Home » Posts tagged 'black women'

Tag Archives: black women

Local Black Women Artists join Professor Neal for Ruby Fridays

Three black women artists, members of the vibrant and supportive Durham arts community, shared details of their creative practices, and the challenges and joys of being working artists at a Nov. 15 “Ruby Fridays” event.

Three black women artists, members of the vibrant and supportive Durham arts community, shared details of their creative practices, and the challenges and joys of being working artists at a Nov. 15 “Ruby Fridays” event.

Durham-based visual artists Candy Carver and Natasha Powell Walker, and independent filmmaker Natalie Bullock Brown joined Mark Anthony Neal, the James B. Duke Professor of African & African American Studies, for a lunchtime public conversation in the Ruby Lounge at the Rubenstein Arts Center.

The event was held in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the Department of African & African American Studies.

On being a working artist and having “day jobs”:

WALKER: I just got comfortable telling people at my nonprofit “day job” that I’m an artist. It’s easier at a nonprofit where people have lives. It’s been interesting to see how much they intersect, my “day job” and my art.

BROWN: My parents were supportive. They said make sure you get an advanced degree. I had worked on the Ken Burns Jazz series. I was really worried at age 27 that if I didn’t get married soon, I would not have kids. I left New York and moved here. I now have 2 children and I am married. I just got back to filmmaking about 6 years ago. I started teaching, mostly because I had flexibility with my schedule.

Every waking moment is teaching, filmmaking, kids. It’s challenging.

The funding part, in N.C., I have not figured that out yet. I’m 6 years into a project that I could have done in 3 years in New York.

CARVER: I don’t have a 9-to-5 but I work all the time. It’s fun.

I actually work more than 9-to-5. It’s more than a full-time job, if we’re talking about 40 hours a week. My job can travel with me. I have a lot more flexibility than a 9-to-5. I’m currently figuring out balance, and opportunities that won’t cost me time. I need to be happy to make good work, unlike Mary J. Blige.

On the challenges of being an artist in the Triangle area:

On the challenges of being an artist in the Triangle area:

CARVER: There’s a challenge that many of the art galleries are run by white women and that’s a particular perspective that they are choosing art from.

As our area becomes more diverse they will have to seek from a more diverse spectrum of creativity. Black life is way more interesting than shackles, chains and lunch counters. It’s more interesting and it’s broader.

On being taken seriously as women:

WALKER: I’ve experienced harassment. I’ve had both male and female mentors tell me to use it to my advantage, or that’s just the way it is.

CARVER: The majority of my clients are men. Why? I would have thought it would be more women. I’m not sure why. But I’m comfortable with guys. Always have been.

BROWN: Women don’t get as much funding as men. You might have to work on projects where you’re token, or the topic is black and you’re being used for your blackness.

It doesn’t matter if you went to film school. What matters is experience. I want the chance to do artwork that will help me to grow.

On where they create:

WALKER: I like creating at home. I don’t like people walking up to me while I’m creating. I had a studio space in Richmond that I shared.

CARVER: The whole downstairs of my house is an art studio. My dining room and living room are full of art supplies. I’m social, dialoguing doesn’t disrupt me too much. I actually enjoy it. I paint on the floor. It feels nice. I’ve painted on the walls. My mother learned pretty early that I was a different kind of kid.

What will you be doing 5 years from now?

CARVER: That’s so limiting. If I had done what I thought 5 years ago I would have missed out on so much.

I’m working on figuring out ways to make more money and work less.

On “black girl magic”:

CARVER: It’s the ability to pivot, to constantly and successfully adjust.

BROWN: It agree that it is being able to react in the moment to what is needed. It’s being able to have joy in the midst of all of the challenges. Also, it has begun to encapsulate this idea of being a superwoman, which is not real, not healthy, not sustainable.

Magic has be paid, funded, supported or it will fizzle.

Co-Creating Knowledge: An Intellectual Reunion of Duke Alumnae

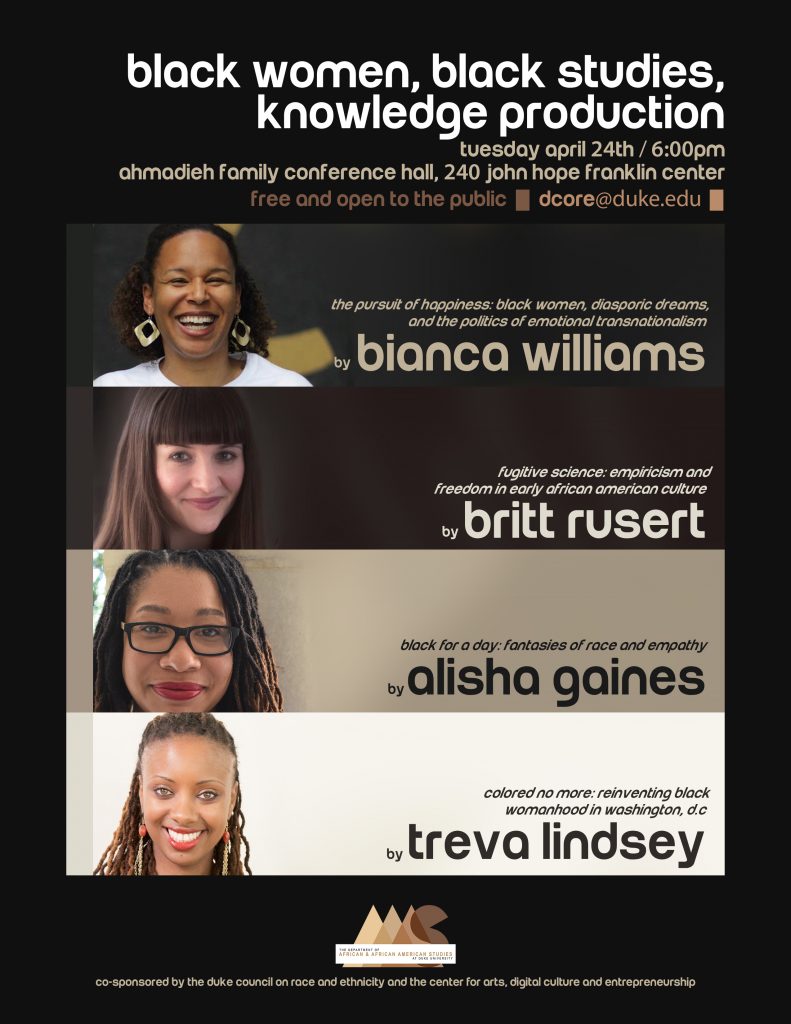

More than 50 people gathered in the Ahmadieh Family Conference Room on Tuesday evening, April 24, for a special meeting of Duke’s Introduction to African & African American Studies class, taught this spring by department chair Mark Anthony Neal.

Professors Britt Rusert, Treva Lindsey, Alisha Gaines and Bianca Williams are Duke Ph.D.’s who each had a book on blackness published in the past year. Neal made those books assigned reading for the spring class and invited the alumnae back to campus to speak with students and to revisit their formative years where the seeds for their intellectual pursuits were planted.

The symposium, “Black Women, Black Studies, Knowledge Production,” was entirely curated by graduate and undergraduate students in a demonstration of vertical learning. English Ph.D. student and teaching assistant Israel Durham designed the program for the 2.5 hour symposium, allowing each student an opportunity to converse with the authors.

The students, divided into small groups, passed a microphone and peppered each alumna with thoughtful questions related to their research as well as their scholarly approach and process. View Photos

Wearing a “#CiteBlackWomen” t-shirt, Williams told students that what they were experiencing was special and a testament to the “brilliant teaching” at Duke.

“You get to co-create. You also know things. You have useful questions. You know enough to engage scholars,” she told students.

“I just want you to know this isn’t normal. This doesn’t usually happen,” Williams said, noting the generosity of professors like Neal and Wahneema Lubiano, an associate professor and mentor to the women, who also attended and joined the women for the last panel of the evening.

“Wahneema would write down every foolish thing we said,” Williams remembered of her time as a student. “It might not have been what I said, but [she knew] what I meant. She would take our nugget, add to it, and give it back… That is generosity and it’s not the norm. After being in other environments, I want you to know this is a gift that we all received.”

Lindsey agreed, reminiscing about the familial kinship she felt in her cohort and with the faculty.

“The faculty believed in us as knowledge producers,” Lindsey said. “I wouldn’t have made it without Wahneema and MAN because of the confidence they instilled in us to be voices, but also to be on the front lines when things went down here,” Lindsey said. “That is the type of faculty member I want to be.”

Gaines, who is interested in black popular culture and reality television, said Black women gave her a way to imagine herself as a scholar and a thinker, especially as an undergraduate student at Spelman.

“I’m a good teacher because I have had good models for it,” Gaines said.

Rusert remembers the freedom to be intellectually adventurous while she was a student at Duke.

“I was 22 years old and remember being in that class (The Post-Black Aesthetic). MAN took our ideas seriously. I remember being like ‘wow!’ This professor really wants to hear what I think,” she said, adding that the interdisciplinarity of the department prepared her for study in her field in unexpected ways.

“I was 22 years old and remember being in that class (The Post-Black Aesthetic). MAN took our ideas seriously. I remember being like ‘wow!’ This professor really wants to hear what I think,” she said, adding that the interdisciplinarity of the department prepared her for study in her field in unexpected ways.

Also, she said that she’s been able to confront Southern bias as a professor now teaching in New England.

“I am really grateful to have had time training in the South because I can correct some misunderstandings,” Rusert said.

Rusert is an assistant professor in the W. E. B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at University of Massachusetts, Amherst, is the author of Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture and co-editor of W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America, a collection of data visualizations Du Bois contributed to the 1900 Paris Exposition and forthcoming from Princeton Architectural Press in fall 2018. She earned an English Ph.D. and certificate in feminist studies from Duke in 2009. She is beginning a new monograph about William J. Wilson’s African-American Picture Gallery (1859), a text that imagines the first museum of black art in the United States.

Lindsey is an associate professor and the Director of Undergraduate Studies of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Ohio State University. She authored, Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington D.C., a Choice 2017 “Outstanding Academic Title.” Recently dubbed #ProfessorBae by Bossip magazine, Lindsey’s research and teaching interests include African American women’s history, black popular and expressive culture, black feminism(s), hip hop studies, critical race and gender theory, and sexual politics. She earned a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in history at Duke.

A lifelong Michael Jackson fan, Alisha Gaines received a Ph.D. in English from Duke and also received the graduate certificate in African and African American Studies. She is assistant professor of English at Florida State University where she won a university-wide Undergraduate Teaching Award in 2017. Her first book, Black for a Day: Fantasies of Race and Empathy, was published in Spring 2017. Inspired by the short-lived F/X reality tv show “Black.White,” the book constructs a genealogy of white liberals who temporarily “become” black under the alibi of racial empathy. As such, Gaines has a love/hate relationship with Rachel Dolezal.

An associate professor of anthropology at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, Bianca Williams is also Black Lives Matter organizer, co-founding the Denver chapter. She earned a bachelor’s degree and a Ph.D. in cultural anthropology at Duke, and a graduate certificate in African and African American Studies. Her book, The Pursuit of Happiness: Black Women, Diasporic Dreams, and the Politics of Emotional Transnationalism, how African-American women use international travel and the Internet as tools for pursuing happiness and leisure; creating diasporic relationships; and critiquing American racism and sexism. Central to her research is the question, how do Black women develop strategies for enduring and resisting the effects of racism and sexism, while attempting to maintain emotional wellness?

Neal, host of weekly webcast Left of Black, interviewed the four women about their work earlier that day in the John Hope Franklin Center studio for upcoming episodes of the show. An appearance on Left of Black has increasingly become a rite of passage for a network of young black studies scholars.

“A cohort experience becomes part of our building of knowledge so the production part is apparent. We’re making it as craft, it’s not an arcane thing,” Lubiano, an associate professor of literature and a long-time Duke faculty member, told students at the symposium. “We are actively participating in creating knowledge, thinking about the students and making them central to the work early on.

“I’ve seen students go from undergrad to full professorships,” she said. “Making knowledge is not a finished ‘house,’ we’re always building. It’s important to make your fracturing speak to someone else’s fracturing. We take seriously the process of remaking knowledge.”

‘Don’t Get It Twisted:’ Black Girls’ Dehumanization Is Not the Same as Adultification

by Linda M. Burton & PhD & Donna-Marie Winn, Ph.D.

Ask NBC News. They recently learned what happens when you tweet a story with a headline that erroneously twisted Sally Hemmings’ personal narrative of horrific, repeated rapes at the hands of Thomas Jefferson into a headline about her being Jefferson’s mistress. NBC News learned that in this current climate of close interrogation of history and fact-checking, Twitter, especially Black Twitter, claps back. Mightily.

NBC News now knows not to twist, at least one Black woman’s narrative, Sally Hemmings’, into something it was not. But what about the rest of American society? Do pockets of America continue to twist Black girls’ narratives about who they are and their vulnerability and innocence into tales of willing and complicit precocious sexuality?

In the recently released report, “Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood,” authored by Rebecca Epstein, Jamilia J. Black, and Thalia Gonzalez, this question is answered with a resounding, “YES!” This report calls into sharp focus adults’ perceptions that dehumanize and both explicitly and implicitly impugn Black girls. The report finds that adult respondents from their study perceive Black girls as young as five to nine years old, in contrast to white girls, as needing less nurturance, protection, support, and comfort, while at the same time being more independent and knowing more about adult topics and sex.

To their credit, the authors chronicle the history of such dehumanization of Black girls and Black boys back to America’s inception and lift up the institution of slavery as further proof that such perceptions are not new. Such dehumanizing perceptions are often used to retell and revise the terror inflicted upon and objectification of Black bodies throughout American history.

Additionally, Epstein, Black, and Gonzalez review several dominant paradigms about Black femininity that emerged during slavery and note that the contemporary manifestations of these paradigms belie the implicit biases and racism (our word not theirs) that result in Black girls being treated more harshly and their developmental behaviors being criminalized.

We agree with the authors’ point about the continued, undeserved dehumanization of Black girls. Unfortunately, while the Girlhood Interrupted report focuses the spotlight on these dehumanizing perceptions of Black girls, the report also equates such perceptions with the term adultification.

As Black female behavioral scientists who have cumulatively studied adultification in the lives of Black girls and boys (see Burton, Winn, Stevenson, & McKinney, 2015) and Black families in different settings for over 50 years, we are concerned that framing the dehumanization of Black girls identified in the report as adultification is deeply problematic. In fact, we disagree altogether with the choice of adultification as a way to situate this very important discourse.

Admittedly, the authors, as a few other authors have done before them, defined adultification as, “a social or cultural stereotype that is based on how adults perceive children in the absence of knowledge of children’s behavior and verbalizations.” And from there they argue that their participants’ perceptions of Black girls as being less innocent and in need of less nurturance, guidance, and protection are similar to the dehumanizing stereotypes of Black women.

Using the adultification concept in this way twists the fundamental meaning and incumbent processes as it is discussed in existing social science and family therapy literature. In a 2007 article, Burton provides a standard definition of adultification that is not dehumanizing: “adultification comprises contextual, social, and developmental processes in which youth are prematurely, and often inappropriately, exposed to adult knowledge and assume extensive adult roles and responsibilities within their family network.”

Several of the Epstein, Black, and Gonzalez interview questions directly interrogate adults’ perceptions about parameters of the adultification process, for example: “How often do Black (or white) females take on adult responsibilities? How knowledgeable are Black (or white) females about sex?” As asked of respondents, however, even the second question is likely to conflate potentially precocious knowledge about sex with Black female children’s developmentally appropriate knowledge about sexual reproduction resulting from healthy, proactive parent-child conversations in response to the earlier onset of puberty for Black girls.

The other questions asked in the study have nothing to do with adultification. Quite the contrary, clinically, children who take on these roles need a lot of nurturance, comfort, and support to adequately learn and perform such roles. Playing an adult in a child’s body, with a child’s emotional maturity is hard. Full Stop. Black women need nurturance, comfort, and support too. Fuller Stop. In our view, the frame of adultification, in the ways Epstein, Black, and Gonzalez define it, seems to be more accurately and simply be characterized as dehumanization and promoting racist gendered stereotypes about Black females.

To be clear, Black girls’ being more knowledgeable about sex, perhaps sexual reproduction, at earlier ages than white girls does not equate with any definition of what being a Black woman is to us and many others. Furthermore, twisted perceptions about Black girls’ knowledge of sexual risks conjuring up the age-old, American stereotypes of the “jezebel” Black woman which, as Epstein, Black, and Gonzalez note, persist in present day American culture. That stereotype promotes racist notions of Black women as precociously sexualized, morally bankrupt, incapable of regulating their emotions, and unable to deeply feel — loss, love, grief or much of anything else for that matter.

We agree that adult Black women are still considered in the context of this racist, humanity eroding, gender offensive trope. And, we are concerned that viewing little Black girls through the Black female adultification lens, as posited by Epstein, Black, and Gonzalez, risks further imposing such dehumanizing stereotypes onto lives of Black children.

Indeed, conflating adultification with dehumanizing perspectives is intellectually flawed and poses obstacles in discerning alternative framings of what is happening in the lives of young Black girls and how the broader population is complicit in the process. Rather than considering the adult respondents’ perceptions that Black girls behave in adultified ways, shouldn’t we call it what it really is?

There are generic processes that people engage in on a daily basis to reproduce race and gender inequalities among individuals and groups. One such process is emotion management. Because race and gender inequalities foment feelings such as anger, resentment, despair, and sympathy that threaten to destabilize the social order, these emotions must be managed, which means, relative to the study we discuss here, that our perceptions and emotions about Black girls “must be managed.”

One way of managing societal emotions is by regulating the narrative about Black girls using particular language and assigning certain attributes to them. The dominant group in society usually controls the narrative and reinforces it in existing social structures, in this case schools and the judicial system, while more private discourses among ordinary people work to strengthen destructive narratives and stereotypes. Indeed, emotion management by controlling negative narratives on Blacks is thriving in certain pockets in today’s America.

As Black female behavioral scientists whose humanist resolve and intellectual rigor was birthed in the complex cities of Compton, California and New Orleans, Louisiana, respectively, we have lived experiences about the damage that twisted narratives and errant frames can visit upon Black and white America, particularly when scientists waywardly compare Blacks to whites. Such twisted frames attempt to strip us Blacks of our humanity and seek to render us as less than or an oddity in that, regardless of gender or class, we are perceived as having no sense of emotional intelligence, proclivity to care for others, or ability to self-regulate, regardless of our ages. Such framings move us no closer to accurately identifying fundamental causes in the persistent strengths inherent in or inequalities hoisted upon Blacks in America for centuries. Less we forget . . . Black women have shown America how to be humane.

We hope that the Girlhood Interrupted report can spark a wider discussion on the uncertainty that some Black girls live with on a daily basis, particularly those Black girls whose families and/or communities are economically impoverished or unsafe. Uncertainty is a state of ambiguity, one in which immediate and future conditions or events are unpredictable or otherwise not clearly determinable by those involved. In some environments, uncertainty, even when buttressed by community strengths and individual connections, can lead to a narrowing of viable options, a hesitancy to act, and a diminished likelihood of acting in ways that support longer-term, positive outcomes.

Under such uncertain conditions, some girls may act with an eye toward the moment because unpredictable resources and the ever-present specter of need require orientation to the here and now. This behavior often emerges from a lack of control girls may experience as they struggle to simply survive in a world where key resources are scarce, there are limited opportunities to thrive, and a broader society dehumanizes them in narratives based on erroneous assumptions and interpretations of their lived experiences.

Untwisting this narrative by, in this instance, uncoupling the frame of adultification and dehumanization is particularly important given the context of recent political rhetoric in America. It has become fairly common for public and political discourses concerning people of color and their communities to be inappropriately cast as having undesirable attributes.

In today’s America, we seem to have once again backslid to the days of the Moynihan Report where national leaders promulgated stereotypes about Black families being “tangles of pathology” and dysfunctional, no matter their social class. As in times past, national leaders foment the wholesale acceptance of such denigrating stereotypes among their followers who have little to no understanding of the profound inaccuracies of the rhetoric and who exercise little discretion or censorship.

We optimistically ask America not to get the findings in this report twisted. The adult perceptions studied in this work reflect the dehumanization of Black girls, not their adultification into Black women. Does America have the capacity to resist the twist, censuring and holding itself accountable for creating accurate narratives, frames, and discourses about Black girls and the Black women they aspire to become? If not, let NBC News’ recent twist serve as a good example of a bad example. There will be a clap back.

Linda M. Burton, Ph.D., is Dean of Social Sciences, Director of the Center for Child and Family Policy and the James B. Duke Professor of Sociology, and a professor of public policy at Duke University. Donna-Marie Winn, Ph.D., is a Senior Research Associate for the Kenan Institute for Private Enterprise at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.