In the second installment of our Film Diary series, Olivia uses Apostle (2018) as a vantage point for a deep dive into horror and fear, as well as how they intersect in media properties like film and video games.

With the very real fear of the 2020 election passing on, I now feel secure enough to enjoy a proper spookfest, the likes of which are typically reserved for October. I love horror films, so I’ve spent a little while pondering fear. Much of the discomfort associated with the emotion stems from the unknown: not a fear of the dark itself, but of our mysterious urge to discover what lies within it. Our fear response is far more entwined with fascination than we are comfortable with—it is this siren’s call which compounds our building dread when viewing a horror movie.

To fully appreciate the influence of horror media and our relationship with fear, it’s worth considering how the imagery of these films operates in association with other media, namely video games. Luckily my dutiful scrolling through Netflix led me to a proper case study: a 2018 horror film entitled Apostle. No worries, though one plot point will be vaguely described, this discussion is spoilers free.

Thomas Richardson (Dan Stevens)

Apostle is a blood soaked period piece with a certain heir of gothic mystery—both written and directed by Gareth Evans. The film stars Dan Stevens as one Thomas Richardson, a drifter set off on a perilous mission to save his sister from an island cult. Stevens’ grounded confidence makes for an impressive performance, and filtering the movie’s fraught atmosphere through the lens of a man stripped of his faith provides an added sense of dread.

Off the top, the record should reflect that I in no way present this film as any form of a cinematic masterpiece. Though bold, its themes leave little cohesion to work with, forcing any concrete reading of the film to remain elusive. That said, Apostle is not so much thoughtless as suffering from a mild cognitive dissonance. The film certainly has much to offer in terms of atmosphere, with Evans augmenting his action focused roots to opt for a steadier build—edging the story ever closer towards the dreary descent into madness.

Ultimately, Apostle feels like an equivocal conglomerate of horror aesthetics pieced into a single narrative—and yes, I mean that as a compliment. The plot is rather simplistic, but the film doesn’t necessarily suffer from it. What Evans lacks in finesse, he makes up for in evocative imagery. Apostle is dripping with style; its crisp and thoughtful cinematography gives the movie an aesthetic boost. It somehow manages to pull off the oxymoron that is artful gore. The tonal imagery of the film helps us understand two things about horror: it is neither wholly external nor wholly direct. Instead, horror is often internal and associative.

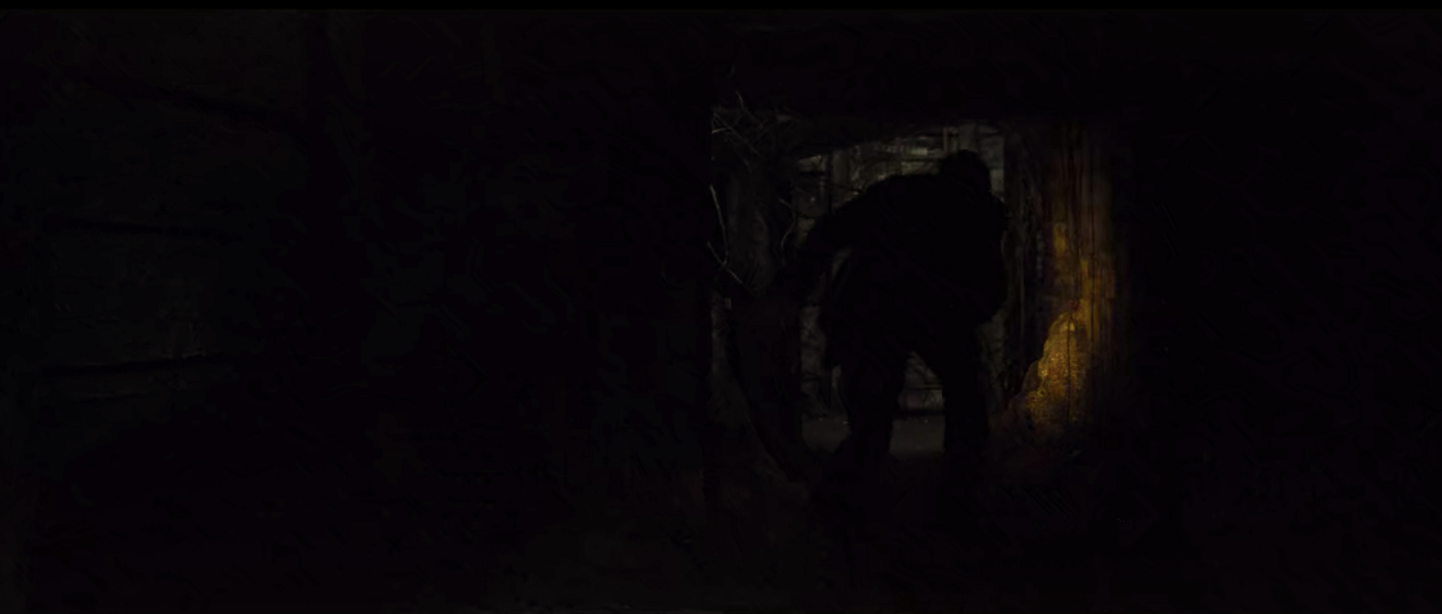

The primary image we’ll consider here begs comparison to one horror game in particular: Amnesia: The Dark Descent. About midway through Apostle, our protagonist finds himself in an underground passage, armed only with the shallow light of his lantern as he avoids a distant pursuer down the passage of dank stone and wood beams. Richardson is backlit with a faint warm light—silhouette creeping away from the camera. Decontextualized, the image is fairly innocuous. Yet, my response was anything but—almost metaphysical in its might.

Gameplay footage from Amnesia: The Dark Descent (2007)

Amnesia follows the first-person perspective of another Englishman, an amnesiac named Daniel, who awakens in a mysterious and abandoned castle. As Daniel, you, the player, traverse the layered and cavernous depths of Brennenberg castle—unarmed in your descent just like Apostle’s Richardson — all the while pursued by the mysterious and malevolent “Shadow.”

There are many surface-level similarities in the aforementioned situations, but these aren’t what drew my attention. Games are inherently interactive, and a large part of what shaped my experience playing Amnesia was a mechanic called the sanity meter. Players must avoid remaining in dark spaces or looking at harrowing phenomena for too long, lest their sanity drain. The game mechanics beg the question of the sanity of our endeavor, both in and outside of the game, or film, for our purposes. Both within and without, progression is illogical; it means certain death for the character and terror for the players or viewers. Yet, progression seems the only option, for only by answering the siren calls of the dark can you know the root of the thing within yourself—the thing drawing you forward. It speaks to a self-destructive streak, the uncomfortably human tendency to seek meaning in the descent, meaning whose lure pushes you onward past the point of logic.

This entire extrasensory association came from a single image, for horrific images speak to us. Horror films continue to fascinate and confound us because they are intimate. Apostle features a number of clever or more demonstrative images, but the subtlety of this tunnel shot (above) best illustrates my point. It is a testament to the sheer power of visual media that an almost primal fear response can be almost entirely unrelated to the intended artifice of the filmmaker; the work essentially speaks for itself, in conversation with each of its viewers and their experiences.

We tend to condescend the characters in horror stories, supposing the threat posed in their circumstances would be somehow rectified or circumvented with our rational intellect were we in their shoes. Yet this conviction is itself a mere phantasm. Our dark enchantment with visual horror mirrors the actions of the very characters at which we scoff. Despite knowing a film or game may terrify us, we persist in viewing and playing as if we as an audience are experiencing some collective call of the void. During scenes of high tension or gore, our eyes do not leave the screen. Even when they do, our gazes quickly draw themselves back.

Another common thread throughout horror stories is the search for existential meaning; for example, Daniel’s search for his memories and his sense of personal meaning throughout his descent in Amnesia. Irrational as it is, we press on through narratives that either jolt us with jumpscares or thematically disturb us for similar reasons. We must see how the story ends and find some meaning in the events.

Worse than these characters even, the knowledge we seek is often trite in comparison to their existential journeys. The average viewer is usually satiated with the revelation of basic story lore. We’re fascinated with the tale behind the horror. The prospect of being drawn to the feeling attached to the discovery of said tale — in Amnesia’s case, being forcibly passed down the gullet of some gaping unknowable thing as you willingly venture further down — scares us. It certainly scares me. Irrationality is what we fear. We are horrified not only by the breadth of the unknown in this world but also by the extent to which we are fascinated by it.

The Evil Within (2014)

For those truly curious about Apostle’s aesthetic ties to horror games, I’ll detail a few other parallels. Evans’ polished approach to action lends the film an adventurous aspect similar to The Evil Within, a charming Bethesda game whose themes are underlined quite nicely in its title. The film’s eerie pastoral setting is supplemented by expansive woods, whose dense and towering thickets make it seem a living, breathing entity à la Acid Wizard Studios’ survival horror phenomenon Darkwood. If you’re fascinated by adventure, gore, or an encroaching sense of inevitable disaster, this movie may be for you.

Apostle (2018) Dan Stevens. CR: Netflix

Remaining attentive to my responses to Apostle’s imagery certainly enhanced my viewing of the film. I have no doubt the same can be done for other movies and persons. I invite you to sit down with a horror film and explore your associations. It doesn’t have to be Apostle. Explore a few synopses or trailers and pick a film that interests you. Images facilitate introspection, which I find is best performed alone. After all, the midday sun can always compensate for the heightened state of isolation. Whatever the case, both good and bad horror movies can be the perfect fuel for your own personal spooky season.

Recent Comments