The Tom River

The Tom River

Chekhov’s trip to Sakhalin was cold, long, uncomfortable, dangerous, and, to judge from his reports from the road, mostly wet. At the end of the 19th century, Siberia’s roads were primarily rivers, running south-north; though the Trans-Siberian railway was glimmering in decision-makers’ minds, things would not get underway until a few years later. If you travel anywhere in Russia during the spring, you are going to get caught in the thaw; all that snow melts, leaving you sopping wet and helpless to get where you’re going. From the window of a speeding trans-Siberian train between Ulan-Ude and Khabarovsk, it’s beautiful…

though your (nice, quiet, female) kupe-mate Liza tells you that the serene, shimmery waterscape you’re seeing is actually the aftermath of a disastrous flood.

All of this inclines the mind to contemplation, musing, philosophizing, and complaining. In Chekhov’s case, some of this mental and verbal activity takes place at post stations (while waiting for horses, trying to dry off, and drinking tea). Some of it finds expression in his travel notes “From Siberia” and letters home, and some of it brews quietly inside, fermenting and mixing with impressions. This potent brew will gush forth when the big trip is over and when, for the first time in his life, Chekhov will settle down in a home of his own. How much the Melikhovo fictional masterpieces owe to this period of suffering and reflection cannot be calculated–but I’ll bet it’s more than we usually think. We may not notice because the references to Siberia in his subsequent fiction are muted and few. And of course the Island of Sakhalin, and The Island of Sakhalin, came in between the experience and the fiction.

Art is an alchemy that science, fortunately, cannot explain.

After his wet crossing of the Irtysh and that short interval with Sergei in Tiukalinsk, Chekhov pressed on through various small villages, including the appropriately named Pustynnoe (empty or desolate), BTW not stopping in nearby Omsk, where Sergei and I began. “Empty” may well characterize the annoyances of this leg of his trip, for he was held up by various absences (or post horses, of boats) on his way to the Tom River. Finally, after a difficult crossing, he made it to Tomsk late at night on May 15. He would spend a week here, leaving May 21 (yes, 1890, despite Sergei).

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

Chekhov wrote to his family from Tomsk on 20 May [the important bit is translated].

[…]

Два месяца тому назад умер здесь таганрогский таможенный Кузовлев, в нищете.

От нечего делать принялся за дорожные впечатления и посылаю их в «Новое время»; будете читать их приблизительно после 10 июня. Пишу обо всем понемножку: трень-брень. Пишу не для славы, а в отношении денег и в рассуждении взятого аванса.

[now here’s the snarky bit about Tomsk]

Томск скучнейший город. Если судить по тем пьяницам, с которыми я познакомился, и по тем вумным людям, которые приходили ко мне в номер на поклонение, то и люди здесь прескучнейшие. По крайней мере мне с ними так невесело, что я приказал человеку никого не принимать.

Tomsk is a colossally boring town. To judge from the drunks I met, and from the local eggheads who came to my hotel room to pay their respects, the people here are utterly stultifying. I had such an unpleasant time with them that I ordered the hotel servant not to receive anyone.

Был в бане. Отдавал в стирку белье (по 5 коп. за платок!). Покупал от скуки шоколат.

Благодарю Ивана за книги. Я теперь покоен. Если он не с вами, то напишите ему, что я кланяюсь. Отцу послано письмо. Послал бы таковое и Ивану, но не знаю наверное, где он живет и куда поехал.

Через 2½ дня буду в Красноярске, а через 7½ — 8 в Иркутске. До Иркутска 1500 верст.

Заварил себе кофе и сейчас буду пить. Утро. Скоро зазвонят к поздней обедне.

После Томска начнется тайга. Посмотрим.

[…] Ваш А. Чехов.

Душа моя кричит караул. Помилуйте, мой бедный чемодан-сундук остается в Томске, а покупаю я себе новый чемодан, мягкий и плоский, на к<ото>ром можно сидеть и к<ото>рый не разобьется от тряски. Бедный сундучок таким образом попал в Сибирь на поселение.

A brief nod to the Tomsk postal service here–how else would he have been able to get books from his brother Ivan? (and of course we are curious as to what books they were):

Usually only the nasty part about Tomsk in Chekhov’s letter is quoted, but zooming back provides a context. Exhausted from the road, Chekhov learns of the death of a home-town acquaintance here in Tomsk; annoyed at the cost of doing laundry

(The cost of doing laundry is one thing that I can attest has not changed in Russia hotels over the ensuing 129 years. Chekhov paid 5 kopecks for a hanky to be washed; today to wash the same item will cost you 50 rubles (which I’m going to guess is about the equivalent by 21st-century standards). Yes, you heard me right-almost a dollar. Your jeans will cost $6 to wash. You gasp, then ask yourself which is better: to spend the whole day stomping on your jeans in the shower or to go out questing for Chekhov during your brief time on Sakhalin Island. It took you several decades to get here, remember]. BTW if you are young and nimble enough to stay in hostels (aka dorm rooms with bunks for eight people and one flooded bathroom down the hall that you share with four other dorm rooms and some local fauna who have managed to crawl up all four flights of stairs, because the other bathroom is out of service [your Russian word of the day: na remont]), you can do an entire load of laundry for 150 rubles (less than you’ll pay in a US laundrymat). I have done this. But oh, the noise, oh, the lines, oh, the miasmas… To be fair, I don’t think they want a professor sleeping with them; it’s kind of a reversal of the Vakhta situation in the train kupe. I get it. And I won’t join you guys at Shooters either. Or Facebook you. Live these frisky years of your life free from prying eyes; they will end soon, and before you know it you will have a toddler lurking at your feet, soaking up everything you say and do with his shockingly sensitive radar.

aware of his debt to his dean, I mean Suvorin, and the consequent need to sit there in our hotel room and write; aware that he was not yet even halfway through his journey): it all just compounds the feelings of exhaustion and boredom he brought to Tomsk. It is from Tomsk that Chekhov sent his first travel notes from the road for publication in Suvorin’s New Time.

PSS Editors’ notes: In the first six chapters he sent from Tomsk, Chekhov did describe the segment of his trip between Tiumen and Tomsk, explaining in a letter to Suvorin that he was writing it for him personally, because he was not afraid of being “‘too subjective and not afraid thаt there were more thoughts and feelings in them about Chekhov than about Siberia.” (В первых шести главах, отправленных из Томска, Чехов все же осветил отрезок пути между Тюменью и Томском, оговорив в письме Суворину, что писал лично для него, потому не боялся быть «слишком субъективным и не боялся, что в них больше чеховских чувств и мыслей, чем Сибири»)

I don’t disagree with Chekhov all that often, but in 2019 he is dead wrong about Tomsk. My impressions are different. What I saw was a charming university town with a lovely riverfront promenade and stunning wooden architecture. I could picture living here–though admittedly you have to factor in that I hit town on a lovely warm summer day, and was welcomed by generous, solicitous hosts who showed me Tomsk’s best features. I saw no drunks (meaning, people who might have seemed drunk from the outside).

But really, Chekhov, if a visitor just passing through can draw sweeping conclusions about a whole town from the sighting of a few drunks in the street, how would the rest of us  fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk.

fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk.

Just saying.

But Tomsk is no dummy. The town would take sweet revenge in 2004. As part of its celebration of its 400th birthday (commemorated in part by the stone at your right, if you’re on a grown-up computer),  the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

eyeshot of The Slavyansky Bazaar, the writer’s dining place of choice in Tomsk. Predictably, Chekhov’s oversized feet and tipped vertical axis, along with other irreverent details provoked an indignant reaction from a small segment of pedantic Tomskian egg-heads. Chekhov would never have gone out barefooted! He is our great genius! How can you show such disrespect to our national heritage?

Oh, how I would love to win the lottery and fund a statue of Chekhov, author of “Fat and Thin,” “The Malefactor,” “Daughter of Albion,” and hundreds of other hilarious send-ups of human nature. My Chekhov would rolling (in laughter) in his grave, or perhaps in a pas de deux with the inebriated peasant. I would try to persuade the (any) town to place it next to some national hero presiding over the city’s central square amid all the government buildings. Why not bring some life, and laughter, and love, and joy, and dare we say, power, into the public square? The millions of kids gathering out there, upon whose thin, passionate shoulders rests the world’s terrifying future, sure could use it.

The statue in the center happens to be in Krasnoyarsk, but every Russian provincial town has one.

And don’t think you’re off the hook, USA.

I came upon the beautiful, funny horse, by extraordinary Buryat artist Bato Dashitsyrenov, a couple of weeks later (a few days ago) in Ulan-Ude’s central art museum, and I had to double him here for full effect. Most of the writers so urgently commemorated with their statues and street names and museums and plaques had lots and lots of bad days, many of them in the very cities where their statues stand in all their bronze dignity, intimidating the mortals who dare to approach with anything but a pure, blank heart and a bouquet of flowers. We have addressed this with Tolstoy in Kazan. And I’m sure more opportunities will arise. What is wrong with shaking things up a bit? They were people too, despite the divine spark they harbored within, which may be absent, or more likely suppressed, in your run-of-the-mill egg-head.

Really: why aren’t there more funny statues out there? (In this category, Omsk gets an honorable mention).

Speaking of calming down, ahem, fortunately Tanya (see below) gave me a little model of the Tomsk Chekhov statue, so I did not have

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

landmarks (hee hee hee), one can pound out a tune on a durable old piano placed out here on the Tom river bank. This, too, is an idea that every single town in the world should borrow, and not just during carefully curated arts weeks.

It’s OK, we don’t bite.

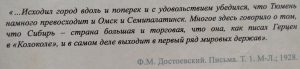

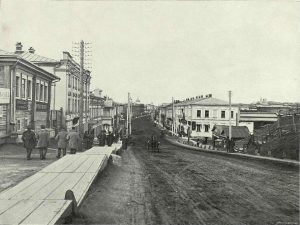

Anyway, if and when he left his hotel room, Chekhov might have seen something like this:

As, astonishingly, did I. What might have seemed dank and backward to a big-city traveler surfing through provincial tоwns in 1890, to me has the look of a world heritage site. And I beg UNESCO to come here and protect this incredible treasure: not just one of these houses, but the whole town.

In Tomsk, Dostoevsky, despite his absence, led me into the generous and alert scholarly care of good people, long-term Dostoevsky Campers, professors Elena Novikova and Olga Sedelnikova (both still glowing from their trip to this summer’s International Symposium in Boston). Translation (and Dostoevsky) also conjured up the very kind Tatyana (Tanya) Korotchenko, an acute and sensitive scholar of literature and translation, who once studied in the US, at the University of Wisconsin. Elena and Tanya showed me around the University and introduced me to some colleagues.

Olga and her beautiful white-furred assistant Nika treated me to a calm, but utterly fascinating drive round Tomsk’s wooden neighborhoods. One very nice thing about Olga is that she drives in the right lane, which soothes your nerves and allows you fully to concentrate on the wonders you are seeing around you.

Be sure not to miss the Burger Bar.

In “From Siberia,” Chekhov tells of a conversation he has with a peasant (Petr Petrovich) at Krasny Yar while enduring a long wait for a boat to arrive so he can continue his journey. In his folksy way, Petr Petrovich warns of the destruction the railroad will bring:

“Around here, if someone’s been as far as Tomsk, he sticks his nose in the air, like he’s been around the whole world and back. But the papers are saying that they’re going to bring the railroad here soon. Tell me, sir, what’s that going to be like? The machine runs on steam – I get that. But if it has to pass through the village, it’s going to break down the huts and run over people!” (Chapter V), May 13, 1890)

These stunning houses go on and on, and you can’t get enough, and you worry about them like babies, and you wonder if the fire prevention people are on the case, and you feel it’s time to petition UNESCO. And you wish that Chekhov had mentioned these cool wooden buildings, because if he had, people would have paid attention, maybe, and they would have been loved even more, and preserved even better, than they are now. But then you realize that probably everywhere Chekhov went he saw wooden houses like these, because they were a standard thing in Siberia, and the reason you don’t see so many nowadays is of course that wood burns, and rots, and is replaced by more durable, but less beautiful materials. And you remember that the trans-Siberian railroad passed Tomsk by, meaning that there was no incentive for people to gut the town and turn it into an industrial capital like other Siberian cities, with their noise, and pollution, and their spewings into the rivers, and their big roads built on the bones of dead, beautiful wooden buildings, wide asphalt roads cleared for trucks to speed along, delivering heavy things to the train station; streets lined with hulking, ugly concrete buildings to manufacture stuff in, and other buildings to sell that stuff in, and other buildings for workers to live in, and banks to put all that new money in. And all of it rushing to and from the railroad and taking Tomsk’s precious things away.

This phantom, apocalyptic place, railroaded Tomsk, exists only as a sideshadow, an alternative fate that could have befallen the town and swept its world treasures onto the trash heap, along with the spirits of its people. Thank you, Tomsk, for lying low and letting the fast things pass you by. But now that I think about it, the joke, here too, is on the rest of us.

Olga takes me up to the mountaintop, where a fortress was, where there are other streets lined with yet more, beautiful, wooden houses, and a church, and where you can look down over the city. And the Siberian clouds tell their story.

I think that the next person who travels this route should focus exclusively on the sky.

Everything is more exciting when you are with your kind, whatever species. But we are nowhere near finished. There is a whole lot more to see in Tomsk.

The University

It’s not really fair to call it “the” university, since there are lots of institutions of higher learning in Tomsk. But my visit happened to be at Tomsk State University, where Elena teaches, and where Tanya was in the graduate program before taking a position at the nearby Tomsk Polytechnic University. There are an awful lot of smart people in Tomsk, Siberia’s university town: formidable scholars, teachers, translators, researchers, and, of course students. The visitor can feel an abundance of human talent and energy here, a heady mix of youth, irreverence, studiousness, lightheartedness, and dedication to the work and business and mission of education.

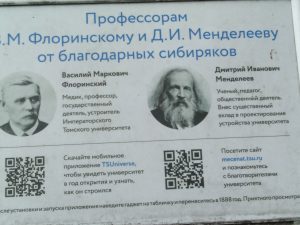

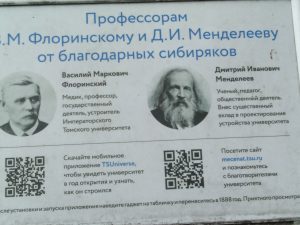

Tomsk State University is proud to be the first Russian University founded on Asian territory, opened, after much thinking and planning and building, in 1898.Elena and Tanya take me to see two founders of Tomsk University, Professors Florinsky and our old acquaintance from Tobolsk, Dmitry Mendeleev.

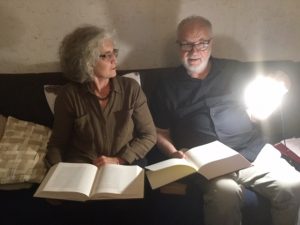

Elena (on the right), who is professor and doctor (which means a lot in Russia), teaches and researches in the department of Russian and Foreign Literature, and does a lot of outreach through the “Open University” project. Everyone in Russia is talking about ways to celebrate the upcoming big bicentennial of Dostoevsky’s birth, and a number of Siberian universities are going to hold conferences. Elena and Tanya and I meet the Dean of Philology, and there is some discussion of ways to celebrate the occasion virtually.

Tomsk State University is anchored by its stately white central building; here decision-makers work, and the hallways are lined with portraits of founders and famous professors. The room where important meetings are held doubles as a museum featuring artifacts from Siberian peoples.

,

,

We take a moment to admire the portrait of Faina Zinovievna Kanunova, revered philologist and professor and long-serving chair of the Russian and Foreign Literature Department who won the Russian state prize and many other honors. I take a minute to ponder how many American university professors ever give some thought to the contributions of their predecessors, who made their institutions what they are. Administrators do think about our workplace’s human history, amid all their other concerns, but do professors? It feels like a Russian thing to me.

In Tomsk I felt, as I had before in Kazan and Tobolsk, a kind of tangible human genealogy in the history of intellectual and educational life. These new names join those of Mendeleev and Florinsky, immortalized in the university courtyard, and serve as a kind of family line of which any of us who spend time studying, researching and teaching, can feel ourselves to be a part.

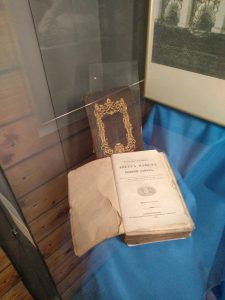

The great achievement of the Literature department is the authoritative and prize-winning twenty-volume scholarly edition of the collected works of the famous nineteenth-century poet Vasily Zhukovsky, many of whose papers are held here.

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country.

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country.

One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

I have no answer for this, except to say that maybe we can be looking more critically at what it is we pay for when we pay for all that education. And of course, to agitate for change (see above about our children out there on the public square doing the heavy lifting). There are other conversations to have, too, about economic disparities, about political and economic corruption, about corporations, about the nightmare of educational reform. Don’t look now, but the Russian national education bureaucrats have introduced a national multiple-guess assessment test that is administered to graduating seniors, the EG, that is torturing everyone in the system–teachers, parents, and students–except for the educational policy makers who BORROWED IT FROM THE UNITED STATES, who are taking great pride in their innovation, because it enables them to quantify everything. I repeat, there is real suffering going on here. My sympathy to one and all.

Where were we?

Well, we could check in with our ongoing theme of

geographical fuzziness. Your town might be located on a border (Kazan, Ekaterinburg), or it might be located in the center of the universe. It seems that Tomsk, is the center of the universe, or at least the Euro-Asian continent. But come on, let’s call it the center of the universe, a place where we all find ourselves at key moments in our lives.

There is much more to tell about Tomsk, the center of our universe at the moment, and much of it overflows the banks of what this blog can hold. But there does have to be a trip to the Tomsk NKVD Prison Museum. Let us postpone this until tomorrow.

First let us take a quick break to draw energy from the Tomsk Tatyana, patron saint of all those who study.

Some cool websites about Chekhov and Tomsk:

https://elib.tomsk.ru/page/819/

photos of old Tomsk:

http://rgo-sib.ru/photo/106.htm

His itinerary:

http://chekhov.libsakh.ru/poezdka-ap-chekhova-na-sakhalin/marshrutom-pisatelja/

The notorious letter from Tomsk: http://chehov-lit.ru/chehov/letters/1890-1892/letter-820.htm

What I found extraordinary in the museum was the abundance of individual stories that it manages to tell, even as it presents the Gulag’s physical geography, its facts, dates, and statistics. Behind each fact and number lies a human tragedy, families torn apart, individuals tortured and murdered, children orphaned. One scary exhibit is a document (one of many) listing quotas of arrests that were assigned to each region. We know this; people were arrested not necessarily for any particular crime, but to meet NKVD quotas. During the height of the Terror, those administrators whose job it was to arrest, interrogate, and sentence people feared for their own lives. In one document a local official writes to Stalin asking for his quota to be raised by a few hundred or thousand–I don’t remember–in the hopes that his zeal in rooting out enemies will spare him from being arrested and shot himself. In Stalin’s handwriting, the official’s request is “approved.” And as a result, several hundred more people were arrested and executed–and probably, in due time, the desperate man who wrote this particular appeal.

What I found extraordinary in the museum was the abundance of individual stories that it manages to tell, even as it presents the Gulag’s physical geography, its facts, dates, and statistics. Behind each fact and number lies a human tragedy, families torn apart, individuals tortured and murdered, children orphaned. One scary exhibit is a document (one of many) listing quotas of arrests that were assigned to each region. We know this; people were arrested not necessarily for any particular crime, but to meet NKVD quotas. During the height of the Terror, those administrators whose job it was to arrest, interrogate, and sentence people feared for their own lives. In one document a local official writes to Stalin asking for his quota to be raised by a few hundred or thousand–I don’t remember–in the hopes that his zeal in rooting out enemies will spare him from being arrested and shot himself. In Stalin’s handwriting, the official’s request is “approved.” And as a result, several hundred more people were arrested and executed–and probably, in due time, the desperate man who wrote this particular appeal.

The Tom River

The Tom River

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk.

fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk. the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

,

,

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country.

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country. One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

,

,

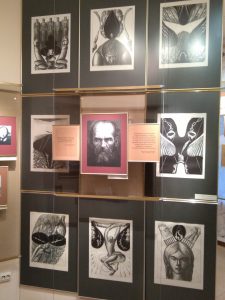

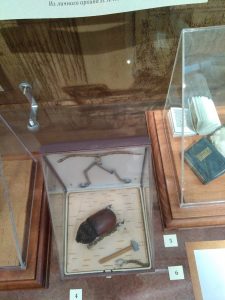

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

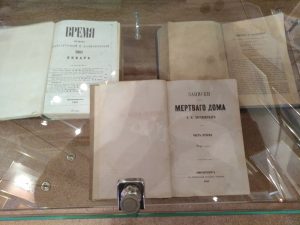

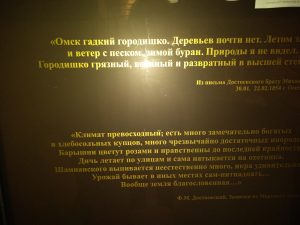

In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

bizarre accident version– scornfully dismissed by my minder in Uglich–according to which little Dmitry was stricken by an epileptic fit and fell upon his dagger, slitting his own throat. In any case, the bell was arrested and, with some effort, for it was heavy, exiled here for a few centuries.

bizarre accident version– scornfully dismissed by my minder in Uglich–according to which little Dmitry was stricken by an epileptic fit and fell upon his dagger, slitting his own throat. In any case, the bell was arrested and, with some effort, for it was heavy, exiled here for a few centuries.

which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to

which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

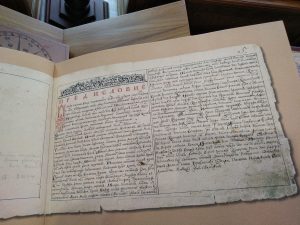

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.