In Ekaterinberg my guide is the knowledgeable, kind, solicitous, proud city citizen, specialist in 19th-century Russian literature and an expert on Reshetnikov (and of course Chekhov), Alexander Kubasov.

Ekaterinberg, the fourth largest city in Russia, is made of rocks and iron, a tough, hard place with a short but riveting and gruesome history. Its youth (dating from 1723 or so) makes for quite a jolt from Kazan. The (original) point of the city was to dig into the hills, I mean the mountains, extract the riches within, and produce big, powerful things for European Russia. Always mighty and muscular, it came into its own during Stalin’s push for industrialization in the 1930s, and was a major production center of military equipment for the Soviet Union during World War II.

During the Soviet years the city was renamed Sverdlov to honor one of the masterminds of the Bolshevik revolution who died early, of illness, before he could suffer a worse fate, like what awaited many of the “Old Bolsheviks.” Тhis early death also prevented Sverdlov from being involved in later acts of murder and mass terror, and possibly has allowed his name to remain in many places where others’ names have been removed. And unlike Moscow and St. Petersburg, the city retains monuments and street names from the Soviet period, such as Lenin, Marx, Dzerzhinsky, 1905 Square. While I have you, let me sneak in a little street-corner photo from Tobolsk, a place that technically we have not visited yet, but hey…

Speaking of the NKVD, quite by surprise, on a solitary walk I ended up in the former compound where officials lived and played. My original purpose was to visit a branch of the regional history ethnography museum to see the Shagirsky idol (see below, under “The Problem With Numbers”), but learned from the ever-solicitous muzeishicki that their museum occupied the Cheka residential complex. The staircase is a feature of particular pride.

…

…

The house recalls the Moscow “House of Government,” featured in Yuri Slezkine’s monumental new history of the Bolsheviks, which I assigned to myself before coming on this trip. It tells the story of the grand House on the Embankment across from the Kremlin in Moscow, where all the big officials lived….This is kind of the same concept, but out here in Ekaterinburg.

There is a nagging thought here, of course, under all this beauty, one that recalls Dostoevsky. In Dostoevsky’s novels you should always be suspicious of well-dressed, fragrant people (Luzhin, for example). The external glamour usually marks a bottomless cesspit of evil within. We will return to this theme when we visit the Stalin terror memorial park.

In the meantime, though, Alexander takes me to the art museum. Rodina, Russia, will not attack, but she stands firm, ready to defend.

And seek in vain for any mold lines on these beautiful animals.

Behold the Kasli Pavilion, a UNESCO world treasure, where you will see what can result when man puts hand to iron. The pavillion was shipped off to the Paris World Exhibition in where it slam-dunked the Grand Prix and sent everyone else slinking home with their tails between their legs.

The overriding impression here is beauty and craft. I am teleported into Nikolai Leskov’s 1881 masterpiece, “Lefty,” (Левша) about how the Tula masters shod the tiny steel flea…

The city’s metallic identity extends to the fine art of Mezzo Tinto printmaking, in which the artist scratches designs onto metal plates. The process, unlike forms of etching, uses no chemicals, just meticulous hand craft. Ekaterinberg hosts an international festival at the museum, featuring masters like Art Werger.

Ekaterinberg cares about culture; there’s a museum on every corner…

Wait, but What About Chekhov?

Chekhov stopped for a few days in Ekaterinburg on his way to Sakhalin in the spring of 1890. The hotel where he stayed is conveniently called The American, and it still stands.

it’s the building on the left in the foreground.

What Chekhov did in Ekaterinburg is clouded in mystery. But it is good to have a sighting. Quick reminder here: I’m not traveling with a professional photographer or in fact, blog editor, translator, or trip planner.

What Chekhov did in Ekaterinburg is clouded in mystery. But it is good to have a sighting. Quick reminder here: I’m not traveling with a professional photographer or in fact, blog editor, translator, or trip planner.

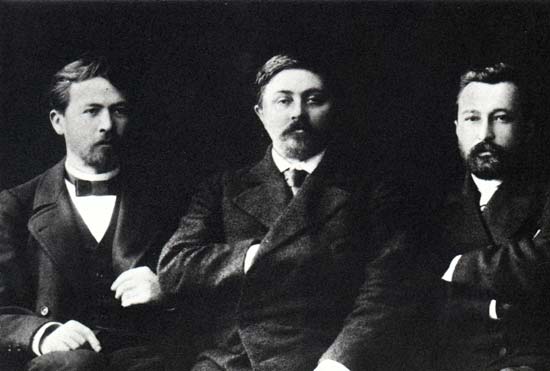

There’s a literary district near the center of town; Chekhov might have visited the house of Ekaterinburg writer Dmitry Mamin-Siberiak in these parts. There’s a famous photo of them together with, on the right, Ignaty Potapenko (a prose writer famous and much read during his time, but now perhaps even more famous for the role he played in providing, through his scandalous behavior with Chekhov’s on-again, off-again girlfriend Lika Mizinova, the central episode and other key elements (character, quotes…) for his play The Seagull). Maybe Chekhov visited here! Of course he must have.

We are on Chekhov’s trail; he has brought us here. But inevitably we are getting distracted–and why not? Personally, I think that getting distracted is one of the main points of living, though there’s always the possibility that your boss may not agree.

The Border

So first, geography, and we could linger here for a long time. Ekaterinburg lies on the border between Europe and Asia. Where is that exactly? Someone–actually geographer Philip Johan Von Strahlenberg, drew a line down the Ural hills, I mean mountains, in the 18th century, and here’s your Europe and Asia.

The Problem With Numbers

Personally, I just love this. He just drew a line…It reminds me of the atlases in the Kazan University Library. Why do we really need something precise, to the thousanth-place longitude and latitude? And while I’m at it, let’s ask the same thing about seconds, minutes, years, and milleniuma.

Probably because it gives you something to hold onto when you see something like this, which was dug out of a peat bog in the late 19th century and turns out to be, oh, 10,000 years old–The Great Shigir Idol.

Given how momentous this all is, the place is remarkably unfussy, though those of us who have spent time elsewhere in Asia will not be surprised to see the coin-bashing station and the wish ribbons.

The “two coffees for the price of two” sign has a Russian aura to it.

I do not judge. I am in, hook, line and sinker.

From Ekaterinburg Chekhov writes to his fiend the doctor Obolonsky: “I’m sitting now in Ekaterinburg; my right leg is in Europe, the left in Asia. The weather, to put it mildly, is disgusting…

I guess Chekhov was turned the other way.

The Terror

Travel down the road a bit, though, and the music is in a minor key. The Great Terror did not pass Ekaterinburg, I mean Sverdlov, I mean Ekaterinburg, by. Here in a field by the highway is the Memorial to the Victims of Political Repressions, 1930s-1950s. Ernst Neizvestny made the memorial sculpture.

There are mounds of mass burials, and long walls listing the names, with the life span years noted, all of them that I saw, creepily, ending in 1937 or 1938. This is also the burial place of a host of the finest officers in the Red Army, shot here, and now memorialized in a white tree plaque.

The scope of the insanity and brutality is incomprehensible. It shadows over every detail of this city. Again I think, heaviness and fragility, stone and flesh.

Speaking of which…

Here looms the Church on the Blood. There are three Churches on the Blood in Russia: they commemorate the violent death of members of the Imperial family. I have now seen all of them this summer: Dmitry’s church in Uglich, Alexander II’s in St. Petersburg, and now this one, the most horrifying of them all. Tsar Nicholas II, Alexandra, and their five children were taken from their holding place in Tobolsk in the summer of 1918, brought to the Epatiev House here, and shot, all of them, in the basement. Boris Yeltsin, during his time here, had the house torn down. The Church on the Blood stands on the spot.

Yeltsin’s Town

A smart move, I say to combine what we would call the Presidential Museum (or Library?), with a high-end shopping mall with great food. it is truly one of the great museums, I’d say. A vivid short course in the whole sweep of Russian history, interactive exhibits–it’s excellent for those of us with a short attention span and a full agenda, and before you know it, you’ve spent the whole day.

I particularly enjoyed the bus. The front window shows a video about Yeltsin’s life, and the side windows show street scenes. Public transit was one of Yeltsin’s focuses as a city official. You will sit in the second seat from the front on the right. A small boy enters the bus and does exactly what you would have done if you were a small boy, which kind of drowns out the audio–but by now you have an excellent sense of the Yeltsin years.

A Quick Note about Beer

OK, now I know that no one in their right mind comes to Russia for the beer. I also get that Sunday night is not when the varsity bartenders are on duty. And I know that Guiness (this is Guiness despite what it says on the class) is supposed to foam up. And maybe they think that females (or old people, or professors, or Americans, or whoever) shouldn’t be drinking beer. But honestly, is this the best they can do?

OK, now I know that no one in their right mind comes to Russia for the beer. I also get that Sunday night is not when the varsity bartenders are on duty. And I know that Guiness (this is Guiness despite what it says on the class) is supposed to foam up. And maybe they think that females (or old people, or professors, or Americans, or whoever) shouldn’t be drinking beer. But honestly, is this the best they can do?

A New Friend

To recover from all the stimuli from my walks and drives around Ekaterinburg, I visited the Nature Museum, and found the love of my life:

Unfortunately, I was swooning and neglected to write down this charming fellow’s name.

Could the love of your life just be an Arctic Fox with really bad taxidermy?