“Crypto is scaling so quickly but security systems are still the same as they were in 2013.” Those are the words of Daniel Chong, a recent Duke student whose new startup aims to change that.

One of the largest challenges within cryptocurrency is security. The most impactful application of cryptocurrency thus far is decentralized finance (DeFi). DeFi eliminates intermediaries by allowing people and businesses to conduct financial transactions through blockchain technology as opposed to working through banks or other corporations. However, as a result, people are personally responsible for securing their assets.

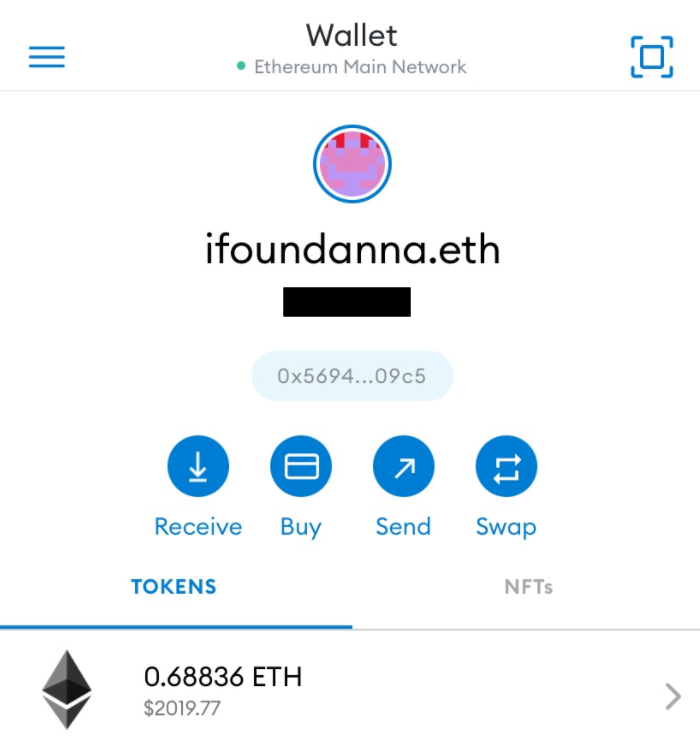

When engaging with cryptocurrency people generally use a trading platform and a wallet. Cryptocurrency trading platforms like Coinbase, Binance, and Crypto.com allow people to buy and sell cryptocurrencies using USD or other cryptocurrencies. However, in order to use crypto, one must transfer some of it into a wallet.

As with conventional currency, crypto wallets are not required in order to use cryptocurrency but they allow individuals to store their tokens in one place, easily retrieve them and send it to other individuals or organizations (i.e. buying non-fungible tokens). Some of the most popular wallets include Coinbase wallet, Metamask, and Electrum.

These wallets are not only password-protected but provide each user with a seed phrase or a series of words generated by one’s cryptocurrency wallet. This phrase, like a password, provides access to the crypto associated with that wallet.

The catch is, if an individual gets locked out of their wallet and cannot remember or does not have access to their seed phrase, all of their money will be lost. This is a major problem in the space and people have lost millions of dollars to lost seed phrases and inaccessible wallets. In fact, 20% of all existing Bitcoin tokens have been misplaced.

Furthermore, in the past, it was already hard enough to secure one’s crypto wallets but now people have several wallets, each with their own unique seed phrase and passcodes making it all the more difficult. In the Fall of 2020, Daniel Chong, a Duke first-year at the time, identified this wallet security problem.

“Crypto is scaling so quickly but security systems are still the same as they were in 2013.”

Daniel Chong

Having grown up in Las Vegas, Chong was used to fast-paced environments and unique challenges. During high school, Chong started coding as a hobby.

“I just wanted to build something,” he explained

The first project he built was a website for a research paper he had in his high school psychology class. In 2018 Chong was introduced to solidity, a programming language that’s main purpose is to develop smart contracts for the Ethereum blockchain. If you are unfamiliar with blockchain, please refer to my previous article here.

Chong matriculated to Duke during a period of transition, the Fall of 2020. As a result of being sent home due to COVID-19 in the Spring and having to shift to online meetings, many on-campus clubs were struggling. Early on Chong met Manmit Singh, a Junior at the time and the President of the Duke Blockchain Lab.

Even though Chong was only a first-year, he had experience coding in solidity and ended up aiding Singh in revamping Duke Blockchain Lab so students could continue engaging with and learning about blockchain despite the pandemic. Additionally, he ran a virtual course on web3 and solidity development for other club members.

Despite the fact that Chong was attending classes, involved in clubs, and working part-time, he began talking to his brother Noah who was a senior at Georgia Tech about once again, building something.

After working on building a security solution for crypto wallets for about a year, Chong and his brother received venture capital funding for their startup Harpie: a simple crypto protection plan that scales with you.

Chong explained that venture capitalists are very excited about crypto right now, especially back in November of 2021 when crypto was in a bull market and bitcoin was at a market high of 60,000.

Harpie is a web app that allows users to connect all of their wallets to individualized protection plans. This means that if you have a Harpie protection plan and someone hacks your wallet or you get locked out, you can go to the Harpie web app and transfer your funds from the unusable wallet to a new one.

Additionally, users are able to choose the degree of security their Harpie account has. Users can regain access to their fund via email, phone, or (personal recommendation) 2-factor authentication. Ultimately, for $8.99/month you can protect as many wallets, with any sum of funds, as you want.

After working for just over a year, Harpie launched on February 14th, 2022. The next weekend Chong and his brother headed to ETHDenver, the largest Ethereum conference, to promote Harpie and compete in the Hackathon. For those who are unfamiliar, hackathons are competitive, sprint-like events where computer programmers and others are involved in software development work to build something over a condensed period of time.

Over 10,000 people participated in the ETHDenver hackathon in person and over 30,000 participated virtually for over $1 million in bounties and prizes, as well as up to $2 million in investment capital.

While the teams had 36 hours to build a project, Chong and his brother managed to build there’s in 4-5 hours. They did this by quickly creating a front-runner bot/flash bot to help people avoid getting hacked by detecting and halting transactions to unauthorized addresses.

The brothers not only successfully built the bot but also placed top 10 in the overall hackathon and had the opportunity to present their project.

While presenting, Chong also received questions from Vitalik Buterin, the founder of Ethereum. He explained this as a very “nerve-wracking experience” and added that Buterin asked very technical questions such as what the miners’ extractable value would be.

In the future, Chong would be open to entering more hackathons but right now is more interested in growing his startup. Currently, Chong is taking time off from school to focus on Harpie and to, ultimately, revolutionize security systems as they relate to online assets.

“Rest easy knowing your crypto is safe.”

Daniel Chong