For the second episode of the Voices of Duke Health podcast, we hear about the Duke Navigators Program.

Duke Navigators was created by medical students Chloe Peters, Cosette Dechant, Leonid Aksenov, Emily Lydon, and Neha Kayastha. They wanted to help their fellow medical students – as well as students in Duke’s nursing and physical therapy programs – to talk with patients about end-of-life care decisions.

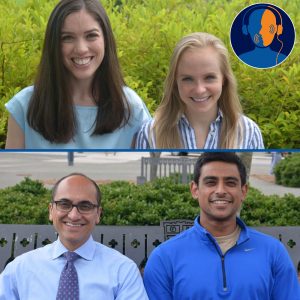

Chloe and Cosette sat down in the Voices of Duke Health listening booth to talk about the idea behind the program. Then, med student Syed Adil and his mentor, Yousuf Zafar, MD, talked about what they’ve learned about conversations with patients and their loved ones.

Listen

https://soundcloud.com/voices-of-duke-health/episode-2-the-hardest-conversation-you-never-want-to-have

Transcript

Karishma Sriram: Five Duke med students have been thinking about the hardest conversation they never want to have. Welcome to Voices of Duke Health. I’m your host, Karishma Sriram. Today, the inside story of how to talk about death. We’re going to start the show by hearing from Chloe Peters and Cosette Dechant, two of those five med students. Here’s Chloe.

Chloe Peters: Basically during our first year in med school, we felt like we didn’t have a lot of formal training on how to talk to patients about dying, how to talk to patients about hard subjects, like what you want the end of your life to look like. Cosette and I just were talking one day and I think we’d both had personal experiences. My grandmother had had Alzheimer’s and the last few years of that were very hard, so we, my family, just spent a lot of time talking about what we wanted the end of our lives to look like.

And so coming to med school, feeling like this was something that I thought about a fair amount for myself, but we really didn’t know how to talk to other people about it. Cosette and I just started talking about, maybe we should make a program or create an opportunity for students to learn how to do this, before you are actually in the position of being a physician, caring for a patient, and having no idea about how to talk to them about something that’s really important.

Cosette Dechant: And also, I think even just recognizing that these conversations are tough, and they’re always going to be a little bit uncomfortable. And at the same time, they are so important, and patients care so much about this. There are a lot of data showing that patients and their families want to talk to their providers about this, and it’s just conversations that, for whatever reason, we aren’t having. So I think we identified that this could be an important area to start talking about, even very early on in medical training.

Karishma: So, they started the Duke Navigators Program, which gives med students a chance to practice talking about death.

Cosette: Kind of a big theme that emerged from this is, people aren’t born inherently good communicators, or this isn’t something you’re just naturally good at. Having these tough conversations is a skill that, just like anything, just like a physical exam, just like a surgery, you practice. And you can gather these tools in your toolkit, these phrases that you can use, or these ways of asking a question. And I think that, for me, was really liberating, to say no, this isn’t something that I just need to feel comfortable with right away. It’s something that you practice, just like everything else.

Chloe: I think that one of the most freeing things is learning how okay it is to talk about this, and learning that by bringing up these topics you’re not going to, generally, cause somebody more pain. Which makes people a little bit more comfortable delving into these issues, I guess, a little bit more.

Most patients actually are really happy to talk about it. Honestly a lot of them find it a relief. I actually had a patient in urology clinic who was very sick with metastatic cancer, and was referred to us because they wanted to know if he needed a very big surgery. I was kind of like, you know, this is probably how your life is going to look for awhile after the surgery as you recover, what do you want your life to look like? And he said, I want to be able to mow my lawn, I want to play with my grandkids, and work on my car. And we said, well, if you have this surgery, I don’t think you’re going to be able to do a lot of that for a very long time. And when we were talking about the possible complications of the surgery, I said, you could be in the hospital for a long time. Or you could die, from this surgery. And afterwards, his brother came up to me and said, I’m so glad you said the D word. Because nobody ever says that word. We have talked to oncologists, we’ve talked to so many people, and none of them have ever said that word. And we all know it’s coming. But it just made us feel like, okay, we can have a conversation here. So honestly, most people welcome it, I think.

Cosette: The people who are these really good communicators and can have these really meaningful conversations with patients are the ones who are willing to listen. If you’re doing most of the talking, you’re probably talking too much. And take the time and be really curious about what’s important in people’s lives and what things matter to them. And these kinds of conversations take time.

Chloe: Don’t use the word “but.” That’s a big one that we learned. When you use the word “but,” you’re negating everything that comes before it. What we learned is to replace it with the word “and.” It feels very awkward at first, but once you do it for awhile, it becomes pretty natural. And it really changes, it just shifts the entire tone and feel of a conversation.

Cosette: So maybe as an example, let’s say a family expresses, you know, we are really hoping for a miracle, or we’re really hoping this next line of chemotherapy works. To say, you know, I’m hoping for that too, but we need to consider what might happen otherwise, if you could instead phrase it as: I wish that for you too, and I think it’s also important to consider what might happen if this doesn’t work, and what you would want that time to look like. You go from sitting at opposite sides of the table, so it’s like the patient is over here and you’re on this other side, talking, kind of at odds. But it brings you around so you’re sitting on the same side of the table as them, saying, I hope this for you too *and* at the same time… And like Chloe said, it really does kind of shift the dynamic of what you’re saying.

The first full iteration of this program that we did was during second year, and I’ll be honest, I was a little bit worried about the amount of work it would take on top of all of the time that you’re already spending in the hospital. And I was worried about, am I overcommitting? Is this going to be adding too much to my plate? And consistently, time and time again, I would find that after coming to these sessions and listening to the just really insightful comments that the students had, and these really powerful experiences that they’d had with their patients, it was rejuvenating, almost. I left every single one of these sessions feeling reinspired about why I came to medicine in the first place. So that’s why I think it’s so important to take the time, even if it is a little bit of extra time, or something extra on your plate, to get involved in things like this. Or to do something like a narrative medicine, or just have a group of people that you regularly talk to about tough things. I think that does a lot in the way of reminding us why we came to this in the first place.

Karishma: Now, we’re gonna hear from Syed Adil. He was one of 18 students who participated in the Navigators Program last year. As part of the program, he was paired with a patient.

Syed Adil: My patient was amazing in terms of sharing his story and always being willing to talk. At first it started with more superficial things, I would say. Because you don’t want to jump right into the heaviest conversations, so we would talk about things like sports and politics, he was a huge hockey fan, and then I was also a huge college basketball fan having gone to Duke for undergrad as well. We would talk about his travels and compare fishing trips. I think as I got closer towards the end, in my fifth, sixth, seventh meetings with him, and as the disease progresses, conversations get more serious, as you also get to know a person. So the conversations started to evolve a bit more towards the end, about heavier things like mortality and all that.

And it’s easy to have a conversation about how to have difficult conversations, but the conversation itself, when you’re face to face with the patient who’s going through it—I found to be much, much more difficult. But I think one of the lessons I’m walking away with is that it’s not always that you have to have the right words to say to them, but just being there to listen, I think, was really powerful, for them to be able to give their story to anybody who is there and willing to listen.

Yousuf Zafar, MD: You know, I think you said the key point there, is that you were there to listen.

Karishma: That’s Dr. Yousuf Zafar, a gastrointestinal medical oncologist, and Adil’s mentor.

Zafar: There’s been a couple really interesting studies about patient-physician communication that have shown that when a physician walks into a patient’s room and patient starts talking, that patient talks for about 12 to 18 seconds before they’re interrupted. 12 to 18 seconds. And it’s for a lot of different reasons, right, but if you think about how a patient is able to get their story out, that’s very hard to do in a limited time. Just a few minutes ago I walked in here from clinic, having seen 14 patients in three hours, right. So we’re in a lot of pressure to see some sick, sick patients in a short period of time. That, however, does not- or should not give us the ability to say, well, we’re just going to rush through this conversation, we’re not going to take the time to sit down and really listen to what a patient says. So what I try to do is to really let, when I walk in the room, to let the patient talk for as long as they need to say something, before I jump in. So for you, Adil, to be there and to be there for him and just listen to what he has to say, is so much more therapeutic than you probably even realize.

Adil: You know, it’s great that you say that, because he actually says the exact same things about you. Because my patient actually had an opportunity to go to a few different hospitals that would’ve been more logistically convenient for him, travelwise, but he said when he was weighing his options initially and he came to Dr. Zafar, Dr. Zafar actually- one of the first things he said was, so what do you think is going on? And he gave my patient a chance to speak. And that was something that he didn’t experience in other places. And I think that was really what convinced him that Duke was the right place for him. So I think it’s really great to have a role model like Dr. Zafar.

Karishma: You know, Adil, you mentioned something interesting earlier, where you said that in the beginning, you tended to have more superficial conversations with your patient, but then as the weeks progressed you began to have more of those serious conversations. But Dr. Zafar, I mean, you’re just saying you see 14 patients within the span of maybe five or six hours. The medical field brings together two complete strangers into this one room, for 15 minutes, to have an incredibly vulnerable conversation. Do you think that that is the right environment to have these kind of meaningful conversations, or- what are your thoughts on that?

Zafar: When I decided to go into oncology, one thing I never really understood at that time, was that the practice of oncology is about 95% communication and about 5% actually doling out drugs. And I never understood that. Because the part that I saw in medical school and mostly in residency was the science behind it. But really, it’s about communication. And I think our specialty, specifically, needs a lot more in education around communication. And to be honest, I think medical education in general could really benefit more from communication education. So, how do we talk to patients? And especially when you’re meeting a new patient with a new potentially life-limited diagnosis for the first time, as I did about 15 minutes ago, and telling that patient that I might not be able to cure their cancer. And that might limit their survival to the timeframe of months rather than years. That has to be done in a way that is both compassionate and meaningful for the patient, but also realistic so that we’re all on the same page.

So, I’ll often ask patients first what’s important to them. And if I understand what is important to the patient, then I can build my conversation around that. So for example, I’ll often have patients that come in asking for more chemotherapy and saying, I want more treatment. When clearly, that’s not gonna help them. So I ask them, well, what’s important to you? And they’ll say, well, their family is important. And living as long as possible and living as well as possible, and those are all very reasonable goals. And so then, knowing what they want, I can explain to them that getting more treatment might take them away from their families, might potentially shorten their lives and would be counter to their goals. So really, it’s about coming at it from the patient’s perspective and understanding what’s important to them first.

So let me emphasize again, do not underestimate the therapeutic value of listening. Just because you don’t know how to prescribe chemo—actually, it’s a good thing that you don’t know how to prescribe chemotherapy—you probably did much more for him than I could do with my poisons. But it’s tough. It is really tough, I think, to have these conversations. I think it’s important to acknowledge that it is emotionally draining. And even though that’s a really challenging conversation to have, to know that I can help that patient through that time with that conversation is incredibly rewarding.

Adil: Definitely. And I think that’s something that, as a medical student, we are all craving. When we came to medical school, we didn’t want to learn how to document notes in aggressive amounts of detail or how to learn the nuances of xyz, but I think having connections with people is what we were most excited about. And when you ask, you know, what keeps you rejuvenated and what keeps you excited about medicine, exactly, seeking out these conversations, I think, is definitely the best answer. Doing that artfully is, you know, a skill and one that you have practice, exactly like Dr. Zafar said. But I am definitely looking forward to being in a hospital setting next year where I can hopefully put some of these skills to use. Listening being first and foremost, I think, the number one skill that will get to practice.

Zafar: You know, I think about, Adil, you know, the interactions that you had with this patient. And what I would encourage you, and all, you know, medical students and trainees, is to seek out those conversations early. Because I guarantee you that this relationship will stick with you for the rest of your career. And it’ll inform everything that you do. So if you can have these conversations early on, you realize the importance of them and the power of them. They will shape how you practice medicine.

Adil: I think the joy of being in medicine is getting to know people. Obviously it’s a sad environment, the hospital, too, it’s not like you’re getting to know somebody through the happiest moments of their lives, it’s the opposite. But I think a lot of the beauty of humanity is that we can connect, even with strangers, when we’re in such vulnerable positions. And I think just getting to know each other is one the absolute coolest things about being in medicine, and I think that that gives us joy even in these hallways where so oftentimes it’s a dark place, especially for the patients, to be able to find the light. And being with each other is something that’s really powerful.

Karishma: A big thank you to Dr. Zafar, Adil, Chloe, and Cosette for sharing their stories with us.

Cosette: Well, we just want to say thank you guys so much for letting us come here and share our story. And also a huge thank you to our mentors: Dr. Trig Brown, Dr. Karen Kingsolver; our classmates Emily, Leonid, Nicole, Aaron, and Neha, who have helped us bring this program to where it is. And also a huge thank you to all of the oncologists who have worked with us and the faculty members who have helped us put these workshops together and really bring this program to where it is today. Thank you guys so much.