DTH Wideman Davis New Work – PAST-CARRY-FORWARD an original ballet created for the Dance Theatre of Harlem premiering october 2013

Information about the Production of past-carry-forward

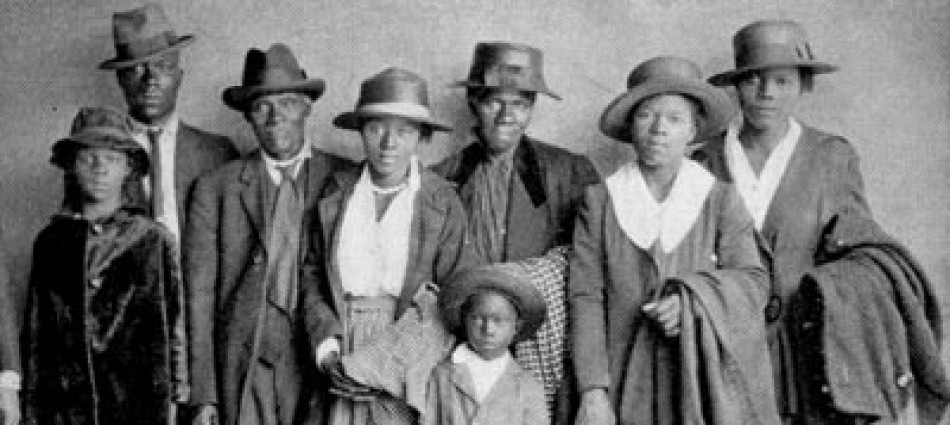

Tanya Wideman and Thaddeus Davis began this work as a way to consider the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance, a dynamic cultural movement that shaped African American participation in world culture in the 1920s. Wideman and Davis conceived the work as an exploration of the concept of “double consciousness,” a philosophical idea proffered by leading African American intellectual W.E.B. Dubois. DuBois wondered at the necessity of African Americans to live behind the “veil” of racial separation, to strive forth as both black and American, with those often contradictory political identities.

The choreography for past-carry-forward developed from research on the Great Migration of African Americans from the agrarian South to the industrial urban North in the early part of the twentieth-century. The migration forced many young African Americans into difficult situations, making choices to leave family at home in South while they searched for the promise of a better life – with more pay – in the North. The migration also lent energy to the Harlem Renaissance, and civil rights activism of the time. African American presence in a segregated military, working in the segregated service industry as Pullman railroad porters, and the presence of African Americans as entertainers to white American audiences are also considered in the work.

The work ends with an extended section of abstract movement that wonders at what we all carry forward from our understandings of our shared pasts. If the “veil” of racism could be lifted – in the 1920s, and maybe even in 2013 – what intimate truths could we learn about each other and the magnificent offerings of our creative humanity?

Scene Synopses

Migration One

The ballet begins with two Southern African Americans considering a move in the 1920s. The man and woman see each other as if in a mirror image, but each with a distinctive personality. As they hear the train whistle, they decide to move North to seek the promise of a better life. Taking their suitcases, which hold all of their worldly possessions, they move to New York City.

The Party

The Harlem Renaissance was sometimes thought of as a party that wouldn’t stop. Freed from the social constraints of the oppressively-segregated “Jim Crow” South, many African Americans in the urban North enjoyed nightlife without seeming end. The party had its limits though, and some Harlemites inevitably overdid things.

Migration Two

In an interlude, one of the Southern migrants of the first scene connects to an overly-manic Harlem party woman. The women share memories of their migration from the South, as well as the memory of their male relative’s service in the segregated military of the Great War, World War One.

Military Sequence

The male Southern migrant remembers his service in the segregated military of the Great War. Like many African Americans, he was conflicted as a black person and an American living in a country that regularly denied his humanity. His service in the military did not guarantee civil rights when he returned to the United States.

Migration Three

In an interlude, the men of the military pose for a photograph, as do the women in a Harlem nightclub revue.

Nightclub Sequence

Dancing in a Harlem nightclub allowed African American performers a professional outlet, even if their work was often monitored by white club owners and, of course, a white audience. In this sequence, two of the women performers enjoy a moment of each other’s company even as they perform a “cane dance,” popular in some acts of the 1920s.

Porter Sequence

Working as a Pullman Porter allowed some African American men a stable professional occupation that included travel; in the 1920s, the Pullman Company was the largest single employer of African American men. While the work was steady, the conditions were degrading and the porters were grossly underpaid. In this sequence, a porter considers his duties and responsibilities, as he imagines his life before he migrated North.

Abstract Sequence

past-carry-forward wonders at the connections between life of the Harlem Renaissance era and life for African Americans in 2013. In this sequence, the historical Pullman Porter invites the past to consider its own future. The characters from the historical sequences shed their costumes of the “Roaring 1920s” to meet each other in a space without racial segregation and oppression – a space of enlivened dance. Here, the dancers become twenty-first century people meeting and connecting with each other, remembering their shared and divergent histories, and wondering at their shared humanity.

Coda

In a powerful and emotional coda, two dancers consider the legacies of African American migration and twenty-first century life. Are they descendants of the migrants from the beginning of the work? What do they remember of that great movement from the rural South to the urban North? And what do they imagine for themselves, and each other, as they work through their memories and hopes for the future?