th: Ancient Rome with Marco Misano by Melissa Gerdts.

Vatican with Marco Misano by Julia Ryskamp.

March 13th: Ostia Antica with Elena Andreoli by Maegan Stanley.

Protestant/Non-Catholic Cemetery, tour with Nicholas Stanley-Price by Uriel Salazar.

March 14th: Ghimel for lunch and Jewish Venice Tour with Luisella Romeo by Maryam Asenuga

March 15th: Trieste (Jewish Museum, Svevo & Joyce Museums with Riccardo Cepach, Antico Caffè San Marco, Synagogue with guide) by Natalie Ekanow and Daniel Rubinstein.

March 16th: Four Synagogues & Jewish Museum in Venice by Jason Beck.

Scavenger Hunt & View from Fondaco dei Tedeschi

March 17th: The Guggenheim

We Are Finally Here: Day 1 in Italy! by Madison Cook

After an extended delay in JFK and nine hours in the air, the Italian Judaism seminar finally arrived in Rome! Our bodies may have been jet-lagged, but the excitement of Italy kept our energy high.

The experiential learning began immediately. We separated into cabs that we immediately noticed were quite warm and Tiffany promptly reminded us that Italians are afraid of the cold. We left our stuff at our hotel Casa de’ Fiori and quickly headed to our first Italian meal at Ditirambo.

Our dining experience at Ditirambo was a great way to start off our trip. Our appetizers were authentic Italian dishes unlike anything I’d ever had before. We had panzanella, lots of burrata, eggplant meatballs, and so many incredible pasta dishes. We finished the meal with our first shots of Italian espresso! And then, we were off on our first afternoon of touring.

Our first stop was Michelangelo’s Moses statue in San Pietro in Vincoli. The statue marks Pope Julius II’s tomb and the horns on Moses’ head represent the statue’s connection to the words of Exodus (of the Catholic bible, though the horns are a result of a mistranslation). We discussed the irony that exists within the history of this piece: Jews worshipped the statue (even though idols are outlawed in the Torah) AND the statue rose Michelangelo to divine status (rather than Moses or Pope Julius) because it such an incredible structure.

Next, we went to San Clemente and explored the history of Rome through the lens of this layered architecture. The first layer represents fourth century Roman society, the second layer represents fourth to eleventh century society, and the top layer is the most recent portion of the Basillica. Notably, on the first floor is the first written Italian words in history. I found the written words and layered structure to be a really interesting and informative introduction to Rome. The layers are a staple of Roman architecture and the vernacular illustrates the important historical role that Rome has in the development of Italy. Overall, this visit helped me understand just how fast Roman history really is.

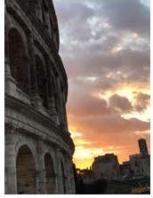

Finally, we ended our day with a beautiful sighting of the Coliseum during sun

set. This was the perfect way to finish off an amazing first day! It truly was a surreal moment. After arriving in Italy only a couple hours before, I got see one of the most historical sites in the world!

Overall, I loved the city of Rome. It’s unique in that, despite having the “hustle andbustle” of a large city, it has arguably more history, personality, and ultimately beauty than anywhere else.

Personally, the most important thing I learned on our first day was simply the meaning of being an international traveler. This was my first time traveling to Europe and the experience of finally seeing that side of the world was surreal. I recognized the importance of fully immersing in the culture and challenging myself to learn as much as I can wherever we went. Because at the end of the day, this trip was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

My first day of experiences made me feel more connected to Elsa Morante’s La Storia. I felt more connected to the scenes and experiences she described; her words took on a new meaning for me.

Jewish Italy: The One Where We Crash a 25th Anniversary Ceremony by Tiffany de Guzman

We began our first full day in Rome with a tour of the Jewish ghetto. Our tour guide was Yael, a magnificent woman and proud Roman Jew (one of 13,000 in Rome today). To begin our tour, Yael described the physical space of the Jewish ghetto in Rome and how it has changed from its creation in 1555 to today. When the ghetto was established by Pope Paul IV in July of 1555, it consisted of only two streets and four blocks and was gated at night. This cramped area forced the buildings in the ghetto to be built much higher (often seven to eight floors) than the buildings in the rest of Rome—only worsening the already terrible living conditions by blocking out the sunlight. Outside of every gate was a Christian church, likely displaying a sign written in Hebrew in an effort to convince the Jewish community to convert to Christianity. The Jewish ghetto continued to be enforced by every following pope, officially ending in 1870, when Rome joined the recently united Kingdom of Italy.

An example of how high the buildings in the Ghetto could be.

As we walked through the streets, Yael made various stops to point out important areas, doors, and plaques remembering the deportation of over 2,000 Jews from Rome in October of 1943. In September of 1943, the Nazis had given the Jewish community 36 hours to pay over 50 kilograms of gold to remain in Rome. They actually managed to collect the gold, but their efforts did nothing more than create a false sense of security within the community. As Nazis took the Jews from their homes, they furthered this false security by instructing them to lock their doors and bring their keys with them. This order made it less likely that they would run, since it seemed as if they would be returning home in the near future. These written orders, along with the receipts issued to those who contributed to the 50 kilograms of gold, can be found in the Jewish Museum in Rome.

Receipts issued to the members of the Jewish community that contributed to the 50 kilograms of gold, in hopes of avoiding deportation.

The instructions given to Jewish people as they were being deported, fostering a false sense of security.

Objects commemorating the lives lost can be found not only in the Jewish Museum, but also scattered throughout the rest of the city. It was during this tour that we were first introduced to the stolperteine (stumbling stones) that are located all throughout Europe. These “stones” are Rome’s smallest, but incredibly meaningful, monuments to remember the victims of the Holocaust. They are small golden squares nestled into the cobblestones and are normally located in front of the individual’s residence, but are also occasionally found in front of their workplace. The stones give the person’s name, birth year, the day they were deported, the camp they were deported to (often Auschwitz), and the date of their death. Gunter Demning, the artist behind the stolpersteine, sought to give a name back to the Holocaust victims that are too often reduced to a mere number. As our trip went on, we continued to point out the small stones throughout Rome, Venice, and Trieste.

Stolpersteine outside of an apartment building in the Jewish Ghetto.

Our first day was also full of learning about the history of Rome’s synagogues. During the period of the Ghetto, nearly all of the synagogues were closed down (another effort by the Papal state to convert Rome’s Jews). However, the synagogue known as the Cinque Scole managed to survive. This synagogue got its name from the fact that while it was only one building, it was home to five different “schools” of Jewish practices, such as the Scola Nuova and the Scola Siciliana. Yael showed us around the part of the museum with treasures from the Cinque Scole, taking time to point out the ornate Torah crowns (keter) and precious fabrics for covering the Torah. Jews weren’t allowed to own property, so they used their money to donate elaborate objects to their synagogues, often as a status symbol or a way to remember deceased family members.

A few of the Torah crowns and covers in the Jewish Museum.

We ended our tour of the Jewish Ghetto with Yael by visiting the Tempio Maggiore, or Great Synagogue. The synagogue is certainly deserving of its name; it’s the largest of all of the synagogues in Rome today and stands out in the city through its eclectic style and square dome (the only one in the city). Once one enters inside, it is impossible to not be blown away by its breathtaking beauty. Additionally, if you’re as lucky (and willing) as we were, you may be able to crash a 25th Anniversary ceremony in this beautiful space! The synagogue was built from 1901-1904, after the destruction of the Cinque Scole in 1893. The construction was funded by the members of the Jewish community and today, it still overlooks the old Jewish Ghetto. The Great Synagogue serves both as a remembrance of centuries of oppression and confinement and a celebration of their freedom.

Il Tempio Maggiore (The Great Synagogue) from the outside.

Inside of the Great Synagogue.

The Great Synagogue sits on the eastern bank of the Tiber river and as we walked along its edge, I couldn’t help getting lost in my thoughts. The Tiber river suddenly represented so much all at once. It was no longer solely the river that flows under the beautiful Ponte Sant’Angelo, one of my favorite spots in Rome in the late evening (once most of the tourists have dissipated). It was no longer a seemingly fictional setting where Useppe and Bella went to play and dream in La Storia. Now, after our tour, it was impossible to see it without remembering its purpose as a natural gate and enemy for the population of Rome’s Jewish Ghetto. I found that this intermingling and clashing of roles and identities continued to resurface throughout our trip, whether it was in terms of the characters from our readings or the dark history of an often overly-romanticized Italy.

Crickets, Darkness and Tombs, Oh My: Exploration of The Jewish Catacombs by Naveen Hrishikesh

After a morning in the Jewish Ghetto of Rome, we made our way to the Jewish Catacombs. Here, we would be reunited with our guide from the morning, Yael and another tour guide. My taxi was the first to arrive and immediately we were taken by the spooky nature of the Catacombs. It almost seemed as if we were in the wrong place because there was no one else in sight. The caretaker arrived soon thereafter, a cantankerous man named Alberto who refused to tell us his last name. His presence fit with the ominous nature of the Catacombs. Eventually, the entire group arrived and Alberto gave us a waiver to sign along with some flashlights to guide the way once we were inside. Yael had warned us about the complete darkness and the presence of jumping crickets. A large number of us were frightened to say the least. Thus, we were divided into two groups and mine was the first to enter.

https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg ” data-medium-file=”https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg?w=300″ data-large-file=”https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg?w=584″>

https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg ” data-medium-file=”https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg?w=300″ data-large-file=”https://saskiaelizabethziolkowski.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/dscn03981.jpg?w=584″>

The ominous entrance to the catacombs.

Once inside, we learned a lot about the purpose and history of the Jewish catacombs. We were being treated to a very special tour of something that most people are not allowed to see. The catacombs are the most obvious evidence of Jewish presence in Rome. Jewish people were buried in shelves. It was not kosher to put the bodies in coffins, so the proper way to bury the dead was to place them in these shelves and covered with dirt and mud. This made it easy for bodies to resurface as the covering would disintegrate, meaning they were constantly reburied to remain hidden.

One of the burial shelves, where body parts have resurfaced. This is not uncommon to find in the catacombs.

In the catacombs, there were many rooms on either side of the infrastructure. These signified whole families who were buried together. In these rooms, there were inscriptions in Greek that signified the family name and who was buried where. Along with these inscriptions were elements of Jewishness, including Menorahs drawn around the room. The presence of the color red was also prevalent, chosen to make the tombs very particular.

The presence of the menorah can be found throughout the rooms in the catacombs, displayed in the prevalent red coloring.

One of the many plaques with Greek inscription signifying information about who was buried where.

The dimensions of a tomb changed based on whether a person was big or small. While in the catacombs, we saw a tomb of a baby who had passed away. It wasn’t uncommon for children to die young and be buried. Yael informed us that a larger room dedicated to one family signified a wealthier family, who was connected to Roman society in some way. Towards the end, we saw a room that had once been adorned in Pagan icons and idols but was reclaimed and used as a Jewish tomb for a wealthy family.

The pagan adornments of the large tomb. The Jewish family reclaimed this space and made it their burial room.

Further into the catacombs, we examined a Coquim, which was a tomb that was perpendicular to the wall. This signified a more “Oriental” way of burying people. Multiple people would be buried in this style of tomb. Near this tomb, we saw the skull from a body where the covering had again disintegrated.

The body parts of a Jewish person whose body had become uncovered. If you look closely, you can see the top of a skull.

Along the way, we were greeted by black crickets that had the ability to jump. They looked like spiders from far away, but they only had six legs. We were all terrified by the creatures and more than once, hustled our way through the narrow halls of the catacombs. It was a fright to say the least. As we neared the end of the catacombs, we noticed how many of the stone inscriptions featured various images. Yael told us that these signified the jobs that each member did when they were alive. For example, one featured a cow, telling us the person was a butcher in their life.

The image of the cow signified the job that the person buried here did when they were alive.

In order to exit the catacomb, we had to travel the same path backwards. There was only one entrance and exit. Once we reached the entrance again, the caretaker stopped to show us a well in one of the rooms at the front of the catacomb. It was used to hide bones. Many would use it to search for jewelry and valuable items. However, this proved to be fruitless as Jewish people were not buried with material things of value.

The well that was used to sift through bones for valuable items. The well is now covered, as you can see in the picture.

My group exited the catacombs about 30 minutes before the second group, so we waited outside as it rained. This only added to the mysterious atmosphere of the catacombs. After everyone was out, we took a group photo to remember this unique experience. It was definitely something that I never would do alone, but with a group, it was quite an adventure. We said our goodbyes to Alberto and the catacombs in the pouring rain and waited for our taxis to take us back to the light of our hotel.

Our group, glad to be out of the darkness and away from the crickets but not disregarding this unique experience.

The Jews and the Colosseum : An Ancient Minority in Ancient Rome by Melissa Gerdts

When you think of Rome, the first thing that probably comes to your mind is the grand Roman empire, ruthless conquerors and warring gladiators. The Roman Colosseum is the most influential, representative, and important symbol of this era. Formally called the Flavian Amphitheater, it was commissioned in 72 CE by Emperor Vespasian of the Flavian dynasty. After only eight years of construction, it was officially opened by Vespasian’s son Titus in 80 CE.

Our very energetic tour guide Marco Misano told us that one theory behind the popular name of Colosseo was a reference to the colossal gilded bronze statue of Nero which stood outside the amphitheater until the 4th century CE. For some reason, the name stuck.

Just outside the Colosseum, where the statue used to stand, is the Arch of Constantine. It was built in 315 CE to mark the victory of Constantine over Maxentius at Pons Milvius.

The Colosseum was a freestanding structure made of stone and concrete, with grandiose marble seating and decorations. It was built with the plunder of the conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE and primarily built by the Jewish slaves brought back from Jerusalem.

Inscription that states that the money used to build the Colosseum came from the conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE

In total, there are around 80 arch entrances and enough room for 55,000 spectators – very similar to the large sport stadiums of today. The architectural style is unique in the sense that each floor had a different column type—the first floor had Doric columns, the second Ionic and the third level Corinthian. Standing at 150 feet with four stories and a width of 615 x 510 feet, this colossal structure dominated the city.

The Colosseum held spectacular gladiator fights to the death, wild animal hunts including lions and bears, and public executions. They also used to hold recreations of large naval battles by flooding the arena but these were not as popular due to the lack of gore and blood the spectators wished to view.

So who exactly were the gladiators? The gladiators were primarily slaves, prisoners of war, condemned criminals and mentally unstable Roman citizens. The winners would earn a large sum of money which they could use to buy their freedom and escape the games. However, some people liked the glory that fighting in the Colosseum brought them and chose to remain in the games.

In 404 CE, with the changing times and tastes, the games of the Colosseum were finally abolished by Emperor Honorius. The Colosseum was largely abandoned after this and then an earthquake in 1231 caused the southwest façade of the Colosseum to fall apart. The top part crumbled and the outer ring of part of it is completely gone. Because this side was constantly exposed to the sun, it made it more susceptible to damage. Fortunately, the rest of the Colosseum still stands.

Fun Fact: In 1749, Pope Benedict XIV actually consecrated the Colosseum in memory of the Christian martyrs who had lost their lives there. But this claim has no real proof and its validity is still largely disputed.

Marco also showed us a Roman coin which had an image of a strong gladiator figure juxtaposed with a poor beggar Jewish woman. This was meant to symbolize the victorious Titus and a personification of Judea. How interesting that not only did they use the Jews’ own treasure from Jerusalem to build the Colosseum, used Jewish manpower but also that the coins of the time reflected Roman victory and Jewish inferiority.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a picture at the top of the Colosseum because it was pouring rain and the violent wind made for unsavory pictures…

After we left the Colosseum, however, the weather decided to stop hounding us and the sky opened up to be a beautiful day.

We proceeded to walk through the Roman forum where we were able to see images of how the forum used to look like (thanks to Marcus’ picture book!) and then see how far the buildings have deteriorated in the present day. Its destruction was primarily due to natural disasters as a lot of earthquakes have plagued the city of Rome and also because the church took the marble from the ancient temples to build St. Peter’s Basilica and other religious buildings.

Fortunately, the entrance to the forum –The Arch of Titus—is in pretty good condition save some graffiti on the inside of the arch. This arch is a Roman triumphal arch which was erected by Domitian in 81 CE at the top of Via Sacra (meaning “Sacred Way”) in the Roman Forum. It commemorates the victories of his father Vespasian and brother Titus when the great city of Jerusalem was sacked and plundered in 70 CE. One panel has an image of a menorah, some trumpets, and what seems to be the Ark of the Covenant carried by Roman soldiers. The Jews actually refused to walk under the arch because according to old Roman law, once you did you were no longer considered a Jew. Crazily enough, this ban was only lifted until 1997.

The Jewish Vatican by Julia Ryskamp

After a busy morning spent visiting the Colosseum and Forum—Rome’s most famous ancient sites—during the second half of our Monday in Rome we reunited with our guide Marco to tour one of Catholicism’s most important sites—the Vatican. We received our first sight of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica crossing the Ponte Sant’Angelo, and even from a distance it was hard not to be in awe of the beauty and splendor awaiting us in the Vatican. Although the smallest country in the world, with an area of 0.17 square miles and a population of about 1000, the Vatican City is nonetheless home to some of the most important religious and cultural sites in the world: St. Peter’s Basilica, the Vatican Museums, and, of course, the Sistine Chapel. Despite its size, the Vatican City holds immense power: the Pope is the only absolute monarch in Europe and the country is the seat of the Catholic Church (the largest Christian denomination in the world, with nearly 1.5 billion members).

A view of St. Peter’s dome from the Ponte Sant’Angelo

Walking through the streets of Vatican City, it seemed as if every tourist in Rome had decided to visit at the same time as us; the long lines wrapping around the walls of the City and the masses of people in the Museums and Basilica, and gazing up at the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, were truly a testament to the extreme cultural, historical, and artistic value of the Vatican’s treasures, as well as a reminder of the importance of the Vatican for so many Christians who visit from all over the world.

Our tour of the Vatican began in the Vatican Museums, which contain one of the largest art collections in the world, spanning over 9 miles. While we only saw a small portion of the collection, walking through the Tapestry and Map Rooms, what we did see offered us a glimpse into the extraordinary richness and splendor of the treasures of the Vatican. Before entering the Sistine Chapel, Marco explained to us the history behind the four years it took Michelangelo to paint the chapel. Commissioned of him by Pope Julius II, Michelangelo thought the task was nearly impossible, and resented the pope’s treatment of him. However, unknown to most people both in the sixteenth century and today, Michelangelo painted secret messages in the Sistine Chapel condemning the corrupt Pope and secret symbols that advocate for a reconciliation between Christianity and Judaism.

At first, the idea of secret signs and messages in the paintings sounded like something out of The Da Vinci Code. However, with the help of our guide we could see these hidden symbols and messages with our very own eyes. Most significantly, Michelangelo painted only scenes from the Old Testament. He did this on purpose; at a time when the Pope was afraid that people would read the Old Testament and want to convert to Judaism, Michelangelo wanted Jews and Christians, and the Old and New Testament, to be connected. Looking closer at the individual paintings, you can see that Jesus is painted with all five fingers showing (representing the Five Books of Moses) rather than only three (which would represent the Holy Trinity); the side of the Chapel depicting the story of Moses is painted from right to left, like Hebrew; two Jewish figures (distinguishable by their yellow and pointed hats) make up the central group of figures surrounding Christ in The Last Judgment, indicating their place in Paradise; and, also, in the panel depicting the Fall of Adam and Eve, the forbidden fruit is depicted as a fig, in the Jewish tradition, rather than as an apple. Furthermore, The Sistine Chapel itself was designed to match the proportions of Solomon’s Temple as described in the Old Testament.

A furtively taken picture of the Sistine Chapel ceiling

The Last Judgment can be seen on the back altar wall

Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel between 1508 and 1512, forty years before the establishment of the Roman Jewish Ghetto in 1555. His hope for reconciliation between Christians and Jews went unfulfilled in his lifetime, and for a long while afterwards. During World War II, Pope Pius XII remained outwardly silent amidst the Nazi’s genocidal agenda and the deportation of thousands of Jews from Rome and around Italy. It was not until 1960 when the Vatican, led by Pope John XXIII, finally declared that the Romans, and not the Jews, were the ones that killed Christ. Both of these facts are stark reminders of the long and complex history of the (mis)treatment of the Jews by the Catholic Church.

Our tour of the Vatican ended inside the breathtaking St. Peter’s Basilica, where we saw Michelangelo’s stunningly beautiful Pietà and the massive dome of the Basilica, also designed by Michelangelo, the tallest in the world. Even in here could be found a connection to Judaism: the columns of the central altar of the Basilica were in fact modeled on the ones in the Temple of Jerusalem. Outside, we watched the changing of the Swiss Guards in front of the Basilica and took pictures in St. Peter’s Square, including a cheesy, but cute, one of us standing in the two countries—Italy and Vatican City—at once. As the sun began to set, we headed out to round off our day with the Pantheon, dinner, and gelato.

Michelangelo’s Pietà

Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica

The altar in St. Peter’s Basilica, with columns modeled after those in the Temple of Jerusalem

After our day at the Vatican, I reflected not only on the significance of the art masterpieces I had just seen, but also on the unique nature of the Vatican’s connection to Judaism. With so many people traveling to visit the Vatican each day, and as the head of the largest Christian denomination in the world, the Vatican and the Pope have an immense responsibility to not only preserve the beautiful art found in the country, but to also represent truthfully to all visitors the complex and deep connection between Christianity and Judaism that is undeniably a part of the Vatican’s history. In these responsibilities also lies a duty to guide the followers of Catholicism toward tolerance and acceptance of other faiths and belief systems. Our Jewish tour of the Vatican was an incredibly powerful attestation of the connectedness of the Jewish and Christian religions, as well as a monumental reminder of the importance of the continuance of the reconciliation between the people of these two religions.

Group picture in St. Peter’s Square

Ostia Antica & its Synagogue by Maegan Stanley

The ruins of the earliest Jewish synagogue in the Western world, at Ostia Antica

On March 13th, we spent the first half of the day visiting the archaeological site of Ostia Antica, which was once the seaport city of Rome. Although Ostia’s history as a settlement stretches back to the 4th and 3rd century B.C.E., the majority of buildings visible at the site today date from the 1st and 2nd century C.E. As we walked down the city’s main street, called the decuman, we passed the ruins of tombs, shrines, storehouses, flour mills, apartments, homes, public baths, a cafeteria, and a Roman theater. Ostia Antica’s ancient population of 15,000 was known to have historically been very multi-ethnic due to the nature of Roman trade, but it was not until 1961 that archaeologists began to excavate Europe’s very first synagogue in an extreme corner of the ancient site.

A view over Ostia Antica’s main decuman, showing the bath houses of Hadrian

The synagogue’s plan is rectangular in shape, with dimensions of 75 feet by 37 feet. It was built from volcanic tuff, like the majority of Ostia Antica, and likely included a second floor to seat women during religious services. A marble well was positioned near the synagogue entrance for ritual washing, and marble columns decorated with iconography of the menorah framed the shrine that once housed the Torah.

Marble column with visible menorah iconography on the lintel

The marble well-head at the entrance of the synagogue

An oven can be found inside the synagogue, for the baking of unleavened bread. An inscription in Latin on the synagogue’s floor marks the space as an acceptable site for Jewish burials. What was most surprising to me about the Ostia Antica site as a whole were the remarkably well-preserved mosaic floors. One particularly noteworthy mosaic in the synagogue depicts four interconnected loops in an ancient symbol representing infinity and the circle of life.

Symbol of infinity found in the ancient floor mosaics of the synagogue

The Jewish synagogue of Ostia Antica speaks to the cosmopolitan nature of ancient Imperial Rome, and its relative tolerance for the Jewish population that came to populate the port as trade increased under Claudius. It solidifies the importance of the Jewish community to the trading economy of Rome, and presents the earliest evidence of a Jewish-Italian identity on the Italian peninsula. However the archaeological site does raise a question. Is there anything to be inferred about the relationship between Ostia Antica and its resident Jews from the physical distance between the heart of Ostia Antica and the synagogue?

Not just a cute picture of us, but also a demonstration of the distance between Ostia Antica and the location of the synagogue

From Testaccio to Trastevere, and Beyond! by Uriel Salazar

The second half of March 13th started after lunch at Da Bucatino, on via Luca Della Robbia. Specifically, this homely restaurant is in Rome’s Testaccio Quarter, famous for its artificial mountain made from amphorae, special jugs used as vessels for transport in the port that was located on the other side of Porta San Paolo. It was in this popular quarter that Elsa Morante lived for part of her life, and where Ida Ramundo and Useppe lived during the second half of La Storia.

In 1944, after the German Occupation of Rome, Ida moves from her stuffy refuge in Pietralata to Testaccio. Part of her stay in Testaccio is with the Marrocco Family on Via Matro Giorgio, where she rents a room from a family waiting for their men to return from the war. Eventually, in 1946, Ida finds her own apartment on via Bodoni, which actually intersects via Luca Della Robbia. In Testaccio, Ida is close to where she teaches classes, and is able to leace Useppe at home with Bella, under the surveillance of the concierge’s niece, Lena-Lena.

During a scene in the book, Ida walks to the ghetto in a stupor, while confronting very strong feelings of anxiety as she walks through the empty houses that belonged to the Jews of Rome, alongside the horrible realization that she may never see any of them again. The distance between her home in Testaccio and the Roman Ghetto in Trastevere is actually somewhat short, and in reality, is not much longer than a fifteen minute walk.

A Google Maps Screenshot demonstrating the short distance between Testaccio and Trastevere.

Not far from Testaccio is the Protestant Cemetery of Rome, easily spotted due to the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, which makes up its southern border. Established in 1716, the cemetery is also known as The Non-Catholic Cemetery for Foreigners in Testaccio. According the the cemetery’s website, it is home to more than 50 nationalities and religions, with tomb inscriptions in over 15 languages. There are three major qualifications for burial in the cemetery- you must be non-Catholic, non-Italian, and a resident of Italy.

The pyramid of Gaius Cestius, along with the Aurelian Walls (added in 217 AD), that make the southern boundary of the cemetary. The cemetery is now considered a national cultural zone in Italy.

Our tour guide was Nicholas Stanley-Price, author of The Non-Catholic Cementery in Rome: Its History, People, and Its Survival for 300 Years, who noted not only the age and continuous use of the cementery, but also how it contains a high number of famous and important graves, such as John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Edward Trelawny, Antonio Gramsci, and many others. The cemetery has seen multiple threats to its continuous use by almost becoming a portion of the city during the industrial revolution and again through Mussolini wanting to replace it with roads, much like with Circus Maximus.

The cemetery itself was founded due to how laws of the Catholic Church prevented the burial of Protestants (and anyone non-Catholic) in Catholic Churches and consecrated ground. However, due to the amount of foreigners throughout Italian history, many non-Catholic cemeteries began to appear. Specifically, Pope Clement XI granted a group of exiled protestants from the Stuart Court to be buried in front of the pyramid, now dubbed “the old cemetery”. Eventually, so as to not obstruct the view of the pyramid, the area surrounding the pyramid became closed off for burial and new trees and so the cemetery was expanded.

The new part of the cementary, as seen from the entrance, featuring the abundant trees and peaceful greenery, alongside a variety of elaborate tombstones.

A quick glance around the old portion of cemetery will prove that there are relatively few, if any, Jewish tombstones there. During the time of the old cemetery, there was actually a separate Jewish cemetery in Rome, leading to a much different burial experience than that from the Jewish Catacombs. From a quick online search, I can only guess that it is Campo Verano, a cemetery founded in the early 19th century, divided into a Jewish cemetery, a Catholic cemetery, and a WWI monument (most likely those from the bombing of San Lorenzo). However, according to Cimiteri Capitolini, the remains of a Roman Necropolis known as the Catacombs of Santa Ciriaca, render the burial grounds to be at least two thousand years old. The Flaminio Cemetery, constructed in the 1940s, also seems to have a wide variety of religions and nationalities.

One of the Jewish tombstones found in the new portion of Non-Catholic Cemetery. Unfortunately, the cemetery’s database does not have a search function for specific religions.

Curious about the number of Jewish tombstones that I noticed in the Non-Catholic cemetery, I decided to look into the traditions for a Jewish funeral or burial. According to chabad.org, a will must leave specific instructions detailing the circumstances of a funeral and burial: washing and purification of the body (Tahara), a set of traditional shrouds, a kosher casket, and care of the Chevra Kaddisha (Tacrichim), and also, someone to keep watch over the body (Shomer). It is also noted that cremation is forbidden and that the body must be buried under 24 hours, with certain exceptions.

A map of Rome’s Non-Catholic Cemetery, demonstrating it’s size. Note that the far left is the old part of the cemetery, featuring the pyramid. The cemetery then expanded to the right in the 1850s and 1890s.

Through my visit of Testaccio and Trastevere, alongside the Non-Catholic cemetery, I began to realize how widespread Jewish history is in Rome. From the writings of Elsa Morante about entire sections of Rome, to the difficulties associated with burying Jewish within a Catholic country, to the location and civil planning of the Roman Ghetto, I began to discover more and more about the oldest minority. Through our Jewish Italy course, I’ve noticed that many Jewish Italian authors are also some of the most popular authors in Italy. However, visiting the locations that these authors have written about, visiting the historic places where they lived, has added a depth to their literature that I would not have gained otherwise.

Useful Links:

http://www.cemeteryrome.it/about/about.html

https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/367836/jewish/Basic-Laws.htm

Various Influences, Kosher Bakeries, and Il Ghetto: A Trip Down Venetian Lane by Maryam Asenuga

“Venice never quite seems real, but rather an ornate film set suspended on the water.” Words articulated by Italian fashion designer Frida Giannini impeccably delineate my thoughts as I experienced Venice. Captivated by the people, beautiful architecture, and water, the city of Venice constantly had me searching for a person to pinch me to end this whimsical dream. However, the city was in fact reality and so too the events that marked its troubling history.

Picture taken at the end of our tour on 3/14 of this dream-like city.

To begin the tour, our spunky and humorous guide informed my classmates, Professor, and me of Venice’s history that is often unknown to many. She informed us that Venice possessed Eastern and Northern Europeans brought to the city. Along with others, these people were sold for manpower needed for slavery in Muslim worlds. Similarly, our guide explained how Venice was home to Muslims from Persia, Bosnia, Albania, etc. Thus, Arab influence permeated and continues to do so throughout the city. After recounting this history of Venice that I had no prior knowledge of, our tour guide explained the “good” that came out of this muddled past. She said, “The presence and mixing of these many different people shows how ‘contamination’ could be a good thing. I am proud of how mixed my blood is. If someone were to check my blood, it would not be made up of just one thing.” The beauty in this statement and its reality made me reflect upon my initial impression of Venice after told about its dark history with slavery. Although disappointing, this history demonstrated a fact that most people debase today. This fact is the brilliance, not degradation, of different peoples of different lands coming together to influence one another. Many people, especially Americans, extract disgust from people who “mix” with people from other races, and to see our guide’s pride from being of a mixed heritage was something I was not expecting from a city that is seemingly homogenous at first glance.

The plaza, with a rich history, where we began our tour.

Moreover, my classmates and I envisaged how the presence of these different and diverse influencing forces still hold today in Venice as we visited a Kosher bakery and restaurant.

“Panificio Volpe Giovanni”‘

While visiting this Kosher bakery, I discovered something beautifully shocking that bolsters the claim of Venice’s multifaceted nature. Not only is this Jewish and Kosher bakery run by Christian owners, its foods have Middle Eastern and German influences. In addition, we also visited a restaurant of a Jewish nature.

This restaurant continued to challenge everything I thought I knew about Venice. While sitting in this establishment, and basking in its glory, I was in awe of the heavy Jewish influences I saw all around the room. From the Hebrew inscriptions, to the Star of David, and to a beautifully creative Menorah. Before, I believed Venice to be a city of Italians and Italian people, music, and foods only. However, after eating in this establishment, I began to reflect upon the importance of influences in this city that are not only Italian. Or what my conception of “Italian” was before. The bakery and the restaurant were one of my absolute favorite parts of the tours. In Venice, Jewish Italians were executed and sent to concentration camps for the presence of their “differences” and them not being only Italian or whatever “Italian” is said to look like. However, these two places, the bakery and the restaurant, show a juxtaposing side of differences. It shows a more positive light and how the presence of diverse forces can influence things in a way that enriches it, not in a way that leads to persecution.

This restaurant continued to challenge everything I thought I knew about Venice. While sitting in this establishment, and basking in its glory, I was in awe of the heavy Jewish influences I saw all around the room. From the Hebrew inscriptions, to the Star of David, and to a beautifully creative Menorah. Before, I believed Venice to be a city of Italians and Italian people, music, and foods only. However, after eating in this establishment, I began to reflect upon the importance of influences in this city that are not only Italian. Or what my conception of “Italian” was before. The bakery and the restaurant were one of my absolute favorite parts of the tours. In Venice, Jewish Italians were executed and sent to concentration camps for the presence of their “differences” and them not being only Italian or whatever “Italian” is said to look like. However, these two places, the bakery and the restaurant, show a juxtaposing side of differences. It shows a more positive light and how the presence of diverse forces can influence things in a way that enriches it, not in a way that leads to persecution.

Furthermore, as the tour progressed, I finally got to experience my main motivation for taking this course and embarking on this trip: the Italian Jewry and understanding the treatment of Italian Jews. During the tour, we came across two large buildings facing each other. I will delineate the first one, the white building pictured below.

1938

While showing us this building, the tour guide relayed the information of the harrowing history of Jewish Italians. 246 Venetians and 8,000 people from Italy in total were killed during the Holocaust, or “Shoah” (meaning “Catastrophe”). In 1938, the guide told us that people of Jewish backgrounds were harassed by the racial laws in all aspects of their lives. They could not go to schools, shops, beaches, or even work to provide for their families. While describing this history, a history similar to that of my ancestors, our tour guide declared, “My friend’s father, {who at eight-years-old at the time}, was told that he was an enemy of the state.” An eight-year-old? An enemy? Shocked, disturbed, and moved, these words will forever stick with me. Although exploring Italy was and is the best thing to have ever happened to me, it is the knowledge, lessons, and experiences that I gained during this trip and especially this tour that will stick with me for a lifetime. How can innocent people, or even mere children, be seen as enemies? This tour remarkably bolstered my understanding of the Italian Jewry, and irrevocably changed what I thought I knew of Venice and those who previously inhabited it. What is to following may be even more astounding.

La scuola degli ebrei (1920).

Pictured above is the building right across the white building I described above. This building, and our tour guide’s explanation of it, also contributed to knowledge that has helped remarkably transform my prior knowledge and thoughts on Venice. Moreover, the tour guide informed us that Venice attracted various foreign communities, such as Greeks, due to its commodities that helped foster “brotherhood”. These commodities existed as “le scuole” given to foreign communities that arrived in Venice. Thus, for the Jewish, the scuola existed not as a school but as a synagogue. This synagogue functioned as a community that provided social assistance/healthcare, education, social, and religious. Although inspiring that this city helped create a sense of community for foreigners, the juxtaposition between this building and the white one shows a truth about this city’s history that cannot be covered by “le scuole”. These buildings, right across from each other symbolize how in 1920, “Jews were seen as heroes” (red building above), but soon after in 1938, “Jews were seen as enemies of the state” (white building).

Similarly, my absolute favorite elements of the trips were the elements of commemoration of the lives lost placed in Venice (pictured below).

“Stepping Stones”

Arbit Blatas’ 1989 artwork in ghetto di Venezia.

The first image shows two of the 55,000 “stepping stones” in Europe created to provide recognition for all people who lost their life to the Shoah and to ensure that people never forget what happened. The second image is a portrait created by Lithuanian-Jewish artist Arbit Blatas in 1989. The portrait, behind our tour guide in this picture, shows a train that brought people to the concentration camps. In the artwork, one can see limping elderly, men, women, and children all marching with their luggage “hoping it’ll mean something”. The piece also features the names of the 256 people and the dates of their deaths. Similar to the stepping stones, this artwork is to foster the necessaryremembrance of these victims.

In addition, what struck me even more than the beauty of this portrait is a question our tour guide posed to all of us. She asked, “Is it appropriate to place this artwork of the Shoah in a place that used to be a ghetto?” When she asked this question, a question I had not thought of before, I reflected on it for the remainder of the trip. As I went back and forth, I finally came to an answer: not only is the placement of this artwork appropriate, it is obligatory. Regardless of it being in the past, all people, not just Venetians, must be reminded of what happened and the prejudice that continues to happen in this world that led to the theft of innocent lives.

In conclusion, this day, the tour, and the knowledge of the tour guide monumentally contributed to my understanding of the Italian Jewry and the Italians persecuted for their “differences”. The most surprising and significant things I learned today is discussed in the above paragraphs. Before entering Venice, I never thought I would learn that this seemingly homogenous city contains so many Arab influences. As an Arabic-speaker and person interested in the Middle East, this was one of my favorite elements of the trip as I grasped how proud our tour guide was of her city’s multiple influences and her “mixed-blood”. Also, this day grandiosely added to my understanding of Venice, its history, and its Jewish authors. Marred by such carnage and death, this city does not attempt to disregard and cast off its ghastly past, but instead upholds it for us all to remember what occurred to Jews of Venice, Italy, and in other countries. This idea connects specifically to the artwork above, which is the specific site element or object that added to my perspective.

In tandem, this day intrinsically tied to our readings, especially “La Storia”. Due to this day, and supported by prior preparation and teaching of Professor Ziolkowski, I was more equipped to answer the various questions I came into this class with. Such as: What does Jewish Italian or Italian Jewish mean? What does it mean in terms of culture and identity? What does Jewish Italian literature mean and include? How does literature relate to cultural, religious, national, and personal identity? What role has Italy played in Jewish history and Jews in Italian history? All of these questions were answered throughout this trip, but especially on this day, which has helped me understand a fuller picture of what Venice and Jewish Italy is all about. Although its history is saddening, I am happy it remains evident all throughout this city of dreams to remind us that although we are far from these tragic events, we must always ensure we never regress to a world where these events can occur again.

The Star of David. One of the very first things I saw as I stepped into Venice.

A Day in Trieste by Natalie Ecanow and Daniel Rubinstein

After a two hour-long train ride from Venice, we arrived in Trieste. We were greeted outside the train station by a statue of Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. The buildings looked different than those we had seen in Rome and Venice. Immediately, we were reminded of Trieste’s complex identity, marked by both its past within the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its Italian present.

Statue of Elisabeth of Bavaria Outside the Trieste Train Station

We headed straight to the Museum of the Jewish Community of Trieste. On our way there, we came across a statue of Irish author James Joyce, who wrote several of his works while living in Trieste and whose novel Ulysses we had studied in class.

Statue of James Joyce

We arrived at the Museum of the Jewish Community of Trieste, which told the story of the over seven centuries of Jewish presence in the city. We learned that the community originates from a few Ashkenazi families that moved to Trieste during the Middle Ages. Trieste’s Jewish community grew throughout the Habsburg Monarchy, driven by events such as Joseph II’s Edict of Tolerance in 1782 (which granted religious freedom to Jews) and an influx of approximately one thousand Sephardic Greek Jews fleeing Corfu in 1891. After Trieste’s annexation to Italy until World War II, the community continued to grow: before World War II, Trieste housed the third largest Jewish community of Italy (after Rome and Milan).

The exhibits in the museum also explored the lives of many Jewish authors and scholars whose works we had studied in class, including Samuel David Luzzatto, Italo Svevo, and Umberto Saba.

One interesting discovery I made during the visit of the museum was that during World War II, around 150,000 Jews from Central and Eastern Europe transited through Trieste on their way to Palestine (as well as other safe destinations such as the Americas), and that the building where I was standing had in fact served as the local seat of the Misrad, the committee for the assistance of Jewish emigrants.

Next, we visited the Svevo and Joyce museum, where we were greeted by Riccardo Cepach who spoke to us about the unique relationship between authors James Joyce and Italo Svevo, highlighting objects around the room that reflected the history of their relationship and their literary works. One object that struck me was Svevo’s violin that was mounted on the wall. Riccardo explained how the violin, as well as Svevo’s attachment to cigarettes, were two things that Svevo transferred from his life into his characters. This detail added a layer of richness to the character of Zeno from Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience which we read in class. Svevo’s bookcase also stands in the museum, and is monogrammed with the letters “E” and “S,” the initials of Svevo’s given name. This stood out to me as a permanent symbol of Svevo’s Jewish origins.

Italo Svevo’s Violin

Italo Svevo’s Bookcase

After visiting the museums, we headed to Café San Marco for lunch. As we sat at the cafe, I couldn’t help but look around and observe for myself the place that was described in great detail in one of our readings. Being able to physically sit in a cafe that inspired a class reading was an enriching experience. Our lunch in Trieste was one of the most glaring reflections of our readings that we experienced while in Italy.

Bookstore at Cafe San Marco

Our class at lunch at Cafe San Marco

Finally, we headed for a tour of the Synagogue of Trieste, which was completed in 1912 and is the largest synagogue in Italy. There were approximately 6000 Jews in Trieste before World War II, and this large and ornately decorated synagogue was built to meet the needs of this growing community.

The outside of the Synagogue of Trieste. Unfortunately, photos were not allowed inside!

During World War II, other synagogues in Trieste were destroyed, but this one was kept because there were plans to repurpose it once the war was over. Even more surprising, our guide told us that the Torah and other religious artifacts also miraculously survived the war, hidden in a secret room within the synagogue that was only discovered well later during renovations of the synagogue.

Today, the Triestine Jewish community is small (around 560 members) and the main part of the synagogue complex is no longer used, but there are still daily services held. Sephardic rites are used during the weekdays, and Ashkenazi rites are used on Shabbat and for holidays, an interesting reminder of the history of Jewish migrations to Trieste.

Finally, we headed back to the train station to head back to Venice. On the way there, we passed Libreria Antiquaria Umberto Saba where Saba himself once worked, a final reminder of Trieste’s rich literary past.

Bookstore where Saba worked

Jewish Museum and Four Synagogues by Jason Beck

Venice of the Middle Ages and early modern period was not merely a hub for trade flowing between Western Europe and the East but also a hub for peoples from all over. Many Venetians are proud to view their blood as mixed, in the sense that they are all descendants of the various ethnic and religious minorities that were attracted to and resided in the floating city during these periods. Just as the populations of the Christian populations were diverse, so to were those of the Jews in Venice.

Ark in the Ashkenazi synagogue in Venice. Marmorino walls surrounded the prayer hall

The Jews in Venice have had a continuous presence since the 14th century. The Doge and the Venetian government wanted the Jews for their usury since Christian merchants were dogmatically forbidden from charging loans with interest. The Jewish moneychangers were essential for Venice’s primary business: trade. Without the ability to create loans and interest payments, massive, international trade, in which Venice was involved, would be impossible.

The first Jews to come to Venice were the Ashkenazi, coming mainly from the Carinthia region of Austria to escape religious persecutions from the lands of the Holy Roman Empire. The Sephardic community, coming from places such as Naples, Spain, and Corfu, came to Venice following the expulsion of the Jews from the Spanish Empire. The diversity in the Jewish populations led to diversity in religious and social life: despite the persecution of the Jews and the ghetto and their relatively small number, Venice became home to five different synagogues, a German, a French, an Italian, and two Spanish scuole.

Ark of the French synagogue. Hand-cut wood and covered with bronze

The five synagogues were located in the Jewish Ghetto of Venice. Although still a center of Jewish life in the city, most Jews today live in the center of the city. The Jewish ghetto, gated off from the rest of the city, was opened temporarilty in 1797 following the French takeover of the Republic of Venice and permanently in 1866 when Venice was liberated from the Habsburg Empire and annexed to the Kingdom of Italy.

The first synagogue we visited on the tour was the German synagogue, connectly directly to the Jewish Museum. There are three main details about this synagogue which are unique: firstly, like the other synagogues in the ghetto, the German scuola was bipolar, meaning the bimah and the Ark were located across from one another on either side of the oval room. Secondly, the synagogue was surrounded by marmorino, a cheaper alternative to marble. This detail is very emblematic of the situation of Jews living in Venice at the time of the Republic. Church authorities prevented Jews from buying marble to build their synagogues because the material was commonly used in churches. Thus, the community leaders purchased the alternative material. Although the Venetians needed the Jews and their professions for the survival of Venetian trade in Italy and in the Mediterranean, they were still treated as less-than-equals with Christians, and were publicly embarrassed for this prohibition on marble.

Bimah of the Sephardic synagogue. Notice the purposeful error in the floor tiling, showing that only the Divine is perfect

After visiting the other synagogues and seeing the different decorum of the rooms (pictures attached), the question of Jewish identity came into my mind. Because the Jews of Venice created five separate synagogues for their respective communities, the overall community must not have been as united as the Venetians who locked the ghetto thought. The Jews of Venice kept the customs of their homelands, including liturgical rites, language, and cuisine. The diversity amongst the Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto counters the marginalization that church and government officials promoted for this minority on their island.