Huddled in a small cinderblock room in the basement of Hudson Hall, visual artist Raewyn Turner and mechatronics engineer Brian Harris watch as Duke postdoc Nick Geitner positions a glass slide under the bulky eyepiece of an optical microscope.

To the naked eye, the slide is completely clean. But after some careful adjustments of the microscope, a field of technicolor spots splashes across the viewfinder. Each point shows light scattering off one of the thousands of silver nanoparticles spread in a thin sheet across the glass.

“It’s beautiful!” Turner said. “They look like a starry sky.”

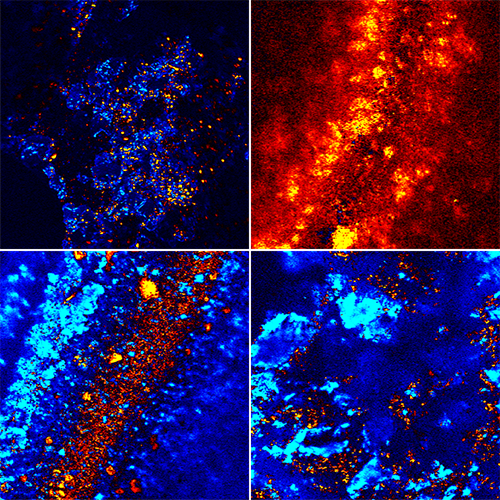

A field of 10-nanometer diameter silver nanoparticles (blue points) and clusters of 2-4 nanoparticles (other colored points) viewed under a dark-field hyperspectral microscope. The clear orbs are cells of live chlorella vulgaris algae. Image courtesy Nick Geitner.

Turner and Harris, New Zealand natives, have traveled halfway across the globe to meet with researchers at the Center for the Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (CEINT). Here, they are learning all they can about nanoparticles: how scientists go about detecting these unimaginably small objects, and how these tiny bits of matter interact with humans, with the environment and with each other.

The mesocosms, tucked deep in the Duke Forest, currently lay dormant.

The team hopes the insights they gather will inform the next phases of Steep, an ongoing project with science communicator Maryse de la Giroday which uses visual imagery to explore how humans interact with and “sense” the nanoparticles that are increasingly being used in our electronics, food, medicines, and even clothing.

“The general public, including ourselves, we don’t know anything about nanoparticles. We don’t understand them, we don’t know how to sense them, we don’t know where they are,” Turner said. “What we are trying to do is see how scientists sense nanoparticles, how they take data about them and translate it into sensory data.”

Duke Professor and CEINT member Mark Wiesner, who is Geitner’s postdoctoral advisor, serves as a scientific advisor on the project.

“Imagery is a challenge when talking about something that is too small to see,” Wiesner said. “Our mesocosm work provides an opportunity to visualize how were are investigating the interactions of nanomaterials with living systems, and our microscopy work provides some useful, if not beautiful images. But Raewyn has been brilliant in finding metaphors, cultural references, and accompanying images to get points across.”

Graduate student Amalia Turner describes how she uses the dark-field microscope to characterize gold nanoparticles in soil. From left: Amalia Turner, Nick Geitner, Raewyn Turner, and Brian Harris.

On Tuesday, Geitner led the pair on a soggy tour of the mesocosms, 30 miniature coastal ecosystems tucked into the Duke Forest where researchers are finding out where nanoparticles go when released into the environment. After that, the group retreated to the relative warmth of the laboratory to peek at the particles under a microscope.

Even at 400 times magnification, the silver nanoparticles on the slide can’t really be “seen” in any detail, Geitner explained.

“It is sort of like looking at the stars,” Geitner said. “You can’t tell what is a big star and what is a small star because they are so far away, you just get that point of light.”

But the image still contains loads of information, Geitner added, because each particle scatters a different color of light depending on its size and shape: particles on their own shine a cool blue, while particles that have joined together in clusters appear green, orange or red.

During the week, Harris and Turner saw a number of other techniques for studying nanoparticles, including scanning electron microscopes and molecular dynamics simulations.

An image from the Steep collection, which uses visual imagery to explore how humans interact with the increasingly abundant gold nanoparticles in our environment. Credit: Raewyn Turner and Brian Harris.

“What we have found really, really interesting is that the nanoparticles have different properties,” Turner said. “Each type of nanoparticle is different to each other one, and it also depends on which environment you put them into, just like how a human will behave in different environments in different ways.”

Geitner says the experience has been illuminating for him, too. “I have never in my life thought of nanoparticles from this perspective before,” Geitner said. “A lot of their questions are about really, what is the difference when you get down to atoms, molecules, nanoparticles? They are all really, really small, but what does small mean?”

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Amanda Cox

Post by Amanda Cox