Alexandra Angelova was 16 when she began experiencing blurry vision and occasional dizzy spells. Instead of going away, her symptoms gradually grew worse. Now nearly a decade later, with her vision at one percent of its original strength and with balance problems that prevent standing or walking unassisted, these symptoms inform every aspect of her daily life.

Alexandra Angelova was 16 when she began experiencing blurry vision and occasional dizzy spells. Instead of going away, her symptoms gradually grew worse. Now nearly a decade later, with her vision at one percent of its original strength and with balance problems that prevent standing or walking unassisted, these symptoms inform every aspect of her daily life.

Angelova gets around the house and walks her dog, Sunny, using a rollator, or seated walker. She presses her back against the wall for balance when going up and down stairs. Every item in her house has a set location so she can find it with her limited vision.

“I cannot perform many basic things which are normal for a healthy person,” Angelova said. “I have to plan every movement and how to do it–how to hold a fork, how to take a shower, and so on.”

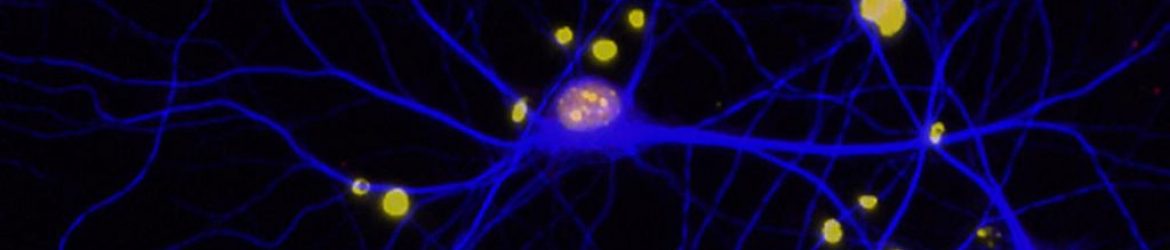

Angelova’s case is typical for people with spinocerebellar ataxia type 7, or SCA7, a chronic, inherited neurodegenerative disease. A child with a parent with SCA7 has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the condition. It is caused by a genetic mutation which causes the body to produce a malformed, toxic version of a normally healthy protein.

People with SCA7 develop normally as children when the body has the ability to filter out these malformed proteins. But sometime during adolescence or adulthood this protective effect disappears. Without it, the malformed proteins destroy cells in the retinas and the cerebellum, the brain’s balance center, taking sight and coordination with them.

Symptoms of SCA7 gradually worsen over time, and there is no cure. Angelova has had to make a series of lifestyle adjustments to compensate. Her eyesight recently deteriorated to the point where she can no longer read books, so she has switched to audiobooks. Adjusting the display of her smartphone to heighten contrast and magnify words and images has allowed Angelova to communicate with family and the outside world.

She works to be as independent as possible, doing her own laundry, cleaning, and shopping, and other tasks, but it’s difficult.

“I insist on doing these things, because it makes me independent and I face these challenges with pleasure,” Angelova says.

Read the full story on Magnify, an online magazine from the Duke University School of Medicine.

Recent Comments