The novel we’ll be reading for the next two weeks, Texaco, is a sprawling historical epic by Martinican writer Patrick Chamoiseau that attempts nothing less than to tell the story of the people of Martinique from slavery to the present day. It is divided into two “books,” or “tables” in the French version, the first about the 19th century and the second about the 20th century. For next week, please read the first “table.” Pay attention to the ways in which Chamoiseau attempts to tell the history from the bottom up, infusing larger historical events with the everyday experiences, hopes, desires, and relationships of individuals and communities. Pay attention, too, to the use of language, which brings together some creole phrases, references to the landscape and fauna of the island, and a way of writing that is meant to communicate some of the forms of oral story-telling and historical memory in the place he is trying to represent.

This is a long and complex book, so if it helps I would suggest concentrating in particular as you read this first “table” on the issue of freedom and emancipation. How, in Chamoiseau’s narration, did freedom come to Martinique in 1848? What did it mean to the former slaves? How did they attempt to construct a true form of autonomy and freedom in the wake of slavery? One key section that deals with these issues is the “Noutéka des Mornes” that starts in the French edition on page 161.

In the comments section below or in a separate post, write about one of two things: 1. About your favorite passage from the book so far, and why you think it is particularly important or meaningful or 2. About how Chamoiseau illustrates and explores the meaning of “freedom” both as a political and personal process in the novel. Please share your thoughts by Wednesday at 5 p.m.

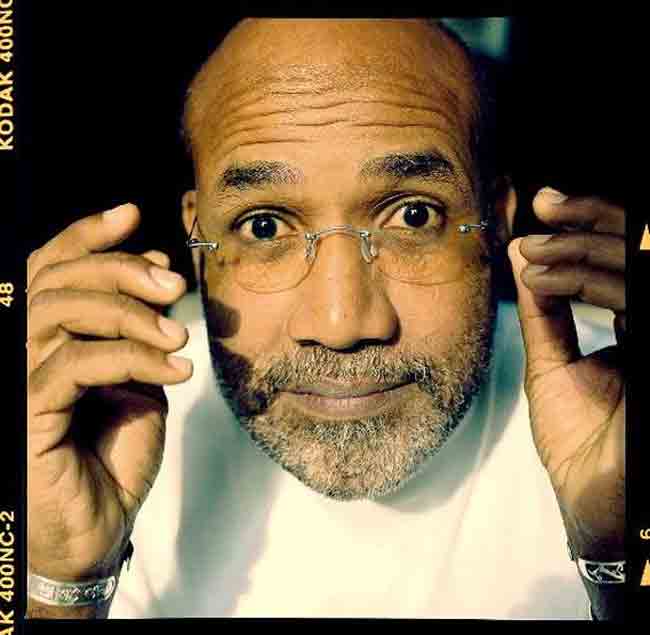

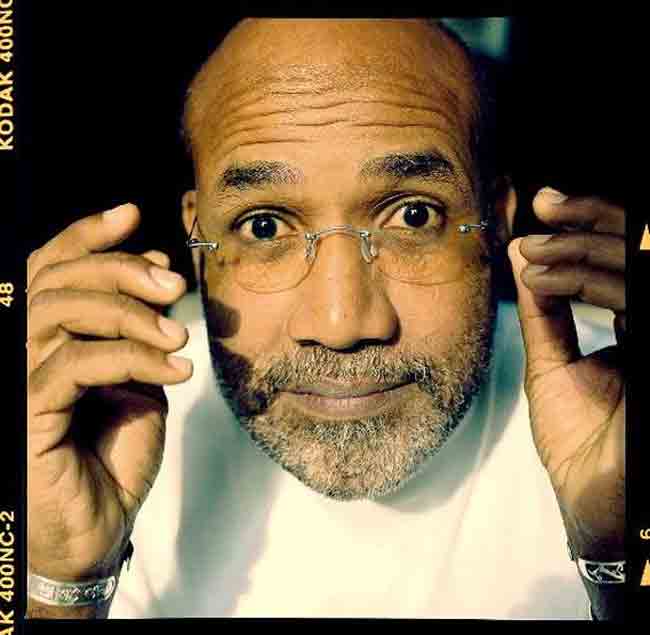

If you would like to know more about Patrick Chamoiseau this site offers a biography and complete bibliography of his works (in French).

Here is a review in English from the New York Times of the translation of the book.

And here is a video of a television interview with Patrick Chamoiseau after he won the prestigious Prix Goncourt (France’s most important literary prize) for Texaco.

Here is a recent text by Chamoiseau about racism.