How to Respond to a Water Crisis

by Ryan Bronstein

Water is the epitome of the Anthropocene. Nothing in this world is so omnipresent, so overconsumed, yet now so scarce to mankind. Though water is an inherent basic right, as declared by the World Health Organization in 2010, today it is primarily viewed as a commodity. Water stocks are traded every day, and in some places water is already a privately distributed good. This perspective of water as a commodity has widened the disparity between those who have access to clean water and those who do not. Further exacerbating this inequity is climate change, as aridification becomes more prominent, especially in low-income developing nations. The result: 783 million people do not have access to an improved water source — one free from outside contaminants (CDC 2016). If the world continues on the path it follows today, then the future of clean water is bleak. Nevertheless, response to the many water crises worldwide is growing, in large part because they cannot be put off any longer. This essay aims to explore these global responses in order to form an understanding as to why water, amidst the global age of innovation, is somehow still not accessible to millions of people on this planet. By studying the responses of governments in Israel, Mexico, Bolivia, the United States, and South Africa, to their own water crises, I will attempt to uncover the future of water distribution, answering questions such as if water will ever be accessible to everyone and if so, how it might be done. Additionally, I will look towards Duke University and their efforts for how water consumption may be reduced on a smaller scale, and predict whether these same methods could have large-scale applications. The Global Water Crisis is beyond merely a complex issue. It is a wicked problem, and it is of the utmost importance for the future of our livelihoods and our children’s livelihoods that our response today is as organized and effective as possible, and in order to do that, we must take a closer look at what is currently being done.

Israel

In the Middle East, crisis has always been present. As countries in the region struggle with countless economic, social, and political issues, including the fall in the price of oil, dictatorships, poor foreign relations, and the constant threat of war; water has become a new source of turmoil. The worst drought in the Eastern Mediterranean in the last 900 years has plagued the inhabiting countries since 1998, with a peak in 2007 (NASA 2016). In Syria, the most vulnerable farmers, roughly 1.3 million people, suffered 75 percent total crop failure. Furthermore, 85 percent of their livestock was lost, forcing approximately 500,000 people to move into the cities (Powell 2016). In 2009, the United Nations estimated the damages and reported that over 800,000 Syrians lost their entire livelihoods to the drought (Femia & Werrell 2012). In Jordan, the drought proved to be devastating as well. Its dams built to secure a water supply are now holding only 43 percent of their capacity as a result of increased evaporation and the repurposing of water to go towards irrigation. Nevertheless, the consequences of the drought were not as harsh in Jordan as they were in Syria thanks to the help of Israel.

Until 2009, Israel faced grave danger as a result of the drought, just like the rest of the Middle East. Its largest source of freshwater, the Sea of Galilee, was inches away from irreversible salt infiltration; and farmers suffered mightily, many losing an entire year’s worth of crops. Yet, amidst its many conflicts, Israel prioritized its water crisis and set themselves apart from their neighbors. While Syria was largely forced to focus on its political issues and Jordan worked towards creating a system that could warn of droughts, Israel attacked the problem head-on.

Fig. 1 A map displaying the severity of the decade-long drought in the Middle East as of 2008 (Hearse 2010).

The fight against the drought began in 2007 when Israel made a commitment to decrease its water usage. Through the implementation of low-flow toilets and showers across the nation as well as the construction of water treatment plants, Israel became a world leader in the efficient use of water. The country is now capable of recovering 86 percent of drained water, and this water goes to advanced forms of irrigation, such as drip irrigation (Jacobson & Ensia 2016). Even with the help of these systems, Israel’s rate of replenishment of water was still lower than the rate of disappearance. To solve this, Israel turned towards it greatest innovation yet: desalination.

In 2005, Israel constructed its Ashkelon desalination plant. Then, due to its success, Israel built the Hadera plant four years later. In 2013, Israel finished construction of another desalination plant, called Sorek. Today, Israel has five plants that, put together, are capable of turning over 600 million cubic meters of salt water into potable water. Today, the nation gets over 55 percent of its domestic water from desalination (Jacobson & Ensia 2016). Though these plants did not come cheap — the Sorek plant came with a US $500 million US — Israel is already reaping the benefits. The Sea of Galilee has been saved from irreversible salt damage and the agriculture industry has too been saved. Now, Israel is in a situation unimaginable 10 years ago: it has more water than it needs.

Fig. 2 The Sorek Desalination Plant. Photo from IDE Technologies.

The drought did not strike Jordan as strongly as it had struck Syria because of large shipments of Israel’s excess water. Since 2005, Israel has supplied Jordan with 50 million cubic meters of water, and in 2010 that number was doubled in exchange for future shipments from Jordan’s soon to be built desalination plant (Dotan 2016). Clearly, desalination will play an integral part in supplying Middle Eastern citizens with water for the foreseeable future. Even though it is too expensive for some countries, such as Syria, to fund, Israel and Jordan can become essential distributors, and in doing so, they may also become distributors of peace. For example, Israel’s decision to ship more water to Jordan was primarily made to support the large number of Syrian refugees that Jordan is absorbing. In return, the future shipments of water from Jordan to Israel will go towards Israeli agriculture. This mutualism between these nations may very well be the future of Middle Eastern interrelations. It is difficult to imagine anything bringing peace to the Middle East, but it is far more unimaginable to see these countries still fighting if they do not have any water. To be without water is to be without life, and without life, what is there left to fight for?

Despite its grand rewards, desalination is not yet a perfect solution to ending water crises worldwide. As mentioned, the fixed costs of constructing such plants exceeds the hundreds of millions, eliminating this as an option for many countries, including some that will be mentioned in this paper. Furthermore, Israelis are facing negative health consequences from desalinated water. The supply is too low in magnesium and has already increased the mortality risk of heart disease (Rinat 2017). To add magnesium to the water will be an additional cost that makes desalination even less affordable. Until the construction of these plants becomes more economically viable, other methods will have to be put in place to combat water shortages.

Mexico

Mexico is currently facing its own water crisis, one with a time bomb set to explode even sooner than Israel’s had ever been. As of 2015, about 3.9 percent of Mexican citizens, or approximately 4.8 million people, lack access to an improved water source (The World Bank 2015). Furthermore, consumption of water from contaminated sources is responsible for 8 percent of Mexico’s total disease burden, including increased incidence of diarrheal diseases, chronic kidney disease, intestinal infectious diseases, and lower respiratory infections (IHME 2015). As Mexico struggles today to provide its citizens with one of their most basic rights, the future is even more dim.

Human-caused climate change is increasing the amount of desert in Mexico, thereby increasing water demand and decreasing water supply. One region that will especially feel the consequences is Iztapalapa, a borough of Mexico City. This neighborhood has a rapidly growing population, as well as a rapidly growing water demand. Home to 1.8 million residents and a population density approximately 1.5 times that of New York City, Iztapalapa is not prepared to adapt to a diminished water supply. Currently, Iztapalapa brings in water from the wealthy town of Cutzamala, located 150 km away, through pipelines. However, Cutzamala obtains its water from their own drying dam. Ignoring the receding level of their dam, water is pumped continuously pumped out in Cutzamala at a rate of 14 kg/cm2. For comparison, this is 28 times faster than water is pumped in Mexico City’s most impoverished borough, Iztapalapa (Watts 2015).

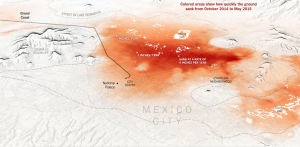

As is evident by the water pressure differences, less water is received by Iztapalapa — where the population is higher — than is consumed by Cutzamala. Exacerbating this issue is the method of transport between the two boroughs. Water travels 150 km through a series of poorly engineered pipelines. These lines are full of fissures and leaks that lead to a more contaminated and reduced water supply. Moreover, water is pumped by gravity, which is increasingly becoming a problem as Mexico suffers from man-made sinkholes. As Mexico has no large-scale wastewater reclamation or rainwater collection processes, it is dependent upon aquifers to even attempt to meet its water demand. By drilling into the ground to reach new aquifers, the clay beds underlying the surface are broken up and susceptible to fissures. This leads to tremendous sinking; in some areas, the ground sinks as much as nine inches per year (Kimmelman 2017). This uneven subsidence reduces the efficiency of the gravity-dependent pipelines, thereby decreasing the amount of water that makes its way to Iztapalapa. As a result, it is predicted that ten percent of Mexicans ages 15-65 could try to emigrate north in response to the subsidence and recurrence of droughts brought to the region by a changing climate (Kimmelman 2017).

Fig. 3 Depicted here is a map of Mexico City displaying the various rates of subsidence, illustrating the gravitational inefficiencies that arise out of the pipelines. Data gathered from Dr. Andy Sowter at Geomatic Ventures Limited.

Clearly, Mexico has a water crisis. Already millions of people lack access to clean water, especially the poor, and that number is only expected to rise as climate change continues to expand its influence and wreak havoc. Though the problem is quite apparent and easy to identify, the solution is not. Simply put, Mexico does not have sufficient resources. The debt is already 54 percent of the GDP (Index of Economic Freedom 2017), and the annual GDP growth may as well be non-existent at a mere 1.1 percent (Trading Economics 2017). Therefore, it is unlikely that Mexico can take on projects to increase the water supply. Reconstructing the pipelines, repairing leaks, or creating rainwater collection systems are all too large of projects for Mexico to take on, at least according to its major political groups. Thus, certainly desalination is also far too expensive for the Mexican government to move towards. So what is left? What is there for the Mexican government to do? The short answer: practically nothing.

Today, Mexico is leaning towards commencing the privatization of its water supply. In fact, one of the leading political ideologies pertaining to water comes from Mexico’s center-left political group which proposed the General Water Act that would allow private firms to control the water supply system (Watts 2015). This could go one of two ways for its citizens: first of all, if stakeholder companies come in and commit themselves towards ending the disparity that exists between high-income and low-income households, then this crisis may be largely relieved. Private corporations are more likely to be able to afford improving pipelines or even building desalination plants. On the other hand, if shareholder companies come in and commit themselves to profit, then they will sell water primarily to high-income families and grow the disparity. The latter possibility is what Mexican citizens fear, so much so that they have already begun their rebellion. The proposal of the General Water Act quickly led to massive demonstrations, especially in Tijuana. It is becoming clear that Mexico is willing to accept civil unrest in favor of water privatization as their means of dealing with the water shortage. Nevertheless, the government must proceed with caution because if they let the profit-driven companies take over the water supply, the “Mexican Water Crisis” would quickly become the “Mexican Water Wars”, and perhaps as soon as the year 2020.

Fig. 4 The view of the rapidly growing borough of Iztapalapa where the population density exceeds that of New York City. Picture sourced from The Guardian 2015.

Bolivia

In Bolivia, the response to the water crisis has worked in the opposite direction relative to Mexico. Privatization swept through the country as early as the year 1999 under the directions of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The Bolivian economy had suffered lackluster growth and high inflation, forcing the government to accept a US $138 million loan from the IMF. In exchange, the structural adjustment policies of the IMF required Bolivia to sell all its public enterprises, including its public water agencies (PBS 2002).

In September of 1999, Bolivia leased the water system in Cochabamba, its third largest city, to the consortium Aguas del Tunari on a 40-year concession. Additionally, the government passed law 2029 that required residents to pay the full cost of water services, including those for drinking water. Aguas del Tunari had stated that rates would only rise 35 percent to cover the fixed costs of expanding their services; however, in just three months, prices had already doubled for most households and tripled for some. By January 2000, peaceful protests broke out, and by February, they turned violent. Over the next two months, violent marches and riots took place, often having to be broken up by police. The result was 175 injuries, over 20 arrests, and one death. Most importantly, it resulted in the repeal of Law 2029, and the return of water services to public hands.

Fig. 5 A view of one of the marches of the Cochabamba Water War (Bertoni 2013).

Similar protests broke out in La Paz, Bolivia, but it was not until the year 2005 that water services were returned back to the public. The events that took place are referred to as the “Cochabamba Water War” and this illustrates the incoming dangers in Mexico as it moves towards privatization. Since the war, Bolivia has again suffered from water shortages, in large part as a result of poor management of public water agencies. Today, however, Bolivia faces a growing cause for concern, one that will not be resolved so quickly.

Climate change is ravaging through the Bolivian water supply at an accelerating rate, especially in La Paz. Here, the people depend on glacial runoff for their water. However, since La Paz sits in the high tropics, temperatures are rising. In fact, average temperatures have risen 0.33 degrees Celsius in the last decade, and this has caused glaciers to recede. Lands are becoming dry and rainfall is largely on the decline. In the last 15 years, average annual rainfall has decreased by 20 percent; and it is expected to decrease by another 10 percent as soon as the year 2030 (Kaufman 2017).

La Paz is drying rapidly in what is called a positive feedback loop. The temperature increase of 0.33 degrees Celsius seems small, but it leads to precipitation in the form of rain rather than snow, thus leaving the glaciers un-replenished. This then leads to more melting and more rains doing the same. Overall, glaciers have been receding in Bolivia at a rate of over 40 percent since 1985 (Martinez 2017). The truly unfortunate aspect of this crisis is that Bolivia is hardly at fault. The nation is only responsible for 0.35 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, while the United States is responsible for 14.4 percent. Due to Bolivia’s location and elevation, its glaciers are hit by the impact of the United States (Kaufman 2017). Therefore, there is no sign that climate change will subside in Bolivia because there is little to no evidence of a great change coming to the amount of emissions released by the United States.

The consequences of the water shortage in Bolivia seem as though they came from a fictional movie about a dystopian society. The water supply is currently being run by a water general, who is in charge of directing the routes of water-carrying trucks. The general has instituted a large-scale water-rationing system. For most Bolivians, their daily water consumption has declined from 48 gallons per day to merely 16 gallons, and at times they have to miss work to wait for the taps to turn on and refill their storage tanks (Kaufman 2017).

Managing and rationing water consumption has been the primary response of La Paz to its water crisis; however, two other projects have begun taking work. First, many reservoirs and dams have been constructed to catch rainwater and maintain a steady supply of water. Nevertheless, these reservoirs are not protected from the drying conditions in the region, and too are suffering from the decline in rain as a result of glacial recession. Therefore, the city has also constructed a pipeline to extract water from a creek. Once again, however, the solution is accompanied by its own set of problems. This creek is the water supply for many local farmers, and as water is pumped out at 200 liters per second, it will not be long before it completely dries up. The farmers only response will be to flee to the city of La Paz as climate refugees, thus increasing the demand for water and food in the city. As the reservoirs and the creeks dry up, Bolivia will be left with an increasingly strict water-rationing system and perhaps even a second round of violence. All to little fault of their own.

Fig. 6 Formerly the world’s highest ski resort, the slopes on Chacaltaya mountain above La Paz have been removed of virtually all snow as a result of rising temperatures and drought (Rocha 2016).

United States

Earlier, I referred to the Global Water Crisis as a “wicked” problem. One that is beyond merely complex. The United States, specifically California, illustrates this distinction. Water shortages are wicked problems because even in places as wealthy as California, millions of people lack access to clean drinking water. Indeed, over one million Californians lack access to potable water (Al Jazeera 2015). Of course, this is largely related to the ongoing drought in the southwestern United States — its worst drought in over a century. However, inequitable water allocations have a long history in California, and have played a key role in who holds water and power within the state today.

The current drought, though the most severe, is not California’s only recent drought. In the 1960s, the state responded to its shortages through the construction of dams and aqueducts. Thereby bringing water to places without water. Additionally, the government accelerated the tapping of aquifers, taking advantage of water that fell to the Earth over 20,000 years ago. Even parts of California without groundwater were rapidly turned into some of the most fertile regions the world had ever seen. However, over time the dams began to dry up as we have seen in other parts of the world. Furthermore, the digging of wells could only last so long. After thousands of wells had run completely dry, more and more regions were left without groundwater.

This has had disastrous effects on local residents. Tulare County, for example, had been hit most hard by the California drought in the 2000s. Residents relied on private wells which ran dry and left some residents with only plastic bottled water, which of course has its own environmental impacts. In a 2016 National Geographic film, “Water & Power: A California Heist”, citizens of Tulare County described their new lives without access to clean water. One resident explained how he could no longer clean his clothes or wash the dishes consistently. Therefore, he was forced to resort to plastic plates and dirty clothes. Additionally, his only options for a shower were either at a friend’s house miles away, or he would check listings on Craigslist from people selling five dollar showers. Most dramatically, he and his fiancée could not even consider when they would start a family because how could they take care of a child if they did not even have the resources to take care of themselves?

Fig. 7 Residents of Tulare County leading a water drive amidst the drought (Focusing on the Drought in the Central Valley 2014).

With billions of dollars comprising its budget and an elaborate system of pipelines, how could California leave an entire county with zero water? Just as the 2008 Financial Crisis flowed through the banks, the current water crisis and growing disparity in California has also arisen out of a banking system. However, these banks are not ordinary. These make up a unique and special system, created in 1994 under the Monterey Amendment, a pact made between the Department of Water Resources and State Water Project contractors. Amid yet another drought, this pact was made between groups with very different views for the future. One group represented urban areas, while the other represented the agriculture industry. It was clear that cuts in water usage needed to be made, but who would make them? For days, impassioned fights took place. Just as Mark Twain is attributed with saying, “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting.” After bringing in a mediator, the two groups came together and produced what seemed like a great plan: water banks. In times of wet seasons, Northern California cities would pump water down to water-stressed regions, such as the San Joaquin Valley, and refill depleted aquifers. Then in times of drought, these regions would have an abundant supply they could rely on. Nevertheless, as valuable as water banks could be, they proved equally detrimental when placed in the wrong hands.

Water banks were claimed to be public property; however, their riches actually lie in the hands of the land owners above them. Recognizing the great profits to be made from the growing demand for water, private organizations have formed public-private partnerships in order to control the water supply. For example, Harvard University has spent over $60 million on 10,000 acres of land in the wine country of Paso Robles, California (Philpott 2015). Yet this land lies directly over one of the deepest areas of a large aquifer. Though the drilling of the aquifer must by law be offset by equal conservation, regulations always have expiration dates. For now, Harvard is drilling into sixteen wells to support the irrigation of its grapes and wine, an expensive and highly exported good; however, it is undeniable that unless the land stays heavily regulated, Harvard is practically sitting on a gold mine as the drought worsens (National Geographic 2016).

As private organizations take control of the water supply, an increasing amount of water is being directed towards agriculture, as evident by the investment of Harvard into a vineyard. In fact, though agriculture makes up only 2 percent of California’s economy, it receives 80 percent of the state water supply (National Geographic 2016). This allowed the industry to raise revenues each year between 2010 and 2013, despite the worst drought on record. Wine is just one of the many cash crops being exploited by private investment. The two main culprits are almonds and pistachios. As land-owning firms wait for the chance to sell their water, they raise water-intensive crops that maximize profit. Though a single almond requires about a gallon of water for its production, California produces 80 percent of the global supply. In 2015, over 680 billion gallons of water went towards almond production alone (National Geographic 2016). Had even a tenth of this water gone to the one million citizens without clean water, everybody in California would have enjoyed an abundant supply. Instead, every resident had to cut their water usage by 25 percent, millions of people depended on bottled water, and some residents were buying showers on Craigslist; all so that developed countries like Spain, Germany, and China could enjoy some almonds (Romero 2015).

Fig. 8 Pictured here is a vineyard owned by Brodiaea Inc, the Harvard owned investment firm (Klein 2015).

The water shortage in California is wicked. Though climate change is accelerating, the current problems faced as a result of the shortage could potentially be solved in the short term, perhaps by something as simple as ceasing the production of almonds. Nevertheless, this would result in job loss and billion dollar economic losses. Even though these could be recuperated, some private companies with shares in the industry may never recover, resulting in further job loss. It is difficult to say what exactly needs to be done because there is no perfect solution. There are only things that would be good enough. Yet with millions of people, and growing, lacking potable water and a reasonable standard of living in the United States, we are simply not doing well enough.

Duke University, on the contrary, is trying to do well enough. It has recognized the harmful effects of its carbon footprint and has ignited a great commitment on campus to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and water consumption. It acknowledges that the United States is largely responsible for worldwide desertification and aims to set itself apart. After a devastating drought in 2007, Duke responded the way a billion-dollar institution should: it reallocated its resources and went to work. Since 2007, water consumption on campus has decreased by 40 percent and greenhouse gas emissions have decreased by 23 percent (Sustainability Strategic Plan 2017).

This 40 percent reduction did not come through a single entity. The work began with sequential water audits in the years 2008, 2012, and 2013. What these found is that in buildings across campus, especially in the relatively newly constructed Levine Science Research Center, high-flow water systems and ongoing valve maintenance were proving both costly and inefficient. It was deemed that low-flow diaphragms would pay for themselves within just a few months. The audits also found that the many auto-flush valves on campus grew more inefficient over time as older batteries could not limit flows as well as intended.

With every audit has come new changes to the ever-adapting campus. Duke has installed over 3,000 low-flow aerators in bathrooms, 3,000 low-flush valves on toilets and urinals, and 500 low-flow showerheads. Additionally, 100 million gallons of water per year is now being saved due to the construction of a reclamation pond, which captures 22 percent of runoff and sends it to a chilled water plant to be pumped to various buildings (Sustainable Duke 2017). As a result, many buildings have greatly increased their water savings, as depicted in figure 9 below.

Fig. 9 This graph displays the reductions in water consumption by various buildings on Duke’s campus in the year 2014 (Duke Facilities Management Utilities & Engineering Services 2014).

Even Duke Athletics have begun to go green. Installations made since 2007 include drought-tolerant landscaping, irrigation systems for athletic fields through reclaimed water, cisterns to collect water for the field hockey field, and larger irrigation ponds on the golf course to increase natural water storage (Duke Sustainability 2017). As continued enhancements are made, athletic facilities are projected to save over 2 million gallons of water per year.

By reducing its water consumption, Duke has benefitted from greater drought protection and vast economic savings. Yet these actions have other far-reaching implications. Duke is becoming a leader in the movement towards sustainability and is growing in influence. Furthermore, it is on track towards becoming a carbon neutral campus, which would certainly inspire other top universities to follow suit. The importance of influence cannot be stressed enough because in an increasingly globalized world, every drop of water and every emission is becoming increasingly harmful to let go to waste. This is having devastating impacts worldwide, particularly in developing nations like South Africa.

South Africa

At the southern tip of Africa, South Africa lies especially susceptible to the effects of climate change. With an inefficient government, growing poverty, an HIV/AIDS epidemic, and a heavy reliance on a dying fishing industry; this developing nation is a long way from prosperity. Unfortunately, these issues often leave its water crisis overlooked. As a result, the water crisis is growing at an accelerating rate. In 2015, 6.8 percent of the South African population lacked access to an improved water source (The World Bank 2015).

Climate change has exacerbated all the problems that come with the water shortage which arose out of the apartheid and a poor government. What makes South Africa unique from the other countries I have focused on is that it does not have the resources to formulate its own response. Even as other countries fail and open their supply to privatization, South Africa would have a difficult time attracting firms, essentially closing most options for improvement. Their best hope is that developed nations like the United States quickly end their own disparities and provide aid to the region. In the meantime, desertification reigns over the region.

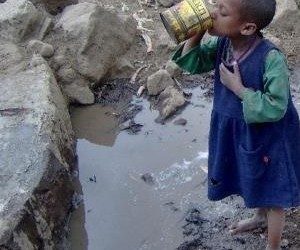

Currently in the middle of its worst drought in 24 years, the South African government has been slow to respond. Even as water levels diminish, the government refuses to declare the situation a state of emergency, thereby withholding funds that would otherwise go towards alleviating the effects of the drought. In Durban, the third most populous city in South Africa, the dams have 20 percent lower levels than they did in 2010 (The Water Project 2017). Moreover, cities like Durban are experiencing growing populations as dry conditions force farmers to leave rural areas. Thus, the demand for water is increasing as the supply is reduced. In fact, the demand for water is now so great, that no drop is safe. Approximately 35 percent of the water supply of Durban is stolen or distributed through illegal connections (The Water Project 2017). The government has been irresponsible by ignoring this issue, as well as by not providing any hope for the future. Even the preventative measures it planned to put in place, such as the construction of dams, have gone uncompleted. As 15 million people lack clean water and sanitation, nations like the United States with the necessary resources for assistance turn their heads and focus on problems that are somehow deemed more urgent (such as the sale and exporting of almonds).

Fig. 10 A child drinks from a contaminated water source in South Africa (Muller 2015).

Meanwhile, diarrheal diseases make up 2.14 percent of the total disease burden in South Africa and are the cause of 20 percent of under-five deaths (IHME 2015). This is a horrifying statistic. Nobody should die of diarrhea. Diseases like cholera are painful beyond the imagination, and as kids are especially susceptible, these diseases destroy lives before they have even been lived. Every day, 2,195 children die of diarrhea globally (CDC 2015). These deaths can be prevented with simple, low-cost interventions such as the distribution of water filters. This is a moral issue; it should not come down to economics. Nevertheless, it should be stated that a $1 investment in combatting diarrheal diseases yields a $25.50 return. There is no reason the South African government should be putting this issue on hold. All of these numbers are only projected to grow as climate change is accelerated. It should be both South Africa’s goal, and the goal of the United States, that nobody dies of diarrhea tomorrow. We can solve this quickly, therefore we must. Tomorrow, there will be 2,195 children in agonizing pain begging for help. How can we ignore them?

Conclusion

This essay has examined some of the many water shortages worldwide. It has explored the roots that brought about these crises as well as their countless consequences. Clearly, there is no simple way to solve this issue. Desalination is promising, but in many areas it is too expensive. Diverting water sources to meet one’s needs also displays potential; however, it leaves behind the same consequences just on different people, such as small farmers. Privatization certainly could be the cure, yet it carries just as much potential to grow water disparities and is often received with violence from the public. Worst of all, there are impoverished nations like South Africa with so many governmental woes, that no solution could even be good enough. So what do we do?

The best way to face the Global Water Crisis is through in depth studies and rapid action. Desalination, assuming sufficient magnesium levels are added, has proven to be a great answer. In countries or regions that can afford such plants, construction of facilities should begin immediately. Furthermore, though privatization runs the risk of facing rebellions, this is not the case everywhere. For example, 60 percent of the French water supply is run by private firms, yet there has been no water war. For over 25 years, every French citizen has had access to an improved water source (The World Bank 2015). In countries considering privatization, it should be encouraged to the public and also heavily regulated to reduce price inflation. These regulations should be as strict as necessary. Even in California, where Harvard is banned from new drilling into the aquifers it lies over, tighter restrictions are needed. If private firms with stakes in the agriculture industry were required to distribute 30 percent of their water consumption amongst the public, rather than towards exported cash crops, then every California resident could have an ample water supply during this devastating drought. All of these solutions can be successful, and at some point in the near future, they will be implemented because governments will simply have no other choice as public unrest grows.

Nevertheless, these solutions do not yet have the same potential in countries like South Africa. Though they could be even more beneficial in such impoverished regions, there is not yet a leader in global health that is implementing these systems. Developed nations and private organizations must form public-private partnerships and become that leader. The problems at hand are not merely economic; they are moral. To solve them, the world needs a movement, led by a change in perspective that ridicules business-as-usual and embraces mutual helpfulness. Though climate change has shown that it has the power to lead the demise of mankind, it could also become our greatest triumph.

Works Cited

Ackerman, Frank. “Climate Change and the Water Crisis in the US Southwest.” Truthout. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

Bertoni, Ruben Chi. “Cochabamba per Ruben Chi Bertoni.” Catalyst.uw.edu. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Bolivia – Leasing the Rain.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, June 2002. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Climate change contributes to worst Middle East drought in 900 years.” Middle East Eye. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Drought threatens water supply, crops – officials.” Jordan Times. N.p., 11 Feb. 2014. Web. 04 May 2017.

El Nasser, Haya. “More than 1 million Californians don’t have reliable access to clean water.” Al Jazeera America. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“GBD Compare.” Data Visualizations. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Global Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (WASH).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17 Dec. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Guzman, Zack. “California’s Drought is Worst In Over a Century, Analysis Shows.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, 16 July 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Hearse, Phil. “Resource wars and the Middle East.” Mid East Resource Wars. N.p., 16 Jan. 2010. Web. 04 May 2017.

Hille, Karl. “Drought in Eastern Mediterranean Worst in 900 Years.” NASA. NASA, 01 Mar. 2016. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Improved water source (% of population with access).” Improved water source (% of population with access) | Data. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Israel to double water supply to Jordan – Globes English.” Globes. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

Jacobsen, Rowan, and Ensia. “Israel Proves the Desalination Era Is Here.” Scientific American. N.p., 29 July 2016. Web. 04 May 2017.

Kaufman, Leslie. “La Paz adapts to a world without water.” Popular Science. N.p., 21 Feb. 2017. Web. 04 May 2017.

Muller, Mike. “South Africa is failing to rise to its water challenges.” The Intelligence Bulletin. N.p., 20 Nov. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Philpott, Tom. “Harvard is buying up vineyards in drought-ridden California wine country.” Mother Jones. N.p., 31 Jan. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Pierce, Charles P. “What Happens When the American Southwest Runs Out of Water?” Esquire. N.p., 13 Oct. 2016. Web. 04 May 2017.

Rinat, Zafrir. “Desalination problems begin to rise to the surface in Israel.” Haaretz.com. N.p., 05 Feb. 2017. Web. 04 May 2017.

Rocha, Jan. “Bolivian water crisis as glaciers vanish.” Climate News Network. N.p., 26 Nov. 2016. Web. 04 May 2017.

Romero, Christina. “Almonds.” Ag Marketing Resource Center. N.p., Aug. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Simeral, Christen, and Cat Boardman. “Even in the U.S. Access to Clean Water Can Be Tough.” U.S. News & World Report. U.S. News & World Report, 12 Aug. 2014. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Sustainability: Water Conservation.” N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Syria: Climate Change, Drought and Social Unrest.” The Center for Climate & Security. N.p., 07 Dec. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

Valdmanis, Richard. “Harvard buys up water rights in drought-hit wine country.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 22 Jan. 2015. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Water & Power: A California Heist.” National Geographic Channel. N.p., 22 Mar. 2017. Web. 04 May 2017.

“Water In Crisis – Spotlight South Africa.” The Water Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.

“With melting glaciers and mining, Bolivia’s water is running dangerously low.” Public Radio International. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 May 2017.